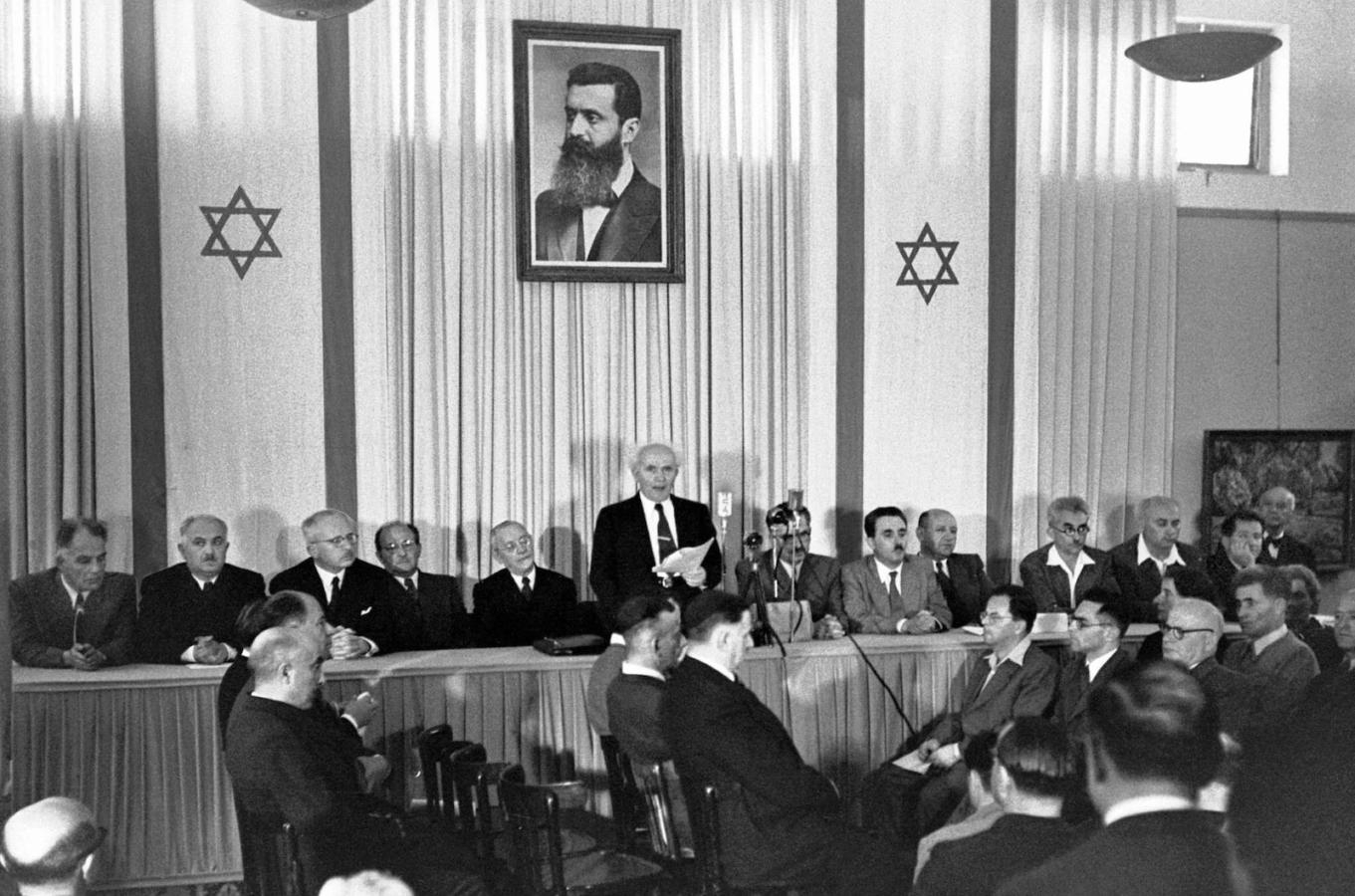

Almost immediately after Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948, some Jewish communities established the corresponding Hebrew date, the 5th of Iyyar, not merely as a civic holiday, but also as a Jewish religious holiday.

