Reprinted with permission from JPS Guide: The Jewish Bible.

Basic justice was administered by the local court of elders sitting at the city gate, while more difficult cases came be fore the king (I Kings 3:16-28). Moses is said to have set up a hierarchical system of courts in the desert (Exod. 18:1 3- 26 ), and King Jehoshaphat is credited with appointing royal judges in the cities of Judah (2 Chron. 19:5).

o Property law deals with the ancestral estate. On the father’s death, his sons divided the land into equal shares, the firstborn taking a double share. If one of the sons died childless before there was a division of the estate, either because the father was still alive or because after the father’s death the brothers had continued to hold the land in a kind of partnership (“brothers dwelling together”), levirate law applied: the surviving brother had to marry the deceased’s widow, and their offspring would take the place of the deceased, thereby preserving his share of the inheritance (Deut. 25:5-10).

o If a man died leaving daughters but no sons, the daughters were allowed to inherit the family’s estate (Num. 27: 1-1I1, 36:1-12).

o Various laws protected the family’s ownership of their land. If poverty forced the owner to sell, he or a kinsman could redeem the land and thus bring it back into the family (Lev. 25:25-27). If redemption were not possible, the land would automatically return to its owner at the Jubilee, which occurred every 50 years (Lev. 25:28).

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

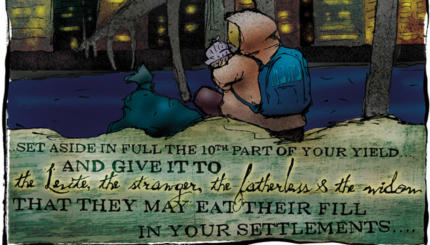

o A person cultivating land bore social responsibilities. He had to set aside part of his crop for the poor and needy (Lev. 19:9-10; Deut. 24:19-2 1) and every 7th and 50th year leave his land fallow so that its produce could feed those in need (Exod. 23:10-11; Lev. 25:3-7).

o The law made great efforts to alleviate debts. Interest was forbidden on loans to fellow-Israelites (Exod. 22:24). Although a creditor was entitled to foreclose a debtor’s possessions, or even his family (2 Kings 1:1), certain items (such as a millstone) could not be taken in payment of debts (Deut. 24:6). Impoverished kinsmen, like land, could be redeemed (Lev. 25:47-53) and slaves could be set free automatically after a number of years’ service (Exod. 21:1; Lev. 25 :54; Deut. 15:12). It has often been suggested that such laws were merely utopian. In fact, it was common practice for the kings of the ancient Near East to declare a cancellation of debts and consequently emancipate slaves and land. This was regarded as one of the king’s duties, although the timing was left to his discretion. The difference in the biblical law is its replacement of the king’s role by an automatic cycle of 7 or 50 years, which would ensure the enforcement of these reform measures. King Zedekiah actually declared a freeing of slaves, but subsequently the officials and the people forced them in to slavery again (Jer, 34:8-11).

o Marriage was an alliance between families in which the bride was the object of the transaction. The first phase was an agreement between the groom (or his father) and the bride’s father, who could demand a payment known as mohar for the hand of his daughter (Exod. 22:15-16). Payment would normally be in money, but could, as in the case of Jacob, be in services (Gen . 29). Once the mohar was paid, the girl was betrothed, and although the marriage was not yet consummated, the law already regarded her as married (Deut. 22:23-29). Divorce could be initiated by the husband alone. A special provision ruled that a wife, once divorced and remarried, could not return to her first husband if her second marriage ended (Deut, 24:1-4).

o Polygamy was permitted, but it was forbidden to marry two sisters (Lev. 18:18). This had apparently not been the case in the time of the Patriarchs, for Jacob married Laban’s two daughters, Leah and Rachel (Gen. 29).

The leading motifs of early biblical literature–election, redemption, covenant, and law-are closely interconnected: God elected the Children of Israel to be God’s treasured possession. God’s redemptive intervention into history liberated an enslaved people who became bound to God through a pact whose stipulations demand the utmost obedience. The continued existence of this religion s community, according to the Bible, completely depends on the observance and performance of those principles and injunctions that constitute the charter of its covenant with God. The will of God ex pressed through law is the basis of the covenantal relationship between God and the nation of Israel.