Among the most exciting “new” developments in modern Jewish music has been the late 20th-century rediscovery of klezmer, folk music of the itinerant European Jewish musicians that traveled with them on their journey to the New World. As with Yiddish theater and other aspects of culture dependent upon links to the “old country,” klezmer’s popularity faded with the cessation of massive immigration from Eastern Europe and the increasing socialization — and assimilation — of America’s Jews.

Learn more about the history of klezmer music here.

By the late 1960s, klezmer had become a distant memory, a relic of another era, stored on 78 RPM recordings in attics and basements of Jewish homes but replaced at weddings and other communal functions by the music of Israel and popular American repertoire. The children of the aging klezmorim [klezmer musicians] turned to American dance bands, classical music or, ironically, the folk repertory of America’s other ethnic communities. Young Jews flocked to Irish music, jazz and American folk song.

Simple Question Leads to Klezmer Revival

But in 1973, while exploring the string band music of Appalachia, Henry Sapoznik was asked whether Jews had their own music. With this simple question, this son of a European-born cantor, a deliberate refugee from the Jewish music of his Lubavitch yeshiva [school] and the Catskill hotels where his family spent Passover vacations, now turned back to his own traditions. Beginning with a cache of old records at New York’s YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Sapoznik unearthed the vestiges of European klezmer music, already reinterpreted and transformed by American recording technology.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Sapoznik’s enthusiasm for his own music, which he saw now with different eyes, led him to additional research into klezmer music, funded by U.S. government grants. He met elderly Jews who had played in the klezmer ensembles of the 1920s and on some of the first klezmer recordings by companies like Columbia and RCA Victor. By 1979, Sapoznik had formed Kapelye to play a concert in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1981 the group, enhanced by clarinetist Andy Statman, Sapoznik’s own cantor father, and others, formed Der Yiddisher Caravan, a national touring show that performed cantorial selections, Yiddish theater songs, and klezmer music in concert venues across the United States. Coincidentally, others had also begun to delve into klezmer music.

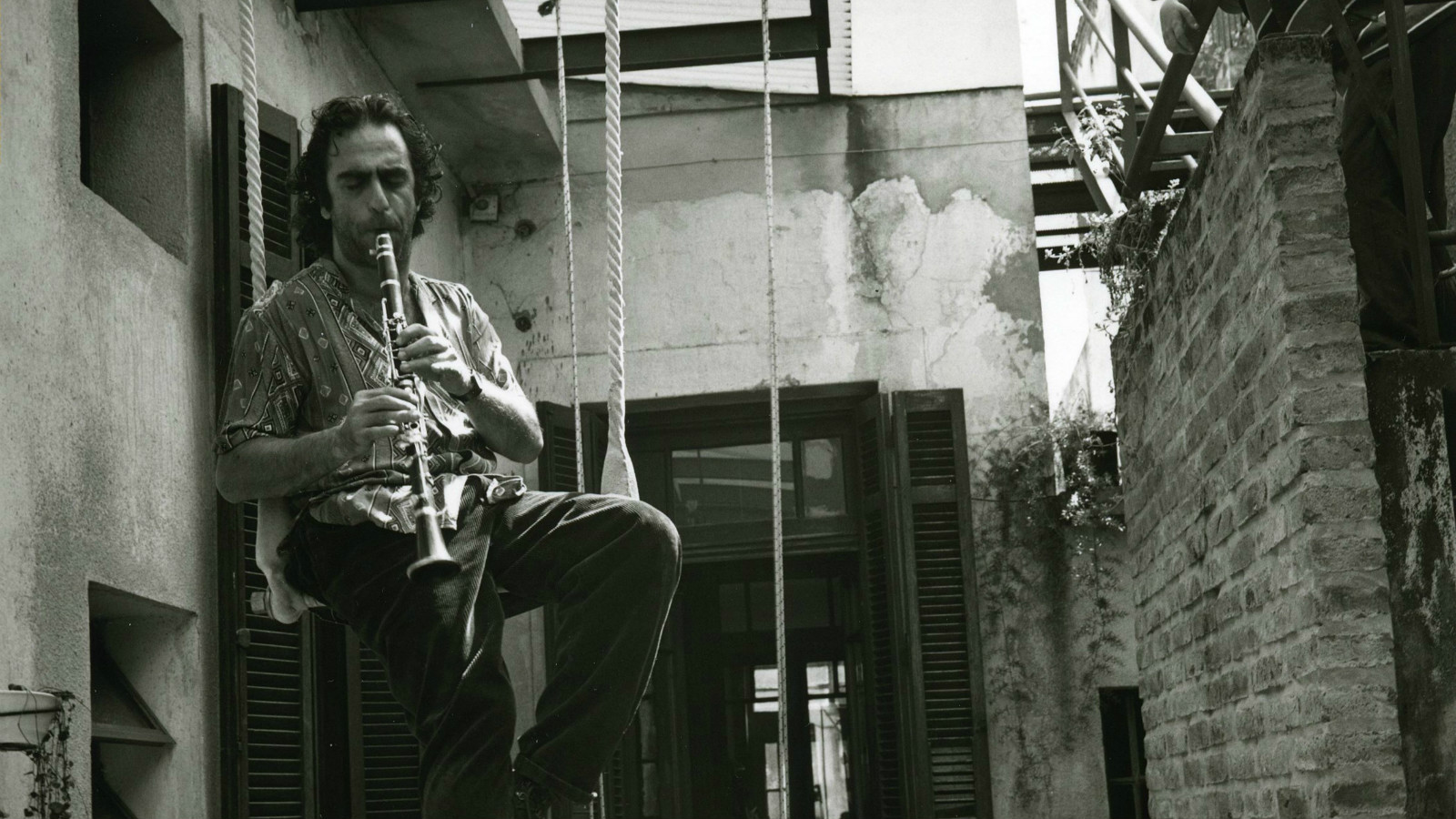

Clarinetist Giora Feidman, formerly of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, popularized klezmer in Israel and in appearances in America. Andy Statman and ethnomusicologist Zev Feldman had staged a retrospective of the work of veteran European-American klezmer musician Dave Tarras (1897-1989) in 1978. Hankus Netsky, a jazz music instructor at the New England Conservatory of Music, had rediscovered the klezmer music of his trumpeter uncle Sol Katz in a Philadelphia basement. Netsky enthusiastically recreated the big band sound of the early American klezmer recordings with his students and colleagues, forming the Klezmer Conservatory Band.

