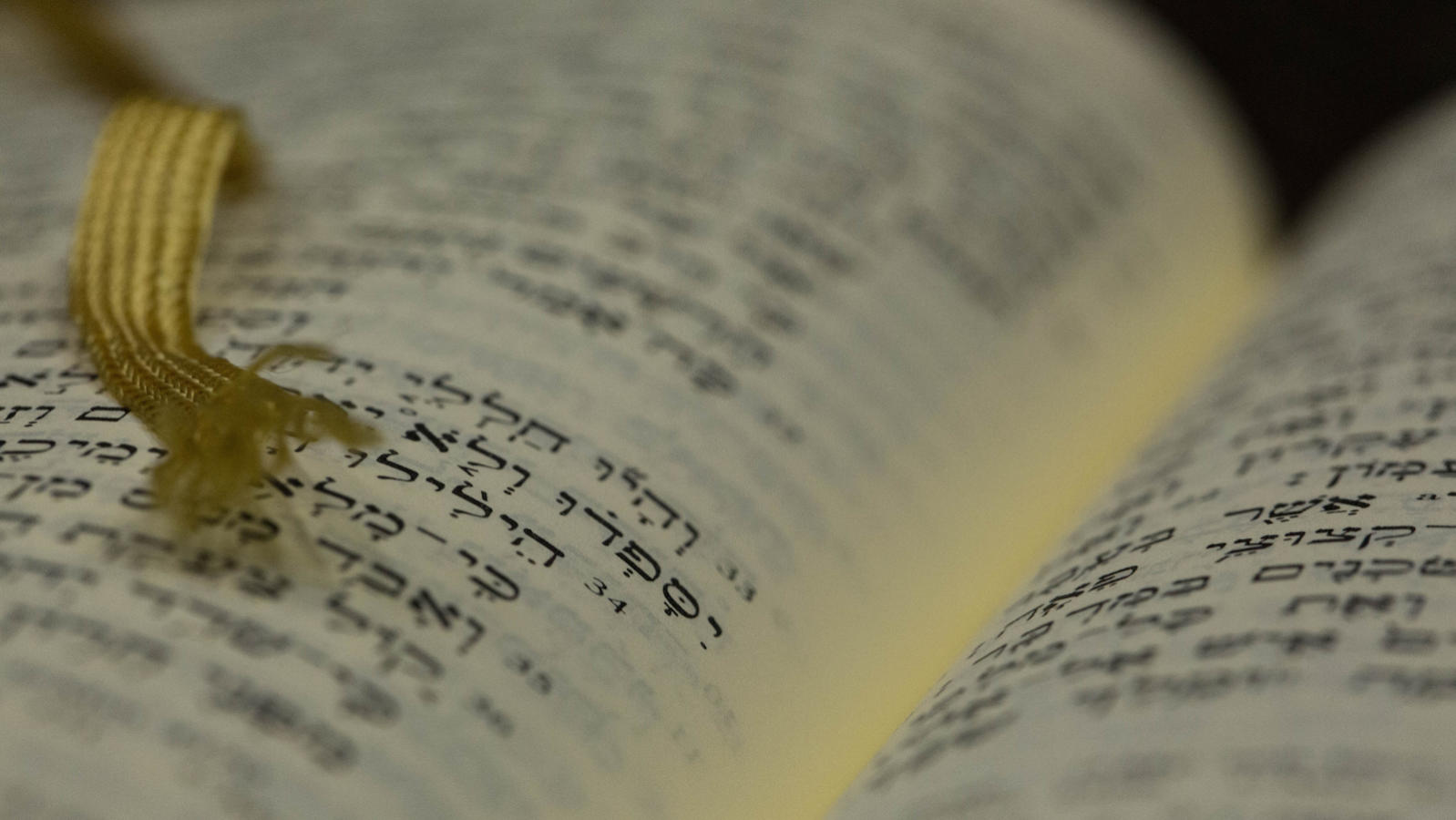

The history of Torah is one of interpretation. Every seemingly superfluous letter, unclear transition and difficult phrase invites discussion, explanation and elaboration. This interpretive tradition has produced volumes and volumes of midrash –stories, homilies, parables and legal exegesis based on the biblical text. These texts offer a glimpse of the ways that people of various times and places have grappled to understand the biblical text and to make it meaningful for their own lives.

Midrash Rabbah, the Largest Collection of Aggadah

The body of literature known as midrash is generally divided into aggadic (narrative) and halakhic (legal) midrash. Collections that contain mostly stories, parables, and homilies are classified as midrash aggadah, while collections focused primarily on the derivation of law are called midrash halakhah.

