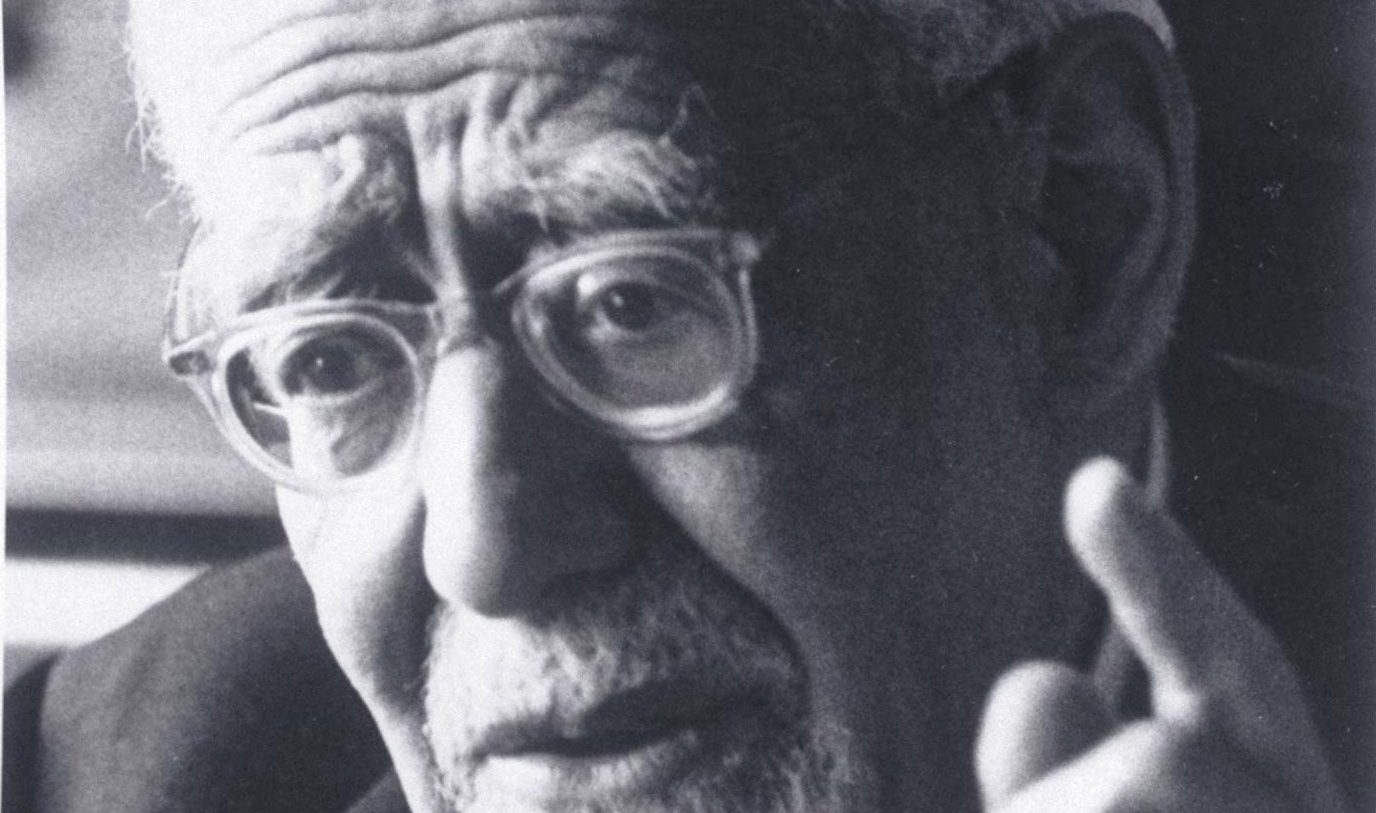

Leo Baeck (1873-1956) was one of the most profound and creative liberal Jewish theologians of the 20th century. Today, his name graces dozens of institutions of Jewish learning and scholarship across the world. But he is perhaps best known as the rabbi of Theresienstadt (a concentration camp also known as Terezin), a teacher who maintained his humanity and those of others in the face of Nazi brutality. His is a legacy of universal ethics and openness to the non-Jewish world, combined with an unwavering commitment to Judaism and his relationship with God.

