Commentary on Parashat Achrei Mot, Leviticus 16:1-18:30

This week’s Torah reading is Achrei Mot (“After the Death” ), which concerns the death of Aaron’s sons and its aftermath, which is narrated twice in the Book of Leviticus. The stories are told differently in each instance. Why?

We read the first version several weeks ago in Parashat Shmini, where we learn that two of Aaron’s four sons, Nadav and Avihu, both priests, “offered alien fire before the LORD.” (Leviticus 10:1) What is alien fire? The particulars of their offenses are notably vague. But the consequences are not vague at all: God sent fire to punish them and they died.

Moses responds to this punishment by essentially telling Aaron that his sons deserved it. Moses sees fit to defend God, claiming the swift deaths enhanced God’s glory.

How does Aaron respond to Moses’ certainty about the guilt of his sons and the will of God? He was silent.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Rightfully so — and as I read it, not just because of his grief. I imagine Aaron was offended and even shocked by his brother’s words. Can we know why any death happens? Can we say someone deserved to die?

It’s not uncommon for those mourning the untimely deaths of loved ones to want to understand why God could have let it happen. There is only one answer that can be responsibly offered: We don’t know.

Aaron’s silence is arresting, but hardly surprising. It confirms what we know: Deaths cannot and should not be explained away. There is only more pain for a mourner who is counseled to move on by rationalizing the bad thing that happened, especially when it is interpreted as a punishment from God.

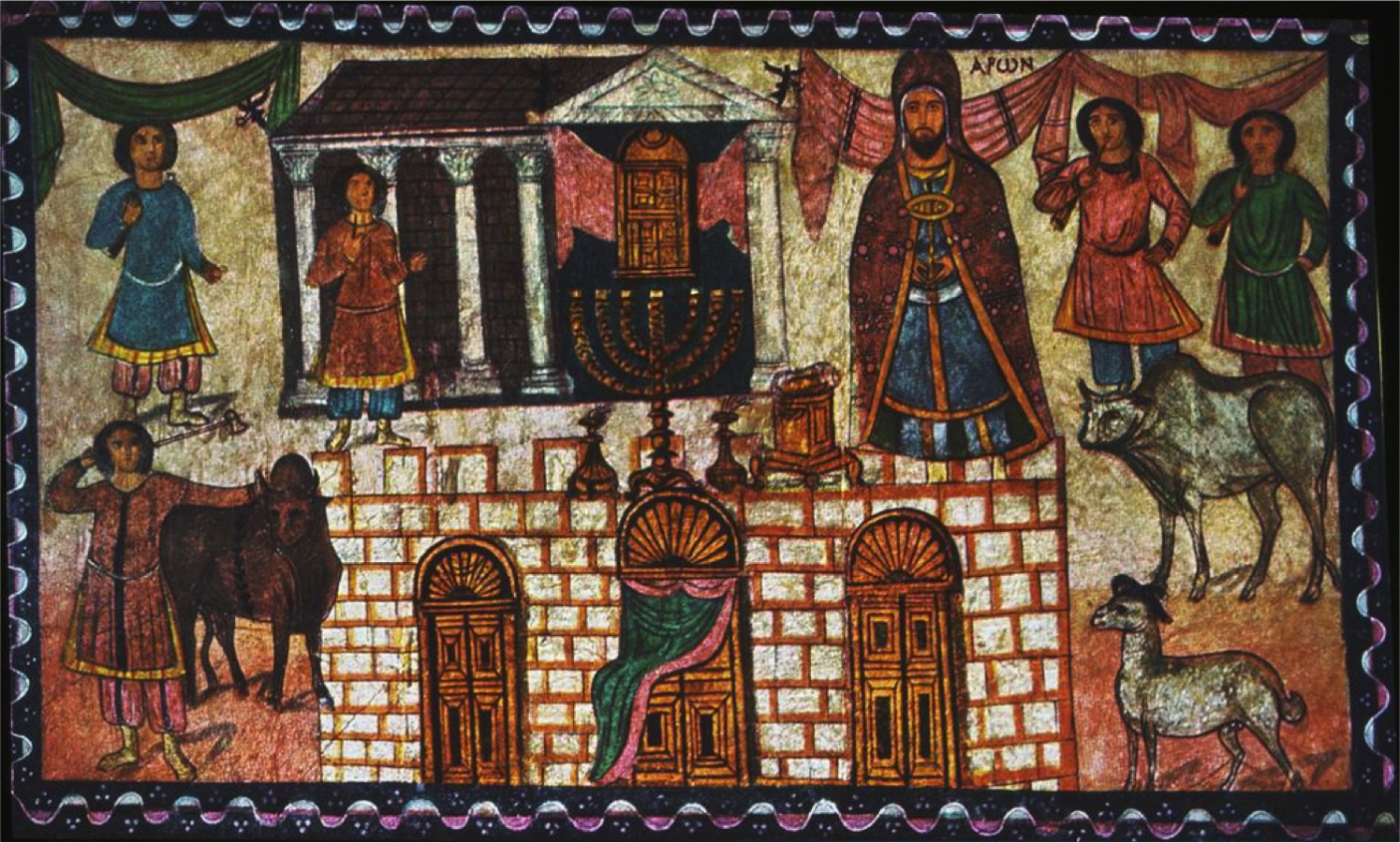

In Achrei Mot, the story of the death of Aaron’s sons is told again. Perhaps in the retelling, we will learn more about Aaron’s emotional and spiritual response. But no. Aaron is denied space to mourn — to feel anger, outrage, guilt. Instead, the text moves immediately to describing the complex sacrificial rituals of penance that Aaron, as high priest, must perform for the community on Yom Kippur. As is often the case in such situations, Aaron’s is seemingly enjoined to carry on for the sake of others.

But the midrash on this Torah portion does reveal the response of Elisheva, the mother of Nadav and Avihu and Aaron’s wife. There is a tradition that identifies Elisheva as one of the midwives who spared the Jewish boys born to the Hebrew slaves in Egypt.

Unlike her husband, Elisheva is not silent in her grief. She is not reduced to silence by those who would explain her sons’ deaths away. She is not made to lose herself in busyness. Starkly put, any joy Elisheva knew was “turned to mourning.” (Leviticus Rabbah: 20:2)

In another midrash, Elisheva is described as having begun her day proudly witnessing the important holy work of her sons. But “when her sons entered to sacrifice, they came out burnt, and her celebration was transformed to mourning. Immediately she became like columns of smoke.” (Shir Hashirim Rabbah 3:6)

In the days and weeks after a death, even ones that come after a long life, it is common to tell the story of what happened over and again, as if it might reframe how the experience is processed. Achrei Mot, in this repeated telling, opens the door to the midrash to imagine a bereft mother shrouded in pain and grief. One can only hope that she models this honest response for her husband and that she invites him to feel his feelings as well.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Reading Torah Through Grief newsletter on April 28, 2023. To sign up to receive this newsletter each week in your inbox, click here.

Looking for a way to say Mourner’s Kaddish in a minyan? My Jewish Learning’s daily online minyan gives mourners and others an opportunity to say Kaddish in community and learn from leading rabbis.