Commentary on Parashat Toldot, Genesis 25:19-28:9

- Rebecca has twins, Esau and Jacob. (Genesis 25:19-26)

- Esau gives Jacob his birthright in exchange for some stew. (Genesis 25:27-34)

- King Abimelech is led to think that Rebecca is Isaac’s sister and later finds out that she is really his wife. (Genesis 26:1-16)

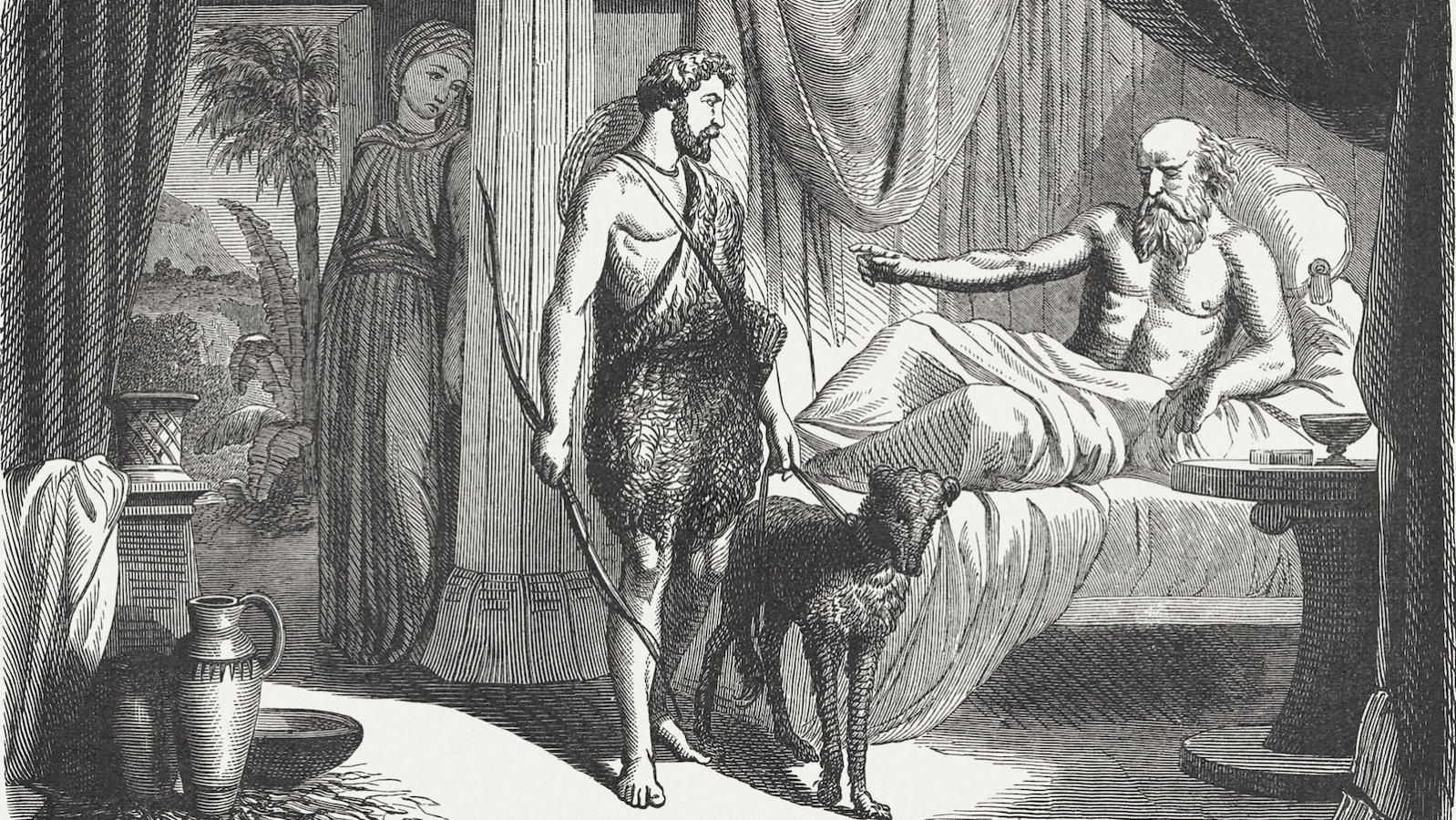

- Isaac plans to bless Esau, his firstborn. Rebecca and Jacob deceive Isaac so that Jacob receives the blessing. (27:1-29)

- Esau threatens to kill Jacob, who then flees to Haran. (27:30-45)

Focal Point

This is the story of Isaac, son of Abraham. Abraham begot Isaac. Isaac was 40 years old when he took to wife Rebecca, daughter of Bethuel the Aramean of Paddan-aram, sister of Laban the Aramean. Isaac pleaded with Adonai on behalf of his wife, because she was barren; and Adonai responded to his plea, and his wife, Rebecca, conceived. But the children struggled in her womb, and she said, “If so, why do I exist?” She went to inquire of Adonai (Genesis 25:19-22).

Your Guide

Why does the text say that Isaac is the son of Abraham and then repeat that Abraham begot Isaac?

This week’s Torah portion gets its name, Toldot, from the second word in the first verse. This word comes from the root y–l–d, meaning “bring forth” or “beget.” It is translated as “story” in the Plaut Commentary and as “progeny” in a translation by A. Silbermann (Pentateuch with Rashi’s Commentary). Does the translation of this word shape our understanding of the Torah portion as a whole?