Student, Teacher, Rabbi

Leo Baeck was born in the German town of Lissa (now Leszno in Poland). His father, Samuel Baeck, was a local rabbi and scholar. Leo was brought up in a traditional home, observing the dietary laws and engaging in daily Talmud study, but his father’s friendship with the local Calvinist minister taught him to appreciate the possibility of interfaith friendship and dialogue.

In contrast to his lifelong commitment to Judaism, Leo Baeck’s relationship with Jewish law — halacha — evolved over the course of his studies. After leaving his traditional home, he moved to Breslau and enrolled in the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Conservative rabbinical academy. But in 1894, Baeck left Breslau for Berlin’s Reform-oriented Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums — the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies — where he received his rabbinic diploma in 1897. Baeck’s rabbinic scholarship was complemented by his philosophical studies, first in Breslau and later under the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey at the University of Berlin.

Leo Baeck’s rabbinic career took him to communities in Silesia, Düsseldorf and, from 1912, Berlin. During World War I, he served as a military chaplain and saw service on both the eastern and western fronts. In addition to ministering to the troops, he tended to the spiritual needs of local Russian Jews.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Back in Berlin, Baeck’s relationship with his congregation’s leaders was never easy. His character was marked by an uncompromising commitment to scholarship and the pursuit of truth; his personality lacked dynamism, and he was far from gregarious.

Fritz Bamberger, a fellow German-Jewish scholar, remembered that, “when Leo Baeck preached, he did not talk down to an audience. Choosing each word carefully, building each sentence for measure and rhythm, speaking somewhat monotonously in a strangely vibrating high-pitched voice, now and then underlining a phrase with a movement of his sensitive hands, more often revealing the importance of a thought by an increased sharpness of his eyes, it appeared that he expected the response to his words not from his listeners but from somewhere beyond.”

Although one community leader labeled the rabbi’s sermons “Baeck’s private conversations with God,” the congregation accepted him as their leader and teacher.

Baeck’s Theology: The Essence of Judaism

Leo Baeck’s thought was part of a tradition of rationalist German Judaism that reached its apogee with Hermann Cohen, the 19th-century philosopher who characterized Judaism as the universal “Religion of Reason.” Cohen saw human reason as the foundation of universal ethics and the goal of religion as the realization of morality in the life of the individual.

Cohen — following Immanuel Kant — conceived of God as a “postulate of practical reason,” that is, an idea created by human beings to lend legitimacy to their autonomous, rational, ethical system.

But while philosophically sound, this approach was religiously problematic. Franz Rosenzweig related that Cohen once explained to an old Jew the idea of God which he had developed in his ethics. The old man listened attentively, but when Cohen had finished he asked him: “But where is the boreh olam, the creator of the world?”

This is a question that would have resonated with Baeck. Perhaps because of his rabbinical vocation, Baeck was concerned less with philosophical certainty and the idea of God than with his congregants’ real-life spiritual experience. Yet as a rationalist, he wanted to preserve morality as the foundation of Judaism. Was it possible to develop a theology that allowed for a living relationship with God and yet maintained the primacy of ethics? This is the question that drove Baeck’s theological quest.

Baeck’s best-known work, The Essence of Judaism, was written following the publication of Protestant theologian Adolf von Harnack’s Essence of Christianity, which compared Judaism unfavorably with Christianity. In response, Baeck described Christianity as a romantic, “feminine” tradition, based on feeling and grace. In contrast, he labeled Judaism as classical, “masculine,” and oriented towards ethical action. Christianity’s essentially non-ethical character could not be reformed by trying to graft on liberal principles, whereas the fundamentally moral basis of Judaism rendered it supremely compatible with modern values.