The largest volumes of midrash aggadah are often referred to collectively as Midrash Rabbah. This name is actually a misnomer, as this group of texts comprises 10 unrelated collections, compiled over the course of eight or more centuries. Each volume comments on one of the five books of the Torah (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) or of the five Megillot (Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes and Esther).

Some scholars trace the name Rabbah to the first line of B’reishit Rabbah (Genesis Rabbah), which begins, “Rabbi Oshaya Rabbah opened.”

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Just as books of the Bible often draw their names from the first significant word of the text, this book of midrash also seems to have acquired the name of the first rabbi quoted in it. Others argue that the title Rabbah, which means “great” or “large,” is intended to distinguish this book from a smaller volume that must once have existed. Whatever its origin, the term “Rabbah” later came to be applied to the largest collections of aggadic midrash on each of the five books of the Torah and the five Megillot. In turn, shorter collections of aggadic midrashism on a few of these books acquired the designation, Zuta, which means “small” in Aramaic.

B’reishit Rabbah and Vayikra Rabbah

The oldest extant aggadic midrashimare B’reishit (Genesis) Rabbah and Vayikra (Leviticus) Rabbah. Both were probably compiled around the fifth century CE, but each includes material dating back at least to the third or fourth century. These midrashim (the plural of midrash) are written in a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic, and are peppered with Greek words and expressions.

B’reishit Rabbah consists of a mixture of line-by-line commentary, parables, popular sayings, and legal principles. Many of the best known midrashim, including the story of Abraham breaking his father’s idols, appear in this collection.

One notable characteristic of B’reishit Rabbah, as well as of a number of other aggadic midrashim, is the prevalence of the petihta (known to scholars as a “proem,” meaning “preface”), a roundabout method of explaining a given verse. The petihta begins with a citation from elsewhere in the Bible–usually from Psalms or Proverbs–and then explicates this text so that it eventually leads back to the verse in B’reishit.

Vayikra Rabbah is classified as a “homiletic midrash,” meaning that the text consists of a series of expository sermons, rather than of a line-by-line commentary. Each of these homilies introduces one parashah (weekly Torah reading) according to the ancient cycle of readings, in which the Torah was read consecutively over the course of three years.

Each homily in Vayikra Rabbah focuses on one theme that emerges from the parashah being introduced. For example, the first verse of Leviticus, “God called to Moses,” inspires a long meditation on Moses’ qualities and on his special relationship with God. The prohibition against drinking wine before undertaking divine service (Leviticus 10:9) prompts a discussion on the dangers of alcohol. Other verses spark discussions about poverty, reward and punishment, and appropriate interpersonal behavior. With their emphasis on topics of general interest, these homilies help ordinary people to find relevance in the book of Leviticus.

Devarim Rabbah

Devarim (Deuteronomy) Rabbah is made up of 27 homilies, corresponding to the divisions of the book according to the ancient triennial reading cycle. Scholars have dated this text as early as 450 CE and as late as 800 CE. Each homily in Devarim Rabbah addresses a halakhic (legal) question and each generally concludes with a statement about redemption.

For example, the text begins with a reference to the first words of the Book of Deuteronomy, “These are the words that Moses spoke,” and then launches into a discussion about the permissibility of writing a Torah scroll in a language other than Hebrew. The midrash goes on to consider a range of other subjects, including the importance of rebuke and the value of Torah, and eventually concludes with a promise that, in the messianic era, God will bless the Jewish people directly rather than via religious functionaries.

The last section of Devarim Rabbah consists of a lengthy and sometimes astounding discussion on the death of Moses. In describing the moment of Moses’ death, the midrash imagines a powerful battle of wills, in which Moses prays for life and God bolts the doors of heaven lest Moses’ prayer enter and overturn the divine will. The angel of death tries and fails to kill Moses, the angels Gabriel and Mikhael refuse to participate in taking Moses’ life, and Moses’ soul refuses to leave his body. Finally, in accordance with the biblical text, God descends to give Moses the kiss of death and then to bury him.

Sh’mot Rabbah and Bamidbar Rabbah

The Rabbah midrashim on the books of Exodus and Numbers were probably compiled in the early medieval period, though each also includes older material and, in some cases, the vestiges of a previously-edited work of midrash.

Most scholars understand Sh’mot (Exodus) Rabbah to be a combination of two separate works, each probably written sometime between the ninth and eleventh century CE. The first half of the midrash offers a line-by-line commentary on the first ten chapters of the book of Exodus, and the second half consists of a series of homilies on chapters twelve through forty. Similarly, Bamidbar (Numbers) Rabbah comprises an exegetical commentary on the first seven chapters of the book of Numbers and a homiletic commentary on the rest of the book. The first part of Bamidbar Rabbah is notable for its inclusion of esoteric material and for its apparent familiarity with Sefer Yetzirah, an early work of Jewish mysticism. The second half of Bamidbar Rabbah is essentially identical to Midrash Tanhuma on the book of Numbers. The development of the first half of this text may have taken place as late as the twelfth century CE, while the second half may have existed as early as the fourth century CE.

