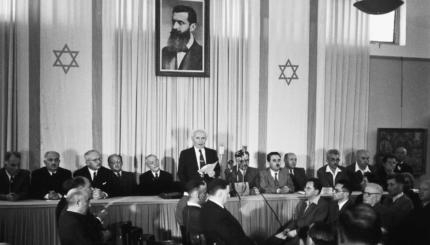

The following article examines the secret negotiations that occurred in Oslo between the PLO and the Israelis in 1992 and 1993. These negotiations led to the formulation of an agreement regarding the possibility of peace. The agreement, deemed “The Declaration of Principles,” was signed in Washington in September 1993. The article is reprinted with permission from A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Times published by Alfred A. Knopf.

Although unofficial discourse between Israelis and PLO members had been taking place since the 1970s, those contacts intensified only after 1992, when the Rabin government decided to eliminate all further legal constraints against them. No meetings occurred on Israeli soil. Both sides preferred other, neutral venues. One of those was Stockholm. Another was Oslo. There the Institute for Applied Social Science, a respected think tank devoted to the resolution of international disputes, functioned under the unofficial imprimatur of the Norwegian foreign ministry.

In the spring of 1992, the institute’s director, Terje Rod Larson, who had developed extensive PLO contacts in the course of field studies in the Gaza Strip, sought out Dr. Yossi Beilin, a protégé and close advisor of Shimon Peres. Larsen informed Beilin that key PLO members had confided to him their fatigue with the Intifada, and their willingness to explore the accommodation Arafat had mooted [Israel’s right to exist in peace and security] as far back as the winter of 1988. Beilin was interested.

After Labor’s electoral victory of June 1992, Peres appointed Beilin his deputy in the foreign ministry. Larsen’s wife, Mona Juul, by then was administrative assistant to Norwegian Foreign Minister Johan Jorgen Holst and accordingly in a position to offer Beilin the services of the Norwegian government. In turn, sensing that the bilateral discussions in Washington had reached a dead end, Beilin brought the proposal to Peres.

The foreign minister did not veto it. Yet he cautioned Beilin to avoid “official” Israeli involvement. Operating under this guideline, Beilin selected two “unofficial” representatives, Professor Yair Hirschfeld and Dr. Ron Pundak of Haifa University. Hereupon Arafat selected as his principal negotiator “Abu Ala’a” (Ahmed Suleiman Khoury), the PLO “minister of finance” who had long functioned virtually as the chairman’s alter ego.

The foreign minister did not veto it. Yet he cautioned Beilin to avoid “official” Israeli involvement. Operating under this guideline, Beilin selected two “unofficial” representatives, Professor Yair Hirschfeld and Dr. Ron Pundak of Haifa University. Hereupon Arafat selected as his principal negotiator “Abu Ala’a” (Ahmed Suleiman Khoury), the PLO “minister of finance” who had long functioned virtually as the chairman’s alter ego.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In January 1993, under cover of Larsen’s institute, Hirschfeld, Pundak, Abu Ala’a and two Palestinian aides were secretly accommodated in a luxurious private mansion outside Oslo. Discussions began. From the outset, both sets of negotiators agreed that the most realistic objective was an interim accord, essentially a declaration of principles, on Palestinian “empowerment.” Both Israelis and Palestinians would require time to develop trust and mutual interests.

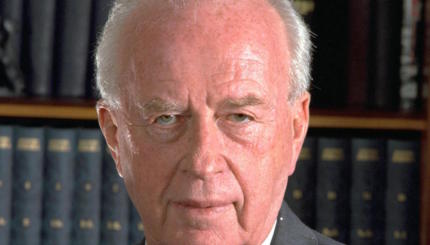

To that limited end, negotiations then continued over the ensuing weeks, with Larsen always in the background to provide for every physical need, and on occasion to function as a mediator between the two sides. Periodically there were serious disagreements, and both sets of negotiators returned to Jerusalem and Tunis for further consultations. Then, in late February 1993, Yitzchak Rabin finally was brought into the picture. Cautiously, the prime minister allowed the initiative to continue, although without shifting his focus on the “official” bilateral negotiations in Washington.

