Commentary on Parashat Vayeshev, Genesis 37:1-40:23

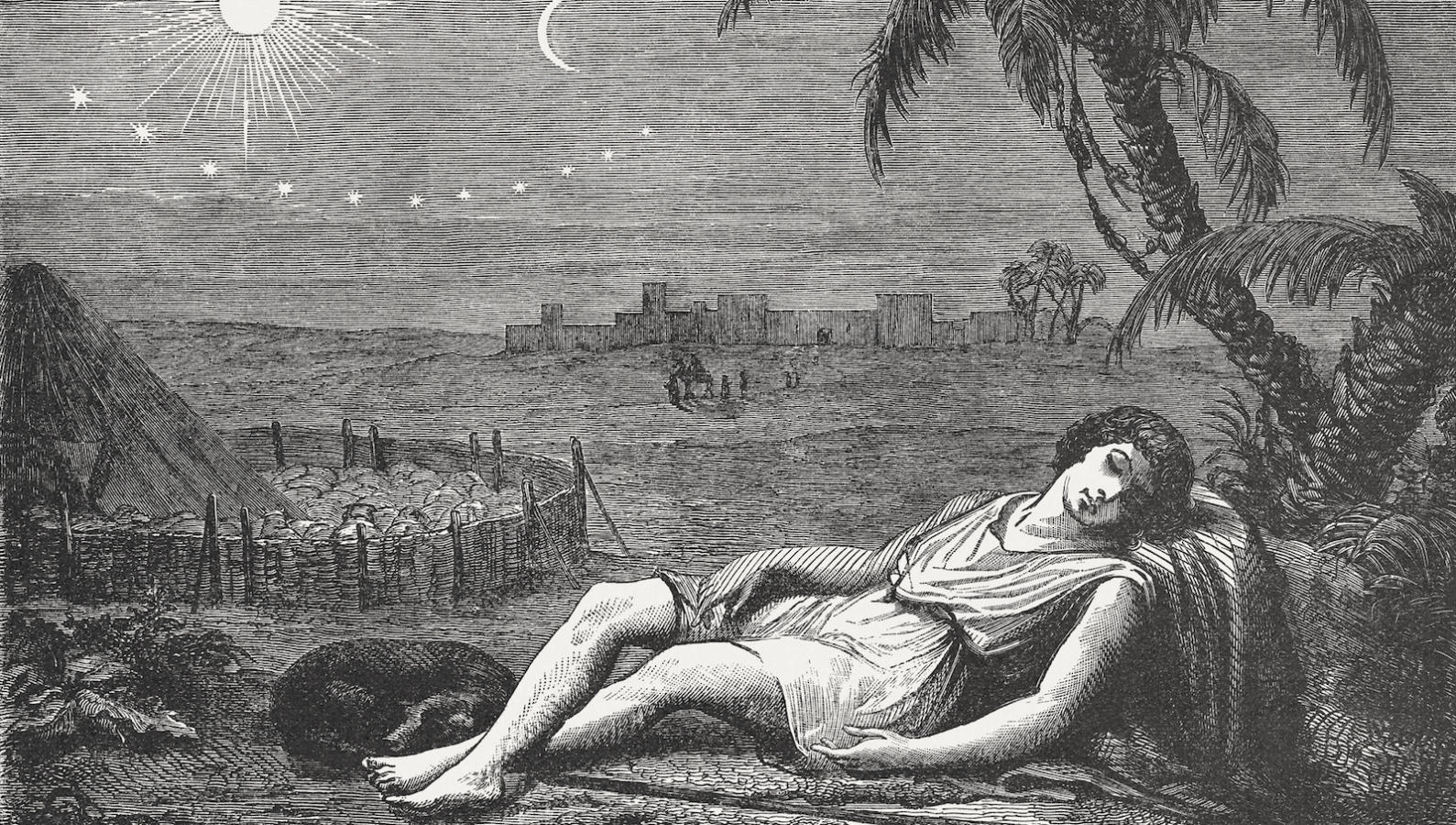

The made-for-stage story of Joseph begins with this week’s portion, Vayeshev, and will continue for the next four weeks until the end of the book of Genesis.

