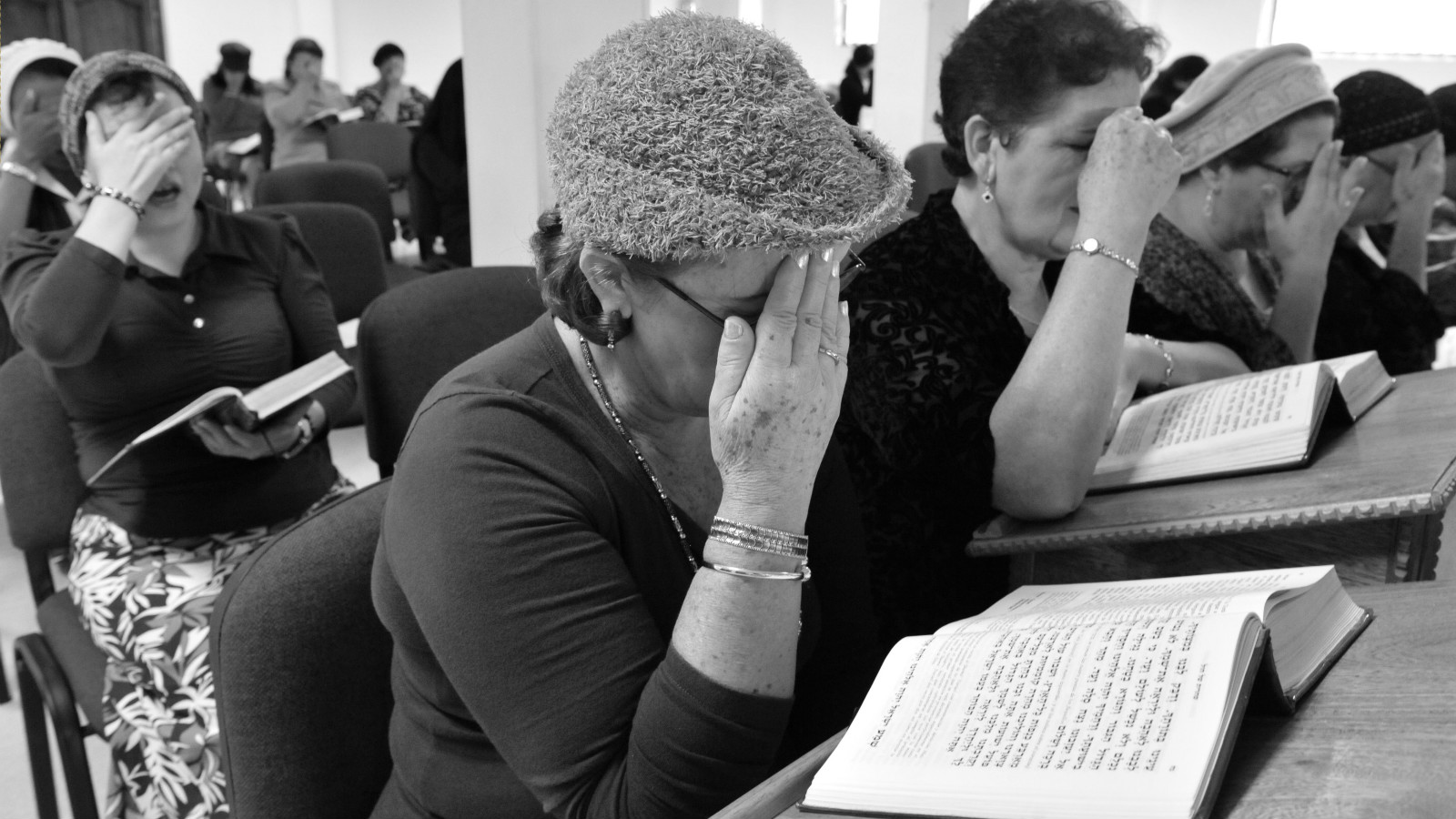

“Judaism is about how to live, not just what to believe,” writes one contemporary observer. Jewish daily life and practice is how Jews do things–day in and day out, and week after week–that embody the ideals and standards expressed in Judaism’s sacred writings and its ancient (and modern) traditions.

Holiness

The children of Israel are called upon in Leviticus 18:2 to be holy: You shall be holy, for I, the Lord your God, am holy. Holiness–kedushah–is a theological concept. It refers to the attempt to live in a way that emulates or brings us into contact with the realm of the divine, a realm of existence beyond that which is objective and verifiable. Living a life of kedushah, though, is a practical matter. It means identifying ideals in alignment with divinity and generating codes of behavior that bring us into harmony with those ideals. Jewish thinkers have offered suggestions of how to accomplish this, often taking us beyond the letter of Jewish law.

Ethical behavior

The principles of ethical behavior elaborated by Jewish thinkers usually begin with assumptions about God and about God’s expectations of Jews or generally of human beings. That makes it difficult to separate ethical behavior from the quest for holiness of which it is a part. Nonetheless, the Jewish literary tradition provides us with a number of works that explore the underlying principles of ethics and offer detailed explorations of interpersonal ethics.

Mitzvot (Commandments)

Traditionally, Judaism has attempted to codify behavioral norms on the basis of specified requirements and prohibitions that govern the ethical and the ritual alike. They seem to generate a total guide to existence, regulating a person’s relations both with God and with other human beings. The ancient rabbis derived some of these directly from the Torah–or at least found support for them there. Others are unabashedly rabbinic innovations. Whether designed to safeguard the biblical limits by placing additional restrictions on Jews’ behavior, or responding to exigencies not addressed by the Torah, those innovations derive their authority from the Jewish community’s acceptance of rabbinic authority. Philosophers and theologians have debated whether some underlying principal or ethic beyond the mitzvot themselves gives shape to them. Contemporary Jews differ over whether the system of mitzvot should be taken as obligatory or as a source of values for independent, individual decision-making.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.