While Baeck agreed with Hermann Cohen that Judaism was, in its essence, ethical monotheism, Baeck argued that it stemmed not from an abstract philosophical idea but from the individual’s religious consciousness. So too, Jewish ethics had to be founded on religious certainty about a living God who dictates moral norms as part of his relationship with human beings. Thus Jewish theology reflected a tension between immanence — the individual’s personal relationship with God — and transcendence: God’s magisterial, law-giving aspect.

But why should we assume that ethics must be derived from religious consciousness and that the only correct response to God is an ethical one? The contemporary Reform theologian Eugene Borowitz notes that Baeck never adequately answered this question, claiming instead that his purpose, as a historian, was to describe how Judaism had always understood itself. But, if so, Baeck faced another insurmountable challenge: demonstrating that a dynamic, evolving tradition had an unchanging “essence” and that this essence was identical with his own modern, rationalist conception of Judaism.

At any rate, Baeck’s vision of ethical monotheism had two important practical implications. First, human autonomy, the responsibility to choose between good and evil, is at the center of Judaism. This is encapsulated in the traditional idea of teshuva–moral healing by means of a penitential return to God.

Second, in his later work This People Israel: The Meaning of Jewish Existence, Baeck reiterated his idea that ethics and not ceremonial law is the core of Judaism. Baeck distinguished between law — which he considered to be of human origin — and divine commandment, which inheres only in those ordinances which lead towards morality. Yet man-made ritual law plays an important role: to sustain the Jewish people, thereby creating a framework for the realization of the ethical. This is the universal meaning which Baeck ascribed to the apparently particularistic, even chauvinistic, concept of chosenness: only the Jews chose to make divinely grounded morality — ethical monotheism — the basis of their national, ethnic identity.

Baeck and the Nazis

Throughout his career, Baeck was sought out for positions of communal leadership. He was a member of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith, an organization committed to fighting German anti-Semitism, and a non-Zionist member of the Jewish Agency in 1897. But he wasn’t an anti-Zionist, and he had been one of only two rabbis to vote against the German Rabbinical Association’s condemnation of political Zionism.

After Hitler’s rise to power, Baeck refused all offers of escape, declaring that he would stay as long as there was a minyan of Jews in Germany. In 1933, he was elected founding president of the Representative Council of German Jews. At the organization’s first meeting, Baeck declared: “The thousand years history of German Jewry is at an end.” Nonetheless, he ceaselessly fought against the Nazi onslaught, working to provide social services to the devastated Jewish community and often negotiating directly with the Gestapo.

Theresienstadt

In 1943, Leo Baeck was deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. There he was put to hard physical labor on a garbage cart. Three of Baeck’s sisters had already died in the camp; one more perished after his arrival there.

Baeck was appointed honorary president of the camp’s Ältestenrat–the Jewish Council of Elders. He strove to preserve the humanity of those around him and ministered to Jewish and Christian inmates alike. Baeck took every opportunity to continue his work as a rabbi and scholar, discussing philosophy with fellow prisoners as his garbage cart progressed through the camp. In the evenings hundreds of people would crowd into a small barracks to hear Baeck lecturing from memory on the classics of Western humanism — Herodotus, Plato and Kant. When Baeck received word of the fate of millions of Jews in the extermination camps, he made the decision — criticized after the war — not to share this knowledge: “Living in the expectation of death by gassing would be all the harder. And this death was not certain for all…So I came to the grave decision to tell no one.”

Following the liberation of Theresienstadt in May 1945, Baeck prevented the camp’s inmates from killing the guards handed over to them by the Russians, and then stayed on to minister to the sick and the dying. Finally, he traveled on to London where he eventually served as chairman of the World Union for Progressive Judaism. He also lectured periodically at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.

Leo Baeck survived the war with his worldview intact. He interpreted the Holocaust as a failure of human morality which only served to underline his ethical commitment and his faith that “the way to our humanity does not lead away from our Judaism, it leads through our Judaism.”

Talmud

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

halacha

Pronounced: hah-lah-KHAH or huh-LUKH-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish law.

minyan

Pronounced: MIN-yun, meen-YAHN, Origin: Hebrew, quorum of 10 adult Jews (traditionally Jewish men) necessary for reciting many prayers.