But the question remained: How should such a day be religiously commemorated? What rituals and liturgy would be appropriate?

Within a year of Israeli independence, the Bible scholar Rabbi Ezra Tziyon Melamed suggested that the closest analogues to Yom Ha’atzmaut are the holidays of Hanukkah and Purim. The tradition since talmudic times has been to add the Al Hanisim (“For the Miracles”) prayer to the daily Amidah and Grace After Meals on these holidays, which recall times when the Jewish people were miraculously saved from danger.

Melamed composed a version of Al Hanisim for Israel’s Independence Day that would later be published by the Israel’s religious kibbutz movement. In this version, the story of Israeli independence is told with special focus on the struggle against the British — “an empire of wickedness” that “closed the gates of our land before our brethren, fleeing from the sword of an evil enemy, and returned them in ships to islands and banished them to coasts.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Melamed’s version thanks God who “in your strength, cast his throne to the ground and freed the land from his hand” and references the Arab states that attacked the newly born State of Israel. As in the Hanukkah version of Al Hanisim, Melamed’s prayer thanks God for granting “the strong to the hand of the weak, the many in the hand of the few, and the wicked in the hand of the righteous.”

Most Orthodox Jewish communities have chosen not to recite Al Hanisim for Yom Ha’atzmaut, probably out of a reticence to tamper with the traditional text. Since 1961, however, Conservative Jewish prayer books in the United States have included their own version of Al Hanisim for Yom Ha’atzmaut. The movement published that year includes a version of Al Hanisim that tells the story quite differently.

Unlike Melamed’s version, the 1961 version spends the entire first paragraph focused on the Holocaust: “In the days of world-wide war and destruction, six million of our people were brutally slain because they bore Your name. Age-old communities were devastated, their sanctuaries desecrated, their houses of learning razed, and their sacred treasures burned. It was then that scattered remnants of the helpless and the homeless sought refuge with their brothers in the Land of our Fathers.”

In this version, the British are not mentioned by name and limitations on Jewish immigration are referred to only in the passive voice: “When the gates to our ancestral home were closed …” Like the Melamed version, the second paragraph focuses on the Arab effort to eliminate Israel and thanks God for delivering “the many into the hands of the few, the guilty into the hands of the innocent.”

A revised version of the Al Hanisim for Yom Ha’atzmaut is found in Siddur Sim Shalom, first published in 1985, and subsequent liturgical publications of Conservative Judaism in the United States. This version frames Israeli independence not simply as a response to the Holocaust, but more directly honors the Zionist movement and its state-building efforts that long predated World War II. The Holocaust is referenced only allusively: “the gates to the land of our ancestors were closed before those who were fleeing the sword.” The primary focus of this version, like those that came before it, is on Israel’s struggle with its Arab neighbors.

Slightly different versions of Al Hanisim for Yom Ha’atzmaut also appear in the prayerbooks of the Israeli Reform and Conservative (Masorti) movements. There have also been various independent efforts to create new versions of Al Hanisim for the holiday, each choosing a slightly different set of historical elements to emphasize.

The contrasts in these various versions of Al Hanisim remind us that the way Jews tell the story of the creation of the State of Israel is constantly evolving, with one major point of disagreement being the degree to which the Holocaust is emphasized. Clearly the Holocaust is pivotal to the creation of modern Israel, but these Al Hanisim versions differ in their calibration of the relationship between these two historical events. Authors also differ on exactly how to describe a contemporary political event using mythically fraught religious language.

How Jewish communities choose to commemorate Yom Ha’atzmaut liturgically — if they choose to do so at all — reflect the archetypes that influence their retelling of the story of Israel’s origins. Just as the Al Hanisim for Hanukkah was not composed until hundreds of years after the events it describes, perhaps we are much too close to the events of 1948 to expect a consensus for how to render these transformative events in liturgical language.

Rabbi Robert Scheinberg is the rabbi of the United Synagogue of Hoboken and teaches liturgy at the Jewish Theological Seminary and the Academy for Jewish Religion. He served on the editorial committees for Mahzor Lev Shalem (2010) and Siddur Lev Shalem (2016), prayerbooks for Conservative Judaism published by the Rabbinical Assembly.