The Five Megillot (Scrolls)

Between the fifth and eighth centuries, a Rabbah developed for each of the five Megillot–the biblical books read on the holidays of Passover (Shir Hashirim/Song of Songs), Shavuot (Ruth), Tisha B’av (Eicha/Lamentations), Sukkot (Kohelet/Ecclesiastes), and Purim (Esther).

Eicha (Lamentations)

In keeping with the themes of the book of Eicha, which describes the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE, Eicha Rabbah (fifth century) offers a series of homilies that elaborate on the themes of displacement, suffering, and hopelessness. Most striking are the midrashim that depict God as actively destroying Jerusalem in order to punish the Jewish people, and then mourning for the loss of the city and its people. In some of these midrashim figures including the angels, the Torah, and various biblical characters plead with God to save the Jewish people; in others, God retreats into a private mourning, refusing any consolation.

Ruth

Like Eicha Rabbah, Ruth Rabbah, also composed around the fifth century, amplifies the themes of the book on which it is based. The book of Ruth includes numerous examples of tzedakah (monetary gifts to the poor) and g’milut hasadim (acts of loving kindness), and the midrash spends significant time expounding on these themes. This midrash also spends some time locating the story of Ruth within the larger biblical context by reading references to Ruth and her family into verses from the book of Chronicles.

Shir Hashirim (Song of Songs)

Shir Hashirim Rabbah (sixth century)is most notable for its allegorical interpretation of the biblical text. Read literally, Shir Hashirim consists of some fairly racy poetry describing the relationship between two lovers. In the hands of the midrash writers, the book becomes a G-rated description of the love between God and the Jewish people. Consider, for example, the midrashic interpretation of the verse, “All night between my breasts my love is a bundle of myrrh (1:13)”:

“My love is a bundle of myrrh.” What does “a bundle of myrrh” mean? Rabbi Azariah, in the name of Rabbi Yehuda, explained that this verse refers to Abraham. Just as myrrh is first among the spices, so too is Abraham first among the righteous…”all night between my breasts.” For he was considered to be halfway between an angel and the divine presence (Shir Hashirim Rabbah 1:14).

Thus, what seems at first like a sexy bedroom scene is transformed into a lesson about the righteousness of Abraham who, according to this midrash, achieves near-divine status.

Kohelet (Ecclesiastes)

Some have suggested that Kohelet Rabbah, written between the sixth and eighth centuries CE, may originally have served as a school textbook. Through a verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Kohelet, this midrash addresses an unusually wide range of topics, ranging from business practices to the cycles of nature to the character and limits of wisdom. This collection includes a significant amount of material taken from other midrashim and from the Palestinian and Babylonian Talmuds.

Esther

The volume known as Esther Rabbah can be divided into two sections. The first half, compiled around 500 CE, is an exegetical commentary on the first two chapters of the book of Esther. Like other midrashim of its time, this collection begins with a number of petihtaot introducing the first line of the biblical book. Given the notable absence of the name of God from the book of Esther, the midrash makes a special effort to find within the biblical text hidden references to divine intervention.

The second part of Esther Rabbah was composed significantly later, perhaps around the eleventh century. This section comments on the remaining chapters of the biblical book. Most surprisingly, this half of Esther Rabbah includes Hebrew translations of several passages of the Septuagint, the first Greek edition of the Bible, published in the third century BCE.

The Rabbahs include midrashim of a variety of styles, themes, and time periods. Though different from each other in many ways, all of these works help to bring the biblical text to life by adding stories and interpretations, and by drawing out of the biblical text lessons for everyday life. Most importantly, these midrashim remind us that the Bible has infinite meanings, and that each individual and each generation reinvigorates it by developing new interpretations.

Purim

Pronounced: PUR-im, the Feast of Lots, Origin: Hebrew, a joyous holiday that recounts the saving of the Jews from a threatened massacre during the Persian period.

Shavuot

Pronounced: shah-voo-OTE (oo as in boot), also shah-VOO-us, Origin: Hebrew, the holiday celebrating the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, falls in the Hebrew month Sivan, which usually coincides with May or June.

Sukkot

Pronounced: sue-KOTE, or SOOH-kuss (oo as in book), Origin: Hebrew, a harvest festival in which Jews eat inside temporary huts, falls in the Jewish month of Tishrei, which usually coincides with September or October.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.