The superscription (1:1) of [Micah’s] book dates him to the days of the kings of Judah: Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah. According to this information (and we realize that the chronological data at our disposal are a bit uncertain), Micah appeared on the scene at the very latest in the year 734 (B.C.E.). He was active until at least 728, but perhaps much longer because his words are filled with the sense of imminent horror. Even if he did not experience the events themselves, he foresaw the inexorable incursions of Assyrian might in the destruction of Samaria in 722 and of Jerusalem in 701 (1:6-7; 3:12). He proclaims as the word of his God:

I am making Samaria a heap … ; I am pouring her rubble down into the valley; Her foundations I am laying bare.” (Micah 1:6)

Micah and Jerusalem

Later he must speak similarly of Jerusalem. Micah was, however, not living at his nation’s political center. His native town Moresheth lay some 20 miles southwest of the royal capital in the beautiful hill country of Judah, commanding a broad view across the coastal plain to the Mediterranean. But he was not a backcountry hermit either.

Lively contact with Jerusalem was assured by the fact that the Judaean kings maintained five fortress cities within a radius of less than six miles round about Moresheth. They were to protect the Judaean homeland from encroachments by the Philistine cities or attacks launched by the superpowers from the favorable staging area of the coastal plain.

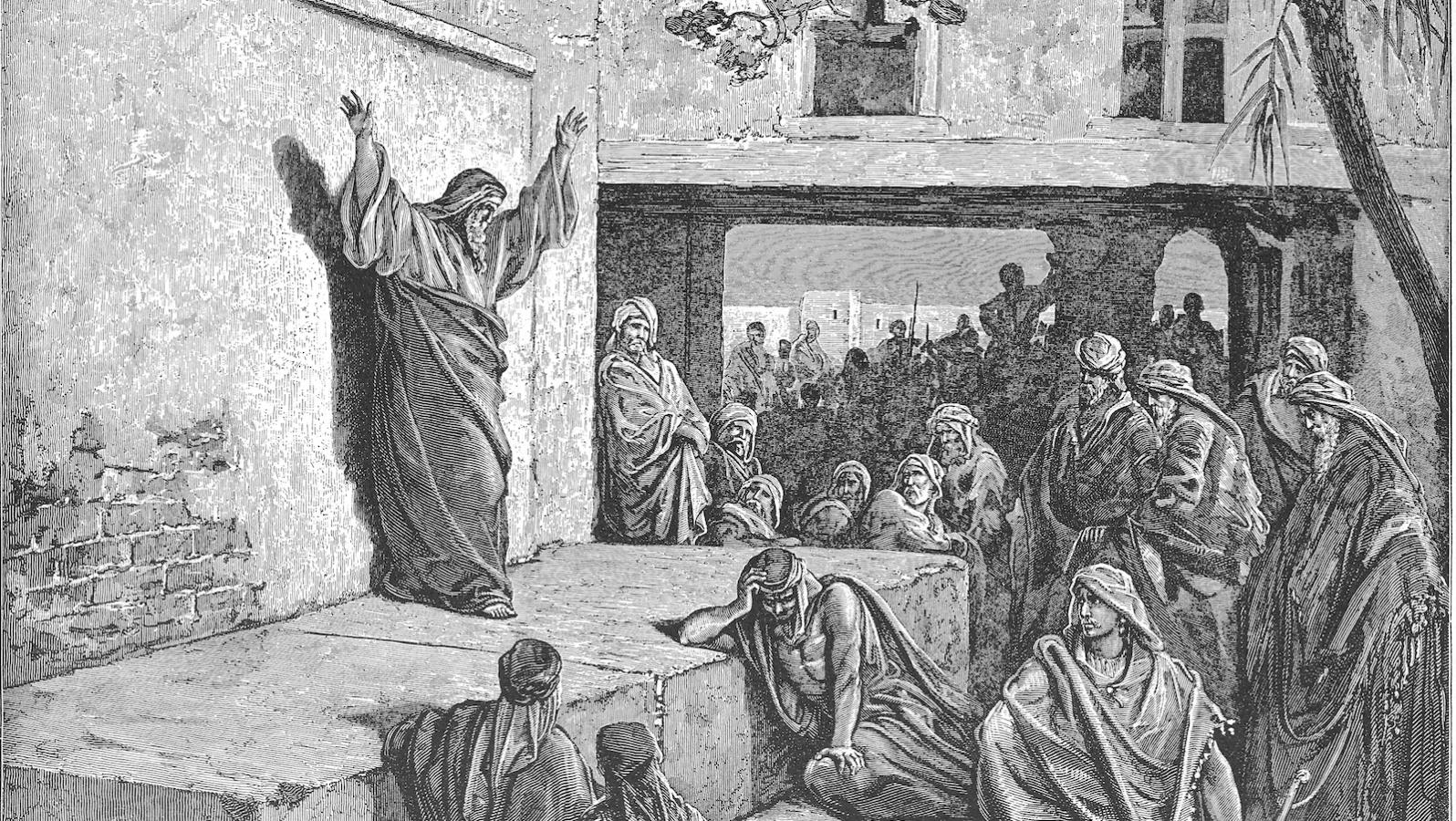

One thing, however, is indisputable: He appeared as a prophet in Jerusalem (Micah 3:9-10, 12). For, according to Micah 3:10, he addresses the leaders as those “who build Zion with blood and Jerusalem with wrong.” He threatens them, “Because of you . . . Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins” (Micah 3:12). We know no more about the external details of Micah’s life than these sparse references to the time and place of his activity. What holds true for all the prophets holds true for Micah: His life has disappeared behind the word which he was sent to proclaim.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

A Sense of Justice

From those sayings of his which have survived, we can draw a few conclusions about Micah’s self‑understanding and his relation to his fellow countrymen. The outline of his profile is the sharpest where he confronts his opponents: “But as for me, I am filled with authority, justice, and courage to declare to Jacob his transgression and to Israel his sin.” (Micah 3:8) What a testimony to fearless self‑assurance! Nothing in the other prophets comes close to it! One might, of course, suspect that this statement expresses the strained self‑glorification of a person obsessed with power (something which would not be very pious!).

