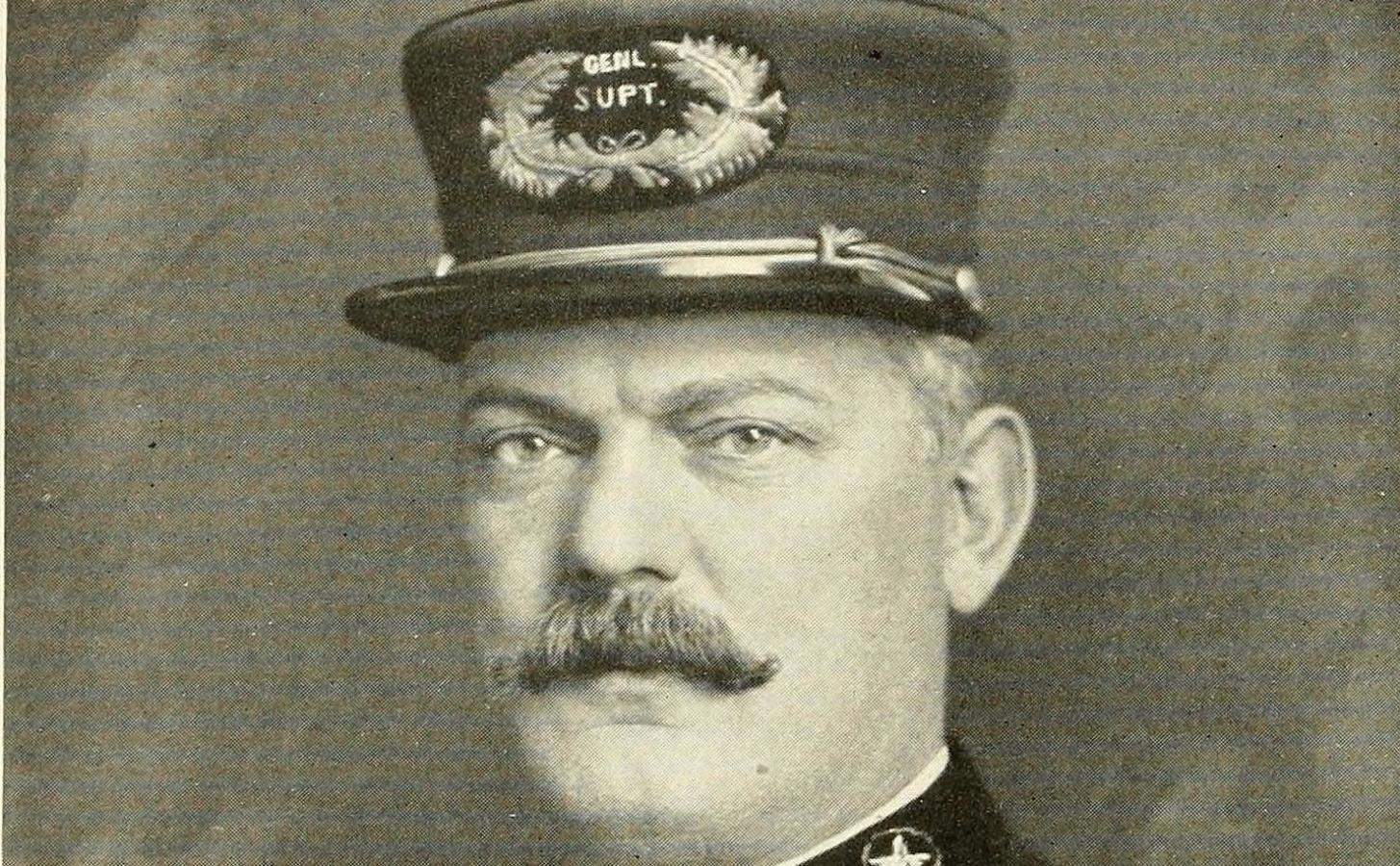

On Monday morning, March 2, 1908, Chicago Police Chief George Shippy reported that a young man, probably of Sicilian or Armenian birth, knocked on the door of his home, asked to see Shippy and was admitted by the family maid. Perceiving what he described as hatred in his visitor’s eyes, Shippy grabbed the young man by the wrists and started to search the suspect. According to Shippy, the youth squirmed free, pulled a knife from his pocket, stabbed Shippy under the right arm and then drew a revolver and shot Shippy’s son Harry, who entered upon hearing the commotion. The suspect then shot James Foley, Shippy’s bodyguard. Seeing Harry shot, Shippy pulled his own gun and shot the intruder, as did Foley. Struck by seven bullets, the youth died en route to the hospital.