From the outset of the portion it is clear that Jacob favors Joseph among his 10 sons, giving him the infamous “ktonet pasim,” the coat of many colors, or ornamented tunic. This preferential treatment, as well as Joseph’s penchant for sharing egocentric dreams, angers his brothers. The brothers react harshly, selling poor Joseph into Egyptian slavery. In Egypt, Joseph demonstrates surprisingly strong character by resisting the lurid designs of his boss’s wife.

2 …At 17 years of age, Joseph tended the flocks with his brothers, as a helper to the sons of his father’s wives Bilhah and Zilpah. And Joseph brought bad reports of them to their father. 3. Now Israel loved Joseph best of all his sons, for he was the child of his old age; and he had made him an ornamented tunic. 4. And when his brothers saw that their father loved him more than any of his brothers, they hated him so that they could not speak a friendly word to him. 5. Once Joseph had a dream which he told to his brothers; and they hated him even more. 6. He said to them, “Hear this dream which I have dreamed: 7. There we were binding sheaves in the field, when suddenly my sheaf stood up and remained upright; then your sheaves gathered around and bowed low to my sheaf.” 8. His brothers answered, “Do you mean to reign over us? Do you mean to rule over us?” And they hated him even more for his talk about his dreams. 9. He dreamed another dream and told it to his brothers, saying, “Look, I have had another dream: And this time, the sun, the moon, and eleven stars were bowing down to me.” 10. And when he told it to his father and brothers, his father berated him. “What,” he said to him, “is this dream that you have dreamed? Are we to come, I and your mother and your brothers, and bow low to you to the ground?” 11. So his brothers were wrought up at him, and his father kept the matter in mind.

Parshanut/Commentaries

Jewish tradition has much to say about the causes of enmity against Joseph. Even traditional rabbinic commentators are troubled by the young man’s behavior. Some authorities claim that the act of dreaming the dreams itself was reprehensible, as it exhibited visions of grandeur that Joseph obviously nursed during wakeful moments. The commentators understand the brothers’ hatred of Joseph and express shock that he would reveal not just one but two dreams.

Why, then, does Jewish tradition refer to Joseph as “HaTzadik,” some commentators ask? Such “overweening pride and self-importance [seems] remote indeed from the conception of righteousness implicit in the title,” writes contemporary scholar Nehama Liebowitz. Elie Wiesel does battle with this notion as well, asserting that Joseph was the singular ancestor called “righteous” in a line of great patriarchs.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Countless traditional commentators offer that Joseph’s greatest act as tzadik came in resisting the temptation of Potiphar’s wife. He was also said to be consistently God-fearing in a secular world, and humble in a position of power.

But Wiesel is not satisfied. The Nobel laureate knows from later Torah portions that even while Joseph was praising God’s divine wisdom, he was endlessly scheming his own next move; while he embraced his Abrahamic origins, he kept one foot firmly planted in the secular, Egyptian culture that rewarded him.

A Word

The Joseph saga raises the question of how contemporary Jews choose their biblical role models. What can we learn from these eminent characters with all their internal flaws, their morally imperfect behavior, their all-too-human shortcomings?

There is a fine line between being righteous and being self-righteous. In Hebrew, the distinction is between being a “tzadik,” righteous, and being “tzadik b’einav,” righteous in one’s own eyes. Joseph, it seems, struggled with his own divinely ordained charm, which was both the source of his brothers’ enmity and of his effectiveness as a member of Pharaoh’s court.

Wiesel only accepts Joseph as “HaTzadik” because it is a righteous person who resists temptations in human relationships. Joseph is crowned tzadik because he ultimately forgave his brothers for selling him into slavery and compassionately helps his family move to Egypt during a time of famine in Canaan. Joseph succeeds in vanquishing his bitterness and turns it into love. “What does all this mean?” Wiesel asks. “That one is not born a Tzadik; one must strive to become one. And having become a Tzadik, one must strive to remain one.”

Provided by Hillel’s Joseph Meyerhoff Center for Jewish Learning, which creates educational resources for Jewish organizations on college campuses.