After World War II, both international and domestic courts conducted trials of accused war criminals. Beginning in the winter of 1942, the governments of the Allied powers announced their determination to punish Axis war criminals. On Dec. 17, 1942, the leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union issued the first joint declaration officially noting the mass murder of European Jews and resolving to prosecute those responsible for crimes against civilian populations.

Signed by the foreign secretaries of the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, the October 1943 Moscow Declaration stated that at the time of an armistice persons deemed responsible for war crimes would be sent back to those countries in which the crimes had been committed and judged according to the laws of the nation concerned. “Major” war criminals, whose crimes could be assigned no particular geographic location, would be punished by joint decisions of the Allied governments. The trials of leading German officials before the International Military Tribunal (IMT), the best known of the postwar war crimes trials, took place in Nuremberg, Germany, before judges representing the Allied powers.

Trials of High-Ranking Nazis

Between October 18, 1945, and October 1, 1946, the IMT tried 22 “major” war criminals on charges of crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, and conspiracy to commit such crimes. The IMT defined crimes against humanity as “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation…or persecutions on political, racial, or religious grounds.” Twelve of those convicted were sentenced to death, among them Reich Marshall, Hermann Göring, Hans Frank, Alfred Rosenberg and Julius Streicher. The IMT sentenced three defendants to life imprisonment and four to prison terms ranging from 10 to 20 years. It acquitted three of the defendants.

Under the aegis of the IMT, US military tribunals conducted 12 further trials of high-ranking German officials at Nuremberg. These trials are often referred to collectively as the Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings. Between December 1946 and April 1949, US prosecutors tried 177 persons and won convictions of 97 defendants. Leading physicians, Einsatzgruppen (mass-killing squads) members, members of the German justice administration and German Foreign Office, members of the German High Command and leading German industrialists were among the groups who stood trial.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The overwhelming majority of post-1945 war crimes trials involved lower-level officials and functionaries. In the immediate postwar years, the four Allied powers occupying Germany (and Austria) — the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union — held trials in their zones of occupation and tried a variety of perpetrators for wartime offenses. Many of the earliest zonal trials, especially in the U.S. zone, involved the murder of Allied military personnel who had been captured by German or Axis troops. In time, however, Allied occupiers expanded their juridical mandate to try concentration camp guards and commandants and others who had committed crimes against Jews and others who suffered persecution in areas the Allies now occupied. Much of our early knowledge of the German concentration camp system came from the evidence and eyewitness testimonies at these trials.

Allied occupation officials were interested in a denazification of Germany and saw the reconstruction of the German court system as an important step in this direction. Allied Control Council Law No. 10 of December 1945 authorized German courts of law to pass sentence on crimes committed during the war years by German citizens against other German nationals or against stateless persons. For this reason, occupation officials left Euthanasia crimes — where both victims and perpetrators had been predominantly German nationals — to newly reconstructed German tribunals. These proceedings represented the first German national trials in the early postwar period. Both the German Federal Republic (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) continued to hold trials against Nazi-era defendants in the decades following their establishment as independent states. To date, the Federal Republic (in its old manifestation as West Germany and in its current status as a united Germany) has held a total of 925 proceedings trying defendants of National Socialist era crimes. Many detractors have criticized German proceedings, particularly those held in the 1960s and 1970s, for doling out acquittals or light sentences to aging defendants or defendants who claimed superior orders.

Nazi-Occupied Nations and Nazi Collaborators

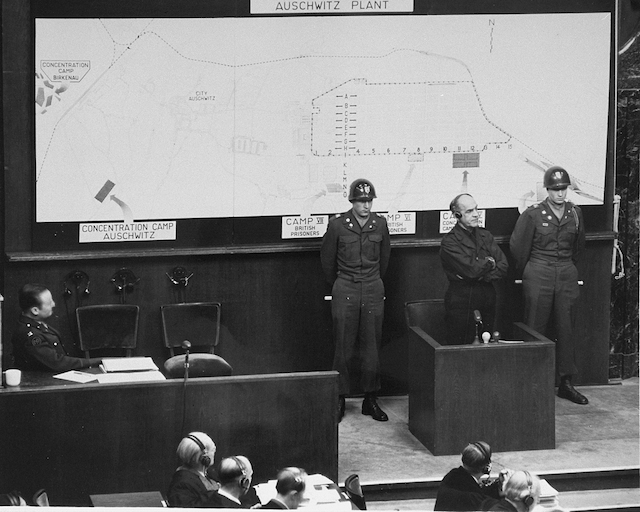

Many nations that Germany occupied during World War II or who collaborated with the Germans in the persecution of civilian populations, especially Jews, have also held national trials in the years following World War II. Poland, the former Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Hungary, Romania, and France, among others, have tried thousands of defendants—both Germans and indigenous collaborators, in the decades since 1945. The Soviet Union held its first trial, the Krasnodar Trial, against local collaborators in 1943, long before World War II had ended. Perhaps Poland’s most famous postwar national trial was held in 1947 in Krakow. The proceedings tried a number of functionaries of the Auschwitz concentration camp and sentenced Auschwitz camp commandant Rudolf Höss and others to death. One of the most famous national trials of German perpetrators was held in Jerusalem: the trial of Adolf Eichmann, chief architect in the deportation of European Jews, before an Israeli court in 1961 captured worldwide attention and is thought to have interested a new postwar generation in the crimes of the Holocaust.

Unfortunately, many perpetrators of Nazi-era criminality have never been tried or punished. In many cases, German perpetrators of National Socialist crimes simply returned to their normal lives and professions in German society. The hunt for German and Axis war criminals still goes on today.

Reprinted with permission from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Holocaust Encyclopedia.