Despite his wound, a few hours later Shippy wrote a widely published account of the shooting. Shippy believed the young man was an anarchist who wanted to kill him in retaliation for Shippy’s ban on “Red” Emma Goldman, the famous Jewish anarchist, whom he would not let speak publicly in Chicago. However, the dead man was not Armenian or Sicilian, but Lazarus Averbuch, a recent Jewish immigrant from Kishinev, Bessarabia.

After cursory investigations, the Chicago police and the Cook County coroner certified that Shippy was justified in killing Averbuch. In 1886 when an anarchist bomb exploded at a rally in Haymarket Square, killing two Chicago police officers, city officials effectively banned anarchist rallies. When Emma Goldman announced a speaking tour in Chicago in March of 1908, Chicago Mayor Fred Busse prohibited her from appearing. Shippy expected her anarchist supporters to retaliate. In this heated political context, few were surprised that the inquests confirmed Shippy’s invocation of self-defense.

At first, Chicago’s secular and Jewish press, and most of its Jewish leadership, accepted that Averbuch went armed to Shippy’s house, intending to kill the chief. Jewish leaders asserted that not all Jewish immigrants were affiliated with anarchism and asked the public not to tar all Jews with Averbuch’s brush. According to historians Walter Roth and Joe Kraus, most of Jewish Chicago would have been happy if the Averbuch incident would simply go away.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Not every corner of the Jewish community, however, was content with the official version of the Averbuch saga. The socialist press, Emma Goldman and her followers, and Hull House founder Jane Addams each found too many inconsistencies in Shippy’s story. Funded quietly by Chicago’s leading Jewish communal figures, particularly Julius Rosenwald, the head of Sears, Roebuck, Addams organized a private investigation of the case. Led by young Chicago attorney Harold Ickes, who later served as secretary of the interior under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the investigation surfaced contradictions and absurdities in Shippy’s account.

Ickes represented Averbuch’s interests — and those of the Jewish community — at the coroner’s inquest. Averbuch’s sister, Olga, the only person who knew Averbuch well, was the only witness of Averbuch’s behalf. She told the panel that her brother never had anarchist leanings or contacts, that he never owned a gun or knew how to shoot one and that she had no idea why he went to Shippy’s house. She pleaded for justice and for a Jewish funeral for her brother, who had been buried secularly in Chicago’s potter’s field. The inquest exonerated Shippy, but Olga’s character left the impression that there was more to the story than Shippy’s version told.

Chicago’s Jewish press began to argue effectively that Averbuch was the innocent victim of Shippy’s overreaction. The city’s Jewish Courier hypothesized that as a recent immigrant from Kishinev who was seeking work, perhaps in California or Iowa, Averbuch went to Shippy’s house to obtain a letter of good character from the chief, such as he would have needed in Russia. According to this theory, Shippy panicked when he saw Averbuch, reached for his service revolver and fired several shots at the young man. One of Shippy’s wild gunshots probably struck his son Harry as he entered the room. Shippy’s aide, Foley, fired at and struck Averbuch as Shippy’s errant bullets wounded Foley. If this version of events is accurate, Averbuch was the innocent victim of Chicago’s — and America’s — anti-immigrant, anti-radical hysteria. While the coroner’s inquest exonerated Shippy, Chicago’s Jewish press tried to call him to account.

In the end, neither Ickes nor the Jewish press changed the majority perception that Averbuch was an anarchist and that Chief Shippy killed him in self-defense. Shippy never returned to active duty after his wounding, and resigned from his post two months later. He died in 1911, deranged from syphilis. Lazarus Averbuch, after being disinterred from potter’s field and re-autopsied for the inquest, was reburied in an unmarked grave in a Jewish cemetery. The Averbuch case was dropped. A heartbroken Olga Averbuch returned to Europe four years later and was almost certainly killed in the Holocaust.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.