The mishnah in Brachot 5:1 states that the original pietists, the chasidim harishonim, would wait an hour before they began prayer. The Talmud in Berakhot 30b expands on this to say that while the duration of each of the three daily prayers was an hour, each was preceded by an hour of waiting and followed by an hour, perhaps of processing.

When I taught Jewish meditation to high school students, I always started with this text. Students approach meditation, especially when adapted into a traditional Jewish prayer setting, with skepticism of its origins and authenticity. So this traditional rabbinic text offers a framework. What in fact happened during these hours of preparation and post-prayer? Is this something that we too might access without revising traditional Jewish prayer?

One might say that prayer is only as good as an individual’s centered mind and open heart. Eliminating distractions, increasing focus and mindfulness, setting intentions — all these are important to a meaningful prayer experience. Much has also been written about how prayer itself demands and develops the spiritual dispositions of gratitude, awe, and ecstasy. From Modeh Ani to Ahavah Rabbah, Jewish prayer continually prompts us to be grateful and to love greatly.

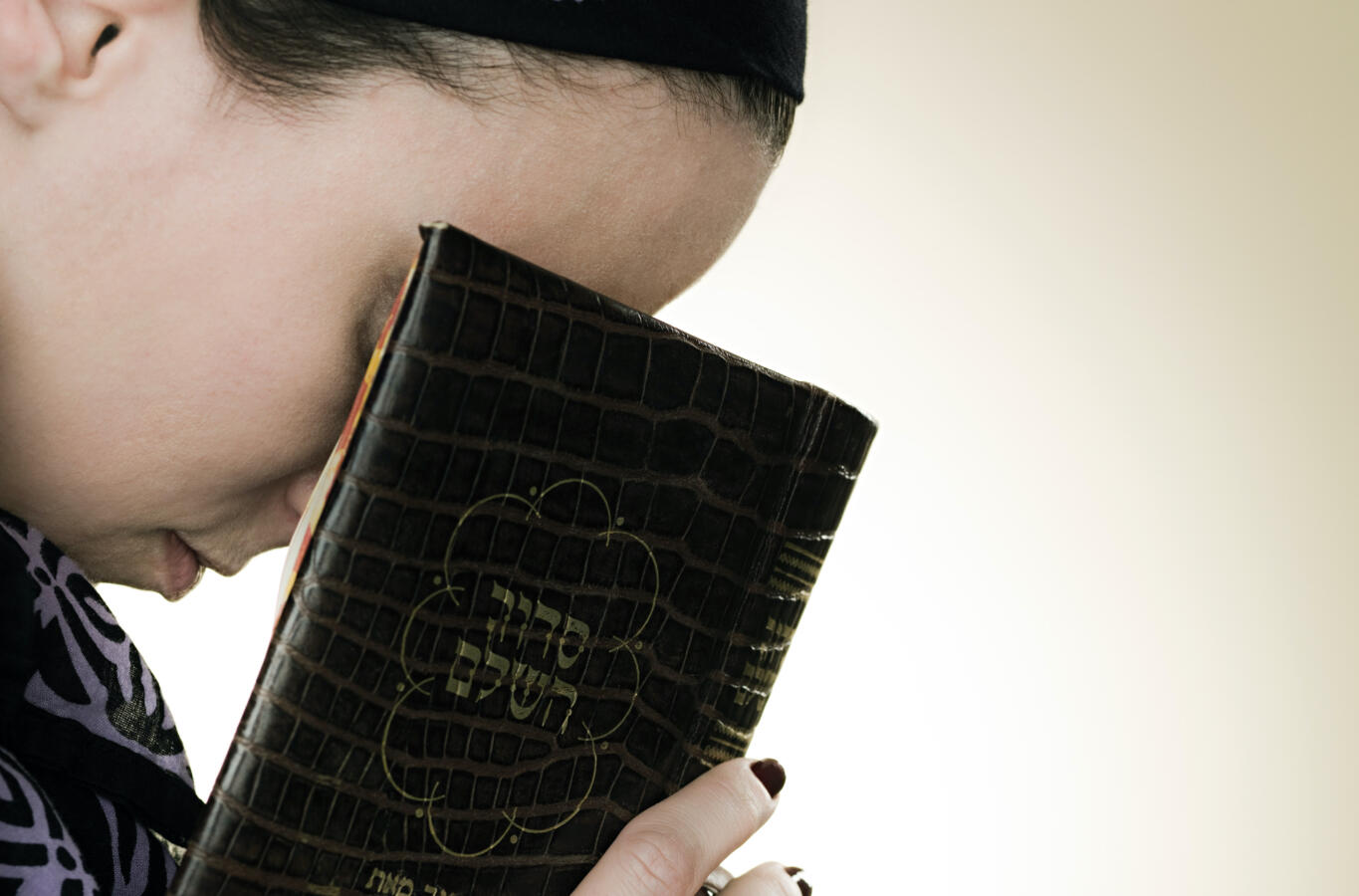

Yet this primary disposition of contemplation, of sitting in preparation and possibly in silence, seems foreign to Jewish prayer. Often we rush into prayer and rush out. For those who pray daily, prayer is often neatly scheduled into our day, like a class or a meeting. For many people, particularly those for whom prayer is understood as a religious obligation, it is often largely about saying the prescribed words, a ritualized exercise in recitation. What if instead we thought of prayer as first and foremost a listening space?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