By then, too, both sides were concentrating on the Gaza Strip as the likeliest site for an early Israeli withdrawal and Palestinian “empowerment.” A suppurating pesthole, Gaza in any case evoked little historic resonance even among Israeli hard-liners. Indeed, under Peres’s instructions from Jerusalem, Hirschfeld and Pundak intimated a willingness to add Jericho to Gaza as a locale for early Israeli withdrawal.

As the foreign minister saw it, Jericho’s proximity to the River Jordan improved the chances of an eventual confederation between the Palestinians and Hashemite Jordan, the political scenario that Peres had always favored. To Arafat and his advisors, by the same token, the dusty little town of 14,000 represented a kind of preliminary lien on the West Bank. They were interested.

Thus, by late spring 1993, anticipating a breakthrough, both the Israelis and the PLO upgraded their representatives in Oslo to “official” status. Although maintaining a cover of secrecy, Beilin himself made periodic visits to share in the discussions. At the same time, Peres discreetly alerted Egypt’s President Mubarak to the backdoor negotiations and won his cooperation in encouraging Arafat to move forthrightly toward an accommodation. Others who quietly fostered the negotiation process were the Americans: for Secretary of State Warren Christopher similarly had been apprised of the Oslo channel. Christopher’s Middle East negotiator, Daniel Kurtzer, shuttled between Tunis and Jerusalem, seeking to narrow the gap between the PLO and the Israelis.

The combined efforts eventually bore fruit. At long last, Abu Ala’a and his colleagues were authorized to diverge for the Palestinian stance in the Washington negotiations: the explosive issue of Jerusalem would be postponed. Manifestly the distance was narrowing between security, of decisive concern to the Israelis, and self-rule, which mattered most to the Palestinians.

By August 1993, the basic outline of a “Declaration of Principles” was emerging. Yet, even then, Arafat in Tunis was fearful of taking the final step. Accordingly, Rabin and Peres sent word through Beilin that Israel would be prepared to recognize the PLO as official spokesman for the Palestinian people.

The concession was exceptionally painful for the two Israeli leaders. Neither had to be reminded of the many hundreds of Israelis and other Jews who had died by guerilla violence over the years. Yet they sensed now that public acknowledgement of Arafat’s legitimacy as the one and official Palestinians spokesman was an inducement the PLO chairman could not easily reject. The gesture was a shrewd one, and it worked.

So did Peres’s final gamble, on August 17, of alerting the PLO leadership that the time for procrastination was over, that his own and Rabin’s patience had expired, that the Declaration of Principles must be completed that very night. The Israeli Foreign Minister was in Stockholm, ostensibly to attend an international Socialist congress. Through the Norwegian foreign minister—also present—a series of back and forth telephone calls to Arafat in Tunis clarified the few remaining points at issue.

When the PLO chairman still hesitated, Peres threatened to break off all further contacts and negotiate exclusively with Syria. Hereupon Arafat wilted. Without further demurrer, he accepted the final draft of the outline of the Declaration of Principles. The next day, Peres flew secretly to Oslo and was present at the Norwegian government guest house as his appointed delegate Uri Sair, director general of Israel’s foreign ministry, signed the document for his government while Abu Ala’a and his young aide Hassan Asfour signed for the PLO.

Even then, Rabin would not submit the document to his cabinet. If he had paid the bitter price of recognizing the PLO’s official status, he expected repayment in kind. On September 9, he got it. It was a formal letter from Arafat. In black and white it affirmed that the PLO acknowledged Israel’s right to exist in peace and security; that the PLO renounced the use of terrorism and other acts of violence; and that “those articles of the Palestinian Covenant which deny Israel’s right to exist… are now inoperative and no longer valid.” In response, the prime minister’s letter of September 10 (a single, icily formal paragraph) confirmed that the “Government of Israel has decided to recognize the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people and to commence negotiations with the PLO within the Middle East peace process.”