But we are warned against such a misinterpretation by the commentary — like gloss which states that he possesses these gifts only along with “the Spirit of the Lord,” i.e., by virtue of the special divine authority which completely fills him. At the center of his gifts (between the gifts of “authority’ and “courage’) stands, according to his own statement, justice (that is, his sense of justice).

He does not have to say explicitly that here he is referring to the will of God. He underlines “justice” because he really is not dominated by the desires and whims of personal ambition, nor by pressures from members of his own party, nor by threats of his opponents. His full authority, his courage and sense of self‑assurance in taking a stand despite opposition, is derived from nothing else than the fact that he leaves no room within himself for anything except that sense of justice which completely fills him. This justice empowers him to reveal to Israel the unvarnished fact of its own injustice and lawlessness…

Micah’s Opponents

Micah opposes two groups. First, he opposes other prophets (3:5), and that means people who are his colleagues. They aim their word, Micah says, not in accordance with justice but with their own advantage…Whoever raises his voice as a prophet on behalf of justice will find, in a world of injustice, public opponents. The second group against which Micah speaks, therefore, are the responsible officials in Jerusalem, persons whom he addresses (3:1-9) as “leaders” and “rulers”…

Why does Micah attack these spiritual and secular authorities? Certainly not out of some abstract sort of fanaticism for justice. Why then? He addresses: (1) the prophets “because they lead my people astray” (3:5); (2) the political leaders in Jerusalem “because they eat the flesh of my people” (3:3); and (3) the officials at Moresheth because they “drive the women of my people out of the homes they love” (2:9). He addresses them all in general, “because they rise against my people like an enemy” (2:8). In all these passages it is clear that what motivates Micah is concern for his oppressed kinsmen.

Speaking Out Against Coveting, Perversions of Justice and Hypocritical Religiosity

Injustice shows itself, according to Micah, primarily in three activities: in coveting what belongs to others, in perverting justice, and in hypocritical religiosity. Selfish coveting is for Micah the source of all sorts of evil… Micah takes the word “covet’ from the ninth and 10th commandments (Exodus 20:17) and says: (2:2):

“They covet fields and seize them,

And houses, and take them;

they oppress a man and his family,

a man and his inheritance.”

One thinks immediately of officers and administrative officials from Jerusalem who are assigned to the fortress cities around Moresheth. They seek beautiful fields and houses in the pleasant countryside. Micah describes their psychology (2:1) as they keep themselves awake in bed at night, devising their plans. The next morning they carry out the plans “because it is in their power to do so.”

As a result of their imaginative planning their basic covetousness quickly matures into brutal acts of violence against property and people: property they “seize”; people they “oppress” (2:2). Both measures are strictly forbidden by God’s law, “Thou shalt not oppress thy neighbor or rob him” (Lev. 19:13)….

Micah must accuse Jerusalem’s leading officials in every field of one crime above all others–the hankering for money:

This city’s leaders give judgment for a bribe; its priests interpret the law for pay; its prophets give their revelations for money” (Micah 3:11)

Pronouncing Doom

Upon those who have been thus accused (of covetousness and greed) Micah pronounces doom most unambiguously. The very first word of Micah 2 strikes the basic note with its hoy (woe):

“Woe to those who lie awake and plan evil upon their beds, so that when morning comes they may perform it!”

Woe! Hoy! That is the cry of lamentation which was customarily heard throughout ancient Israel’s clans whenever death struck home. According to Micah’s adaptation of this woe, the selfish schemers are actually rotting corpses. Whoever pushes people aside in a selfish quest for things is pushing life aside and seeking death.

The prophet is not, however, proclaiming a general abstract proposition. His “Woe!” is an announcement, made ahead of time, of the evil‑planners’ doom. Their doom itself he describes in Micah 2:3-5: “Therefore thus says the Lord, ‘Behold, I am planning disaster!'” Man’s evil planning has already been encircled by God’s superior plan. Micah becomes more precise: “You will not remove your necks from disaster; you will no longer be able to walk uprightly (erect).” Micah even puts a dirge into their mouth: “We are utterly ruined. Our captors divide our fields.”

The Punishment Fits the Crime

Expropriation and expulsion threaten the expropriators and expellers. They fall into the pit they have dug for others. Elijah says to Ahab, according to I Kings 21:19, “In the place where dogs licked the blood of Naboth shall dogs lick your own blood.”

The punishment fits the crime. The false prophets are similarly threatened in Micah 3:5‑7. Those who twist God’s word to fit their own fancies will themselves receive no response from God (verse 7); those who aim at nothing but their hearers’ applause will find that God’s voice no longer speaks to them (verses 6‑7):

“The sun shall go down upon the prophets and the day shall be black over them; the seers shall be disgraced, and the diviners put to shame; they shall all cover their lips, for there is no answer from God.”

Those who do not want to be directed by God’s instructions will themselves soon no longer be able to bear any instruction from God. So neatly will the punishment fit the crime.

The worst threat is reserved for the responsible persons in Jerusalem (3:10) who “build Zion with blood and Jerusalem with wrong.” Blood‑guilt and injustice are not foundations capable of hearing the weight that must be borne; they are, in fact, fatal traps:

“Therefore because of you Zion shall be plowed as a field; Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins, and the Temple Mount will be given over to the beasts of the forest” (Micah 3:12).

Reprinted with permission from Micah the Prophet (Fortress Press).