For many, Maimonides was the philosopher of Judaism par excellence. His philosophical masterwork, Guide of the Perplexed, was a sweeping attempt to reconcile traditional Jewish teachings with philosophical understandings. But it is his writings on Jewish law that have arguably proved more enduring. Maimonides himself understood that his statements on Jewish law would reach a larger audience, given his belief that his philosophical insights would inevitably be limited to a select few.

Mishneh Torah remains Maimonides’ most popular work, but it is just the capstone to a long and productive career writing on Jewish law. This work encapsulates Maimonides’ lifelong goals. Maimonides aimed to make Jewish law broadly accessible, doing away with the inconclusive debates of the Talmud and providing a simple halachic “bottom line” that any reader could understand. He also comprehensively reorganized Jewish law, re-categorizing the laws according to a system of his own devising. And he sought to integrate theology and philosophy into legal writings; he was perhaps the first medieval Jew to treat theological claims at length in a legal work and he was fond of highlighting the values and lessons of Jewish law.

Maimonides’s first major work on Jewish law, the Commentary on the Mishnah, was published in 1168. Ostensibly, this work provides a detailed explanation of the Mishnah, the foundational work of rabbinic law. But Maimonides does much more. He offers rulings in cases where the Mishnah offered opposing opinions, summarizes talmudic discussions, and frequently provides lengthy digressions on legal topics. It is these novel presentations that foreshadow the later reorganization of Jewish law in the Mishneh Torah. Maimonides also delves into theology, philosophy, psychology, ethics, and methods of interpretation.

Sign up here for “There Was None Like Maimonides,” My Jewish Learning’s email series about the legendary Jewish thinker.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

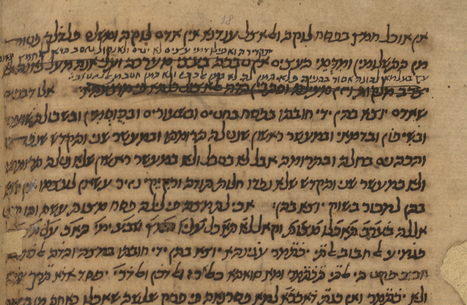

Remarkably—and uniquely for a medieval writer—the vast majority of Maimonides’s personal copy of this work survives to this very day, now held in libraries in Oxford and Jerusalem. The many crossouts and revisions evident in the manuscript bear witness to Maimonides’ commitment to perfect the Commentary on the Mishnah (and presumably, his other works as well). In some cases, Maimonides chose to reword the text to accord with a higher register of Arabic. In others, he changed his mind about how to rule in a particular matter or how to interpret a given passage. In still others, he developed a completely new attitude towards whole areas of Jewish law. This intimate access to Maimonides’ thought process is virtually unparalleled for any premodern writer, Jewish or otherwise.

Maimonides’s next legal work was a short book, The Book of the Commandments (Sefer Hamitzvot), which enumerated the 613 commandments of the Torah and explicitly set the stage for the broad overview of Jewish law that was to come in the Mishneh Torah. While earlier medieval Jews had dabbled in this project, Maimonides proudly writes of being the first to do so in a systematic manner. For Maimonides, identification of the 613 commandments served two goals. Most explicitly, it enabled him to substantiate his claim that the Mishneh Torah truly encompassed all of Jewish law. And it provided an opportunity to reflect on how Jewish law works.

Maimonides forcefully distinguishes between rabbinic and biblical law, describing the basis on which the rabbis asserted their authority to determine Jewish law and interpret the Bible. Maimonides also approaches the Hebrew Bible in a new way. Where the rabbis displayed no discomfort with fanciful readings of biblical verses, Maimonides consistently seeks more straightforward interpretations, even though he rarely deviates from rabbinic conclusions. And he tackles questions of legal classification that came to define the Mishneh Torah. Is taking the four species on Sukkot considered one or four commandments? On what authority did the rabbis institute the festival of Hanukkah? And are the punishments for violating the laws separate commandments or part and parcel of the law itself?

The Mishneh Torah draws on these features of his earlier writings, most markedly his attempt to move from the discursive nature of the Talmud to practical rulings and his sustained reorganization of the law. Maimonides very consciously chose to write the Mishneh Torah in Hebrew. He explains in the Book of the Commandments that the Mishneh Torah would adopt the more accessible Hebrew of the Mishnah, as opposed to the more limited Hebrew of the Bible or the abstruse Aramaic of the Talmud. He does not explain, however, why he did not write this work in Judeo-Arabic, the vernacular of the community in which he lived. He might have made this decision because he sought a readership beyond the Islamic world. Or he perhaps imagined that this work would become the guidebook once the Jewish people had re-established their political independence.

Maimonides viewed the Mishnah as a model in other ways too. He explains that topical divisions in the Mishnah are a model, but he in fact far exceeds that work’s arrangement scheme. The Mishnah is organized broadly by subject, but it also brings together laws in a more associative mode, sometimes because they were stated by the same rabbi and sometimes because rabbinic traditions shared linguistic features rather than a common subject matter. Maimonides invented entirely new divisions of Jewish law. For example the Mishnah does not really contain subcategories for tort or monetary law, so Maimonides created them. And unlike the Mishnah, Maimonides is incessantly attuned to the 613 commandments. Whenever relevant, he begins a subject with the relevant entry from that list.

Maimonides almost always omits the arguments of the ancient rabbis, whose debates about what the law should be make up the bulk of the Talmud. This approach created an uproar among later scholars, who bemoaned that in speaking in an authoritative voice, Maimonides did not “show his work.” Maimonides sometimes suggests that he simply wanted to offer clear guidance, but it is also evident that he felt that the intricacies of talmudic debate stood in the way of more important philosophical and theological matters. Many modern readers have suggested that Maimonides saw himself as the final arbiter of Jewish law and the Mishneh Torah as the ultimate guidebook for Jews, never to be superseded.

It’s likely that while Maimonides certainly sought unified practice among the Jewish people, he probably did not endow his decisions with ultimate authority or consider them true in any objective sense. It’s clear from his writings that he recognized that distilling the law from the Talmud is hardly straightforward and that qualified experts may reach different conclusions. Moreover, he often draws a sharp distinction between philosophical and legal truth, regarding the former as provable and the latter as more subjective.

Even if he did not produce the final word of Jewish law, no writer after Maimonides could ignore his contributions. He certainly did achieve his goal of making Jewish law accessible to both young and to old, to beginners and to his more advanced students. His drive to restructure the Jewish legal system opened new pathways for thinking about rabbinic traditions, pathways that continue to warrant sustained attention. And his attention to the superstructures of the law and to how each piece of the system fits into a seamless whole remains unsurpassed.