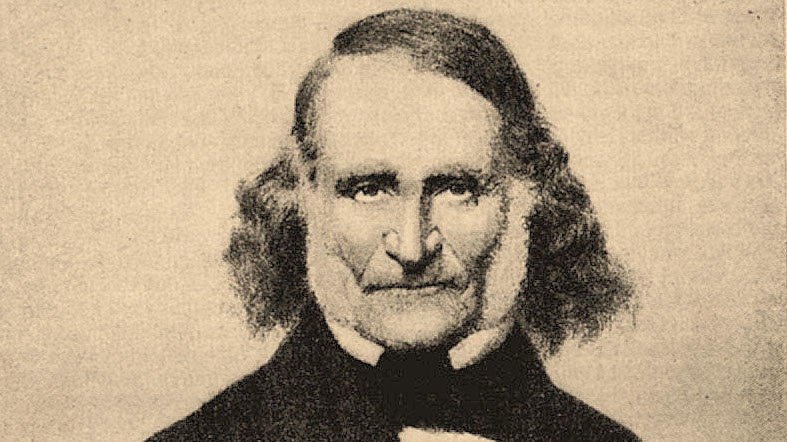

Leopold Zunz, a German Jew who lived from 1794-1886, was the founder of Wissenschaft, the “science of Judaism” that brought Jewish studies as an academic field into university settings. He was also a pioneer in studying the history of Jewish literature, religious poetry and synagogue rituals.

Zunz’s Hebrew name was Yom Tov Lippmann.

Zunz’ early years were marked by poverty and loss. His father, a student who worked as a teacher and tutor, died suddenly in 1802 and his mother died seven years later. Thanks to a scholarship from the Samson school at Wolfenbuttel, he enjoyed a rigorous Jewish and secular education and went on to be the first Jew admitted to the Wolfenbuttel Gymnasium, a prestigious high school.

At university in Berlin, Zunz studied mathematics, philosophy, history and philology, ultimately earning a Ph.D at the University of Halle. While in university, he copied the manuscript of of Shem-Ṭov Ibn Falaquera’s Sefer ha-Ma’alot and occupied himself with the study of Hebrew manuscripts from Palestine and Turkey.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In 1818, Zunz published a groundbreaking and influential book arguing for recognition of Judaism and its literature in university research and teaching. A year later, he founded, together with Eduard Gans and Moses Moser, the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden (Association for Jewish Science and Culture), a society intended “through culture and education to bring the Jews into harmonious relations with the age and the nations in which they live.” In 1822, Zunz edited Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft des Judenthums, (Journal of the Science of Judaism), publishing it under the association’s auspices. The journal introduced Wissenschaft, the new field of Jewish science, explaining that it consisted of studying the historical development and philosophical essence of Judaism through a critical understanding of Jewish literature. While the journal published only one issue, and the association itself disbanded, the “science of Judaism” which it had founded lived on, primarily due to Zunz’ work.

In 1832, Zunz published Gottesdienstliche Vorträge der Juden (Jewish Worship Practices), which the Jewish Encyclopedia (published in 1906) deemed “ the most important Jewish work published in the nineteenth century.” In it, Zunz traced the historic growth of synagogues and the gradual growth and evolution of Jewish homiletic literature (sermons), traced through the , the and the prayer book. Besides showing that the sermon was a thoroughly Jewish practice, the book demonstrated that Judaic studies could be an academic field and made the case that Judaism was a growing force, not a crystallized law. The book had a powerful influence in shaping the principles of Reform Judaism, especially as applied to the prayer books.

When a German royal edict in 1836 barred Jews from taking German names, the German Jewish community commissioned Zunz to write a scholarly paper on the history of Jewish names. The paper demonstrated that the names that had been classed as non-Jewish were actually an ancient inheritance of Judaism.

In 1840, Zunz became the first director of a new Jewish seminary, Lehrerseminar, where he was able to pursue academic research and writing, including a translation of the Book of Chronicles, a study on the geographical literature of the Jews and articles on German and Jewish issues of the day, particularly the rise of the Reform movement. Although his own work inspired it and though he neither strictly observed traditional Jewish laws nor believed they were divinely commanded, Zunz was no fan of the then-fledgling Reform movement. He regarded much of the professional life of its rabbis as a “waste of time” and objected to Reform critiques of the Talmud and Jewish ritual practice.

In 1845, Zunz published Zur Geschichte und Literatur (On History and Literature), whose opening chapter is a philosophical presentation of the essence of Jewish literature and its right to existence, its connection with the culture of the peoples among which the Jews have lived, and its bearing upon the civilizations amid which it developed.

In addition to his scholarly work, Zunz was active in German civic life. In 1848, he was appointed an elector in the 110th precinct both for the deputy to the Prussian legislature and for the representative in the German Diet (a legislative body). He was likewise busy in conferences and private interviews with influential citizens, endeavoring to carry into effect the emancipation of the Jews; in 1847 high functionaries of the court and state had sought his opinion on proposed legislation regulating the status of Prussian Jews. In 1862, he became president of his district electoral assembly.

Published in 1855, Zunz’ Synagogale Poesie des Mittelalters, (Synagogue Poetry of the Middle Ages) a study of the various kinds of poetry incorporated in Jewish liturgy. His Die Ritus des Synagogalen Gottesdienstes Geschichtlich Entwickelt (History of Synagogue Worship), published four years later, explored the historic development of different components of Jewish liturgy and in different parts of the world. Zunz’ work also included Monatstage des Kalenderjahres (Months of the Calendar Year), a memorial calendar published in 1872 that recorded the days on which great Jewish leaders and martyrs had died, and giving details concerning their labors and lives. Toward the end of his life, Zunz also became interested in the emerging field of biblical criticism.

Adapted from the Jewish Encyclopedia.

Kabbalah

Pronounced: kah-bah-LAH, sometimes kuh-BAHL-uh, Origin: Hebrew, Jewish mysticism.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.