Why is Rebecca’s genealogy longer than Isaac’s?

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

The Hebrew phrase l’nochach ishto in verse 21 is translated as “on behalf of his wife” in the Plaut Commentary, while the Silbermann translation is “facing his wife.” Both translations are accurate. What do we learn from each one?

Do you think it is significant that three of the matriarchs — Sarah, Rebecca, and Rachel — are barren for many years?

Why are the children struggling in Rebecca’s womb?

By the Way…

“Abraham begot Isaac:” This is the way in which Abraham and Isaac moved toward holiness: They both knew that it was not through their individual merit but through the merit of their fathers and their children.(Yehiel Malchsander in Itturei Torah I on Genesis 25:19).

“Isaac pleaded with Adonai:” (Genesis 25:21) R. Azariah said in the name of R. Hanina b. Papa: Why were the matriarchs so long childless? In order that they should not put on airs toward their husbands on account of their beauty. R. Hiyya b. Abba said: Why were the matriarchs so long childless? In order that the greater part of their lives should be spent without servitude. R. Levi in the name of R. Shila said: Why were the matriarchs so long barren? Because the Holy One, blessed be God, longed to hear their prayers (Song of Songs Rabbah, chapter II,14:8).

“On behalf of his wife:” (Genesis 25:21) This teaches that Isaac prostrated himself in one spot and she in another (opposite him), and he prayed to God: “Sovereign of the universe! May all the children that Thou will grant me be from this righteous woman.” She, too, prayed likewise (Genesis Rabbah 38.5).

“Facing his wife:” He stood in one corner and prayed, while she stood in the other corner and prayed. (Rashi on Genesis 25:21)

“Facing his wife:” We need to understand why they prayed from opposite sides. R. Yehoshua b. Levi explained (Bava Batra 25): Later on, the men of the Great Assembly decided the direction one should be facing while praying. But because Isaac and Rebekah did not yet know the proper place to pray, they came up with a plan: Isaac would stand in one corner and Rebekah in another corner so that one way or another, one of them would be facing the right direction (Mayim Chayim in Itturei Torah I on Genesis 25:21).

“The children struggled within her” (Genesis 25:22). R. Johanan said: Each ran to slay the other [deriving the word “struggled,” vayit’rotz’tzu, from the root r–u–tz, meaning “run”]. They sought to run within her. When she stood near synagogues or schools, Jacob struggled to come out. When she passed idolatrous temples, Esau eagerly struggled to come out” (Genesis Rabbah 53.6).

“Only connect.” (E. M. Forster, Howard’s End, chapter 22)

Your Guide

Both Rashi and the Mayim Chaim (commentator Chaim ben Bezalel) prefer the translation “facing his wife,” yet they offer different interpretations of the scene. Rashi’s interpretation evokes the boxing ring–Rebecca in one corner, Isaac in the other, both waiting for the bell. This competitive vision is tempered by that of the Mayim Chayim, who transforms the antagonists into a pious couple. From your understanding of these two characters, is there truth in either or both of these interpretations?

The translation of l’nochach ishto as “on behalf of his wife” presents Rebecca as mute while Isaac prays for her. Why does Genesis Rabbah add, “She, too, prayed likewise”? Compare this midrash with that of Song of Songs Rabbah. What is Rebecca’s role in these explanations? Does God want to hear women’s prayers as well as men’s?

Does Yehiel Malchsander’s understanding of the reason for this portion’s consuming interest in genealogy express a model of family dynamics that is consonant with the rest of our reading this week?

The reason for the struggle between the children in Rebecca’s womb offered by Genesis Rabbah 53.6 escalates and deepens the twins’ uterine activity. What do you think is the commentator’s purpose for giving this explanation?

D’var Torah

If only relationships were as simple as the recitation of lineage seems to be: “Abraham begot Isaac” and so on. Yet the opening verses of this portion show us that each familial relationship and, by extension, all human relationships are far more complex. We plunge immediately into the harsh, competitive world of Isaac and his family. We see this clearly in Genesis 25:22: Our first piece of information about Jacob and Esau is that even in the womb, they fight. From here the portion chronicles their conflict and the deterioration of their family’s structure. It’s easy to see why Genesis Rabbah develops this prenatal struggle into a murderous ideological conflict.

It is possible that there is a premonition of the twins’ rivalry even before verse 22. The two translations of the phrase in the preceding verse l’nochach ishto, “on behalf of his wife” and “facing his wife,” offer two models of existence open to Isaac and Rebecca and their sons — unity and openness or conflict and deceit. That both these options exist during a moment of prayer may hint that their choice of union or separation (whether we refer to Rebecca and Isaac or to Jacob and Esau) is embedded in their own constant spiritual struggle with their relationship with God.

“Only connect,” E. M. Forster urges, yet we see that both the crowded conditions in Rebecca’s womb and the empty space between Rebekah and Isaac reflect the difficulty to fulfill Forster’s command. The opening lines of the Torah portion prepare us for the bleak sadness of its end. Both sons leave. The old couple, Rebecca and Isaac, are left alone, the continuation of their line uncertain. Will they be able to close the gulf between them? If they cannot connect with each other, can they connect with God? Can we?

Provided by the Union for Reform Judaism, the central body of Reform Judaism in North America.

Torah

Pronunced: TORE-uh, Origin: Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses.