Over the centuries, many customs have sprung up to enhance the way in which we enter , the final day of this season. Some of these customs, such as flogging oneself to atone for sin, happily have been forgotten. Others, such as immersion in a mikvah to indicate a state of purity, are still practiced by some. The most well‑known and yet most controversial of these customs is the practice of Kaparot, which literally means “atonements,” but in the sense of “ransom.”

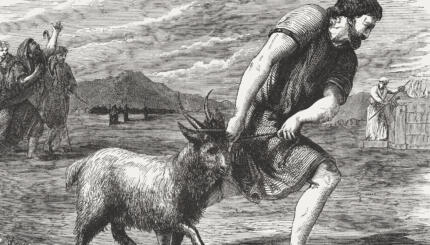

Traditionally, a rooster is swung around one’s head and is then slaughtered while being declared a “substitute” for the individual, as an atonement for his or her sins. Like the Tashlikh ceremony of , Kaparot is a folk ceremony that may have had superstitious, pagan origins. Rabbinic opposition to Kaparot has been strong and remains so today.

Some lived in deepest darkness, bound in cruel irons … (Psalms 107:10).

He brought them out of deepest darkness, broke their bonds asunder … (Psalms 107:14).

There were fools who suffered for their sinful way, and for their iniquities. All food was loathsome to them: They reached the gates of death. In their adversity they cried to the Lord and He saved them from their troubles. He gave an order and healed them; He delivered them from the pits. Let them praise the Lord for His steadfast love, His wondrous deeds for mankind (Psalms 107:17‑21).

These verses are followed by an additional excerpt from the Book of Job:

Then He has mercy on him and decreed, “Redeem him from descending to the Pit, For I have obtained his ransom” (Job 33:24).

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

To this is added the words: Life for life.

Prayers are then recited, indicating the function of the rooster as a substitute for the individual. The rooster is twirled three times around the head of each man; a hen is used for women. Both birds are then slaughtered and given to the poor. Some people have substituted money, in this ceremony, for the rooster or hen.

One need not go as far as those scholars who see the Kaparot as originating in an offering to Satan in order to understand the many objections to this ritual. Kaparot follows the pattern of the scapegoat, a ritual of riddance, but comes too close to superstition in indicating that one may substitute the death of an animal for one’s own life. Among those who objected to the ceremony were the 13th‑century Moses ben Nahman (the Ramban) and the 16th‑century Rabbi Joseph Karo, who wrote in his great work the Shulchan Arukh: “The custom of Kaparot … is a practice that ought to be prevented.” Needless to say, the objections of great authorities were not sufficient to prevent this ritual from becoming an accepted custom among the people.

Excerpted with permission from Entering the High Holy Days (Jewish Publication Society).