In the introduction to his commentary on the prayer book, “Olat Reiyah,” Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook writes the following:

Prayer arrives in its ideal state

Within the thought

That the soul is always praying.

Is she not flying and embracing her beloved

Without interruption?

It is only that at the time of prayer practice

That the constant prayer of the soul

Is revealed and realized

The key term here is “constant prayer of the soul.” The soul, Rabbi Kook is saying, is always at prayer. When we sit in silence before prayer, we can watch and listen and integrate this naturally arising prayer into the scripted prayers of the liturgy. How do we cultivate this capacity to listen and notice as a core feature of Jewish prayer?

Before praying, try the following:

- Posture: Sit in an attentive posture on the edge of your seat, hands free and coming to rest on the knees, the senses attentive but stilled.

- Breathe: While sitting as still as possible, draw attention to the nose and belly, the way the breath is warmed in the noses and causes the stomach to expand and contract. Take a few deep breaths, counting to three with each inhale and exhale.

- Mind: Watch the incessant parade and loops of thoughts and refer back to steps 1 and 2 as you do. As thoughts and feelings arise, simply watch them. Becoming the watcher and not the thinker is a central teaching for not resisting, but simply noticing, acknowledging and even welcoming what arises.

- Listen: As thoughts become fewer and farther between, listen deeply to the activity of the soul. What emerges? What feelings, desires, or emotions begin to arise? Notice too the deep prayer of the soul. This heard prayer will fuel the articulated prayers soon to be spoken as you progress through the prayer book.

After sitting in this extended moment of anticipatory listening, we move into the liturgy. But take the silent preparation with you so that your prayers are saturated with both movement and stillness, with speaking and silence.

The standard morning prayer liturgy offers many opportunities for this. Notice that the first stage of the morning liturgy, the blessings of the morning (Birkot Hashachar), invite an awakening of the senses into the fullness of gratitude. As you recite the blessing Pokeach Ivrim, thanking God for opening the eyes of the blind, open your eyes and with gratitude let the liturgy guide your celebration of vision. The next stage of prayer, Pesukei d’Zimrah (Verses of Song) is where the soul bursts forth with an abundance of language. Yet at the heart of the prayer is the central verse of Ashrei — poteach et yadecha (“open your hand”) — which celebrates the receiving of God’s benevolence. It is a call to listen to the song of the natural world, which seems to celebrate its own creation at the start of this new day.

Then the liturgy shifts as we move into the Shema, the prayer whose very name means “listen.” This prayer is sandwiched by love: the blessing Ahavah Rabbah (“great love”), which invites us to listen to the love that saturates our choseness by God; and the paragraph Veahavta (“and you shall love”), where we listen to the love of a reciprocated commitment to observe God’s commandments. Having attended to the joy of creation, the soul now heeds the uniquely human joys of choosing and being chosen.

Finally, at the apex of prayer comes the silent Amidah, where we resolve this tension between speaking and silence. We at once ask for healing and declare our acknowledgment that God is the ultimate healer. We sway (or shuckle) and we stand still. We speak to God and we listen to God’s response. In these ways and others, this prayer speaks to the ways that prayer is both a deliberate conversation and a profound act of listening and acceptance.

In “Lonely Man of Faith,” Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik writes that prayer was initiated when the era of prophecy closed. But from Rabbi Kook we see that the listening to God continues, as an echo of prophecy, through the listening prayer of the soul.

In this vein, the early Hasidic master, Dov Ber of Mezeritch, wrote that the ultimate act of listening is to notice that the voice that speaks through the words of prayer is God’s voice merging with one’s own. In this way, the ultimate Jewish meditation becomes a radical act of listening to the constant prayer of your soul, which is itself part of God. He writes:

As a person begins to pray, reciting the words:

“O Lord, open my lips

and let my mouth declare Your praise,”

the Presence of God comes into him.

Then it is the Presence herself

who commands his voice;

it is she who speaks the words through him.

One who knows in faith

that all this happens within him

will be overcome with trembling

and with awe.