All Jews living in the Christian culture of Western society have felt the discomfort that comes with standing on the sidelines while our neighbors celebrate their winter holidays. Most of us are diligent about respectfully disassociating ourselves from the obvious religious implications of Christmas.

The “civil” New Year, on the other hand, appears to be another matter altogether. This is a day that does not have any denominational message, a mere symbolic commemoration of the start of a new year in the calendar that we all use in our day-to-day lives.

When we look back to the ic sources, however, we find that our ancient rabbis make explicit reference to New Year’s, whereas the celebration of Christmas was, as far as I know, quite unknown to them.

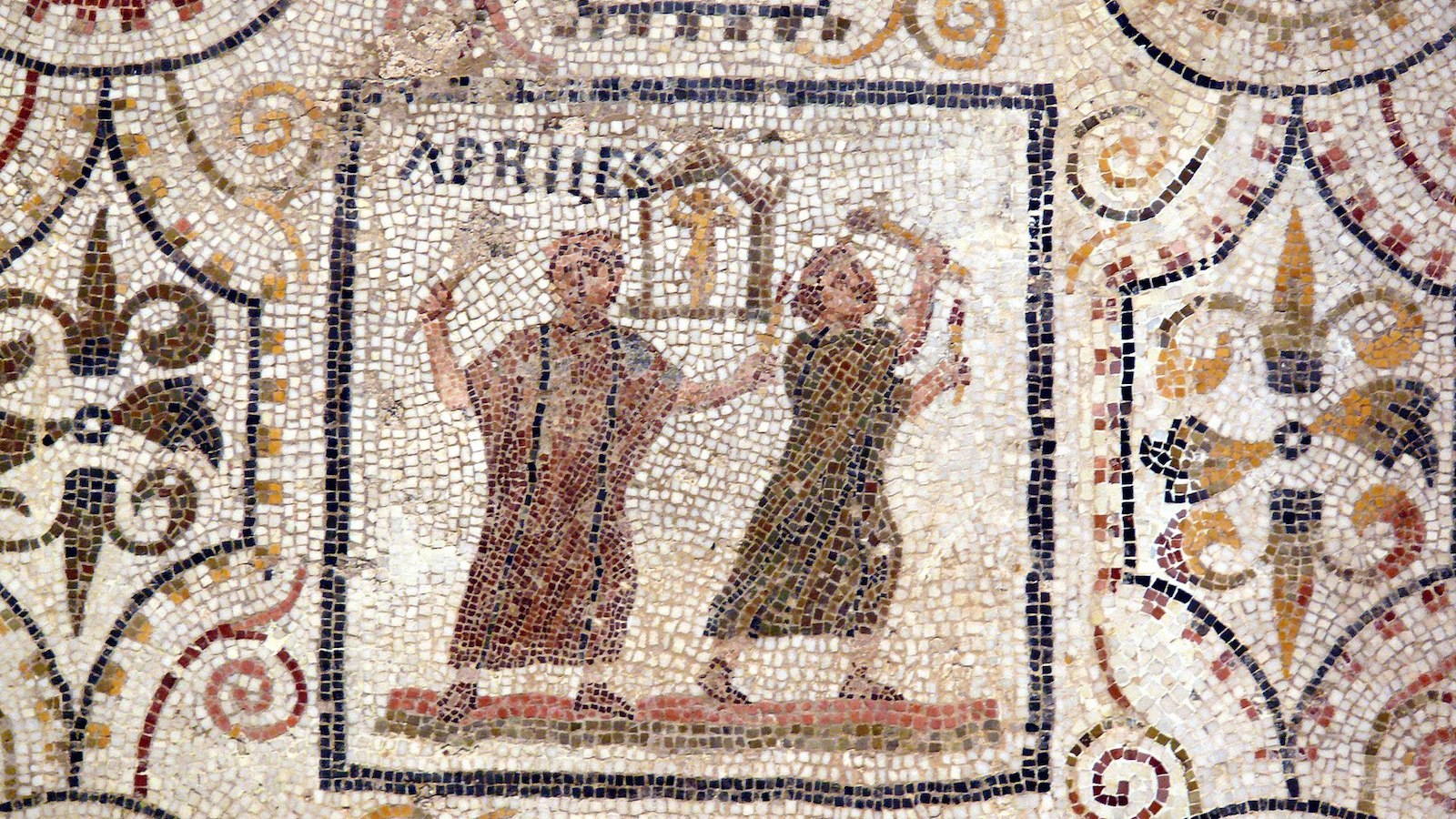

The passages in question speak of the Roman festival of the “Kalends,” that is, the Kalendae Januariae (etymologically related to our English word “calendar”), which was celebrated as the New Year in Roman times. The day is mentioned in the Mishnah (Avodah Zarah 1:3) as part of a list of various Roman festivities on which Jews are required to avoid doing business with the pagans so as not to add to the worshipper’s pleasure or appear to be showing honor to their idols.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Though they were aware that these festivals were being observed throughout the Roman world, the talmudic sages were not always clear about their purposes and origins. They offered some interesting suggestions about how the Kalends came to be and why it was celebrated in the way it was.

Adam’s Celebration

One assumption that the rabbis frequently held was that pagan religion was somehow a corruption of authentic biblical traditions which had become misunderstood with the passage of time. Accordingly the Talmud would look for precedents for the respective holidays in the actions of the ancestors of these nations, including figures such as Esau (he was, according to rabbinic tradition, the progenitor of the Romans) or Adam, the father of all mankind.

Following this premise, for example, the Talmud records that the Egyptians’ cult of Serapis had originated in their veneration of Joseph. Another source relates how the Egyptians had come to worship the ibis birds because Moses had used them in his military campaigns against the Ethiopians. Many similar instances of this phenomenon could easily be adduced.

A comparable approach was used by the prominent third-century Babylonian teacher Rav to explain the origin of the Roman New Year. According to Rav’s account it was Adam, the first man, who had instituted the Kalends.

Since in the very first year of his life he had no way of knowing the cyclical seasonal changes that occur in the lengths of the days, Adam became very disturbed when the first winter began to approach and he saw that the days were getting shorter and the nights longer. He began to fear that the day was being consumed by a cosmic serpent, and that the pattern would persist indefinitely until daylight disappeared altogether.