The rebirth of klezmer continued on an upward trajectory of isolated but increasingly important events involving Henry Sapoznik and his growing network of colleagues. Sapoznik’s research resulted in Folkways Music’s retrospective reissue of some classic 78 RPM recordings, Klezmer Music: 1910-1942.

In 1982, Sapoznik became the director of the Max and Frieda Weinstein Archives of Sound Recording at YIVO. That summer, his band Kapelye appeared in the Hollywood version of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen and issued their first album. In 1983 Sapoznik and Andy Statman were joined by Pete Sokolow and other top New York Jewish and jazz musicians, performing their show Klezmer Meets Jazz at New York’s Jewish Museum and at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater. Pete Sokolow used the arrangements he wrote for that show to form his Original Klezmer Jazz Band, which issued its first recording in 1984, the same year in which a group calling itself The Klezmorim played Carnegie Hall and the Klezmer Conservatory Band scored a huge success appearing on Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion, broadcast on National Public Radio stations across the country.

Back to Europe

Kapelye became the first klezmer band to tour Europe, appearing in Britain, France, Switzerland, Belgium, and Germany (playing one of its best-received concerts in a Berlin mansion that had been used as a Gestapo headquarters during the Second World War). Klezmer had returned to its roots, completing a cycle and launching a rebirth whose popularity in Europe continues unabated–though largely among non-Jewish audiences and with newly formed bands including or entirely comprised of non-Jewish players.

Meanwhile, across America, klezmer bands flourished wherever there were Jews: in Chicago and Philadelphia and San Francisco; but also in Boulder, Colorado; Montpelier, Vermont; and New Orleans, Louisiana. Klezmer appealed to a wide cross-section of audiences: gray-haired grandparents who remembered the klezmer bands of their distant youth; their grandchildren for whom Yiddish culture had no special appeal; and the friends of those grandchildren who came from the ethnic communities in whose music the Jewish musicians of the 1960s had once sought refuge, and who now welcomed a reborn tradition into their midst.

Klezmer as an Amalgamation of Cultures

From its inception in Europe, klezmer had always reflected a unique amalgamation of the music of the Jewish community with the music of the surrounding culture. Klezmorim playing at Jewish celebrations and at non-Jewish festivities alike had contributed to a cross-pollination between Jewish and gentile cultures, enriching both. Like the community, which eagerly embraced the potential of any melody to bring greater glory to the Creator, klezmer musicians adapted a wide variety of tunes to serve their purposes. This exchange continued in America, with Jewish musicians borrowing jazz and other styles, and crossing over, adapting Jewish tunes to the diverse marketplace of American cultural ideas. Ziggy Elman (nee Henry Finkleman, 1914-1968) turned the “Odessa Bulgar” into the Swing Era’s “The Angels Sing,” while “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” by Sholom Secunda (1894-1974) was equally successful (on both sides of the Atlantic) as a Yiddish-language favorite and as an American pop success sung by the Andrews Sisters (albeit with English lyrics).

Klezmer music, whether in Europe or in America, at the turn of the 20th century or the 21st or the 18th, has done what Jewish music has done since it was born in the Middle East at the beginning of recorded time: It has adapted the music of the larger, surrounding culture. What it has never done, however, is assimilate completely. Rather, klezmer music in particular, and Jewish music as a whole (as the Jews who created it), consciously and subconsciously borrowed liberally but never sacrificed its Jewish sensibility. Jewish values, the internal rhythms of Jewish languages, the musical motives of the synagogue and the schoolhouse, have all enabled Jewish music to retain a unique cast that separates it from that of the surrounding community.

The contemporary era, with its technological immediacy and the shrinking of the global village, has created challenges that Jewish musical tradition never faced in previous generations. Moreover, the availability of musical notation and easy recording techniques have made possible the exchange of melodies between unlikely partners–and the near-instant incorporation of these tunes into otherwise “traditional” settings. Witnesses who know the source of such “borrowed” materials often rail at the encroachment of these foreign influences, and the conservators of Jewish music traditions ( , and Ashkenazi) author long discourses on the deterioration of their heritage and the unhappy cultural future awaiting the next generation.

But while the challenges awaiting that next generation may be unprecedented, the very factors that have precipitated this 21st-century crisis of identity have also made possible the preservation of important aspects of Jewish musical history. Ethnomusicologists have studied the sounds of Jewish musical communities around the world. Books of this music and recordings of these songs have created a permanent record of the sounds of Jewish musical tradition. As long as there are people who call themselves “Jews” there will continue to be Jewish music. While it will continue to evolve and emerge as something not quite like its past legacy, those who respect the continuity of the Jewish cultural heritage, in all its diversity, will no doubt find a way to keep it within the sounds of Jewish memory and practice–as Jews have always done.

Excerpted with permission from Discovering Jewish Music (Jewish Publication Society).