This dread continued to trouble Adam until the arrival of the winter solstice, when the pattern began to reverse itself and the days began to lengthen. At this point, relates Rav, Adam–in an allusion to what would become known as the Kalends–exclaimed Kalon dio, a Greek phrase which has been construed by assorted modern scholars as meaning, “Praise be to God,” “Beautiful day,” or “May the sun set well.”

From that day onward, the Talmud concludes, the day of the solstice has been observed by Adam’s descendants, though the original reason may have been garbled in the transmission.

A Mythological Motif

Another noted talmudic rabbi, Yochanan, proposed a different explanation of the origin of the Kalends. According to this version the story has nothing to do with biblical history, but goes back to a heroic exploit in Roman history.

Once, during a war between Rome and Egypt, the two sides, recognizing the futility of continued combat, decided to award the victory to whichever general would agree to sacrifice his life by falling on his sword. The Roman general, an old man named Januarius, was persuaded to pay the ultimate price when he was assured that his twelve sons would be honored with noble titles as dukes, hyparchs, and generals. After he had performed the heroic deed, they renamed the day in his honor “the Kalendes of Januarius.”

It would appear the Rabbi Yohanan has interpreted the New Year Festival as a purely national holiday without any objectionable religious connotations. A closer look at the story however reveals some clearly mythological motifs.

For example, the 12 sons bear a suspicious resemblance to the twelve months of the year that are being renewed at this point in time. The general Januarius reminds us of the two-faced Roman divinity Janus who is actually being honored on this day and who gives his name to the first month.

According to some scholars Janus was originally worshipped by the Etruscans as a god of Light and Day–a connection which fits in very nicely with Rav’s legend of Adam and the shortening days. As a two-faced deity, Janus was believed to look simultaneously at the past and the future, and hence he was selected as the appropriate god for the new year.

Though a similar account of a King Janus is recorded in a later Christian source, that story is certainly not referring to an actual historical event. Some scholars have explained that underlying Rabbi Yochanan’s account is an old myth about how the ancient god Janus, the father of Time, died to make room for his twelve sons, the twelve months.

Presupposed by all these talmudic explanations is the firm conviction that January 1st is not merely a Roman civil holiday, but a pagan religious celebration. According to the Talmud, by participating in its festivities, Jews would be showing honor to idols and to their most hated enemy, the “Kingdom of Wickedness,” Rome.