Rachel is the medieval name given to the wife of Rabbi Akiva in the late de-Rabbi Nathan version A (chapter 6). In none of the older sources is a name attached to this woman, although she was well-known.

Rabbi Akiva’s wife is mentioned in three separate sources. While these tell different stories about her, they agree on two details, which may represent the historical core behind the woman. All sources — The Babylonian , The Jerusalem Talmud and Avot de-Rabbi Nathan — agree that Rabbi Akiva’s wife was in some way instrumental in her husband’s rise to prominence. He began his life as a pauper and through her agency became learned and rich. In addition, all the sources know that her husband rewarded her for her troubles with a glamorous headdress usually identified as a golden city, or a golden Jerusalem (see also 59a–b).

Aside from these two details, the sources tell different stories about how Akiva’s wife helped her husband, and in some details contradict one another. Thus the Babylonian Talmud relates that Rabbi Akiva was a shepherd employed by the rich Jerusalem magnate Ben Kalba Savu’a. His daughter saw Akiva, recognized his hidden qualities and proposed to him on condition that he go and study. This resulted in her father’s disowning her. Disowned by her father and deserted by her husband, Akiva’s wife was left to fend for herself for twenty-four years, until finally her husband returned in glory and recognized his wife’s role in his success, saying to his disciples: “Mine and yours are hers.”

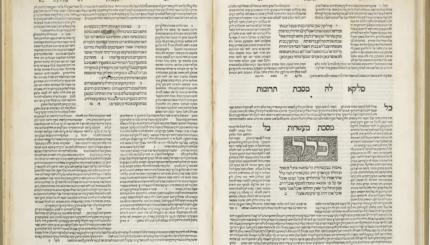

This story, told twice in the Babylonian Talmud, seems to contradict itself in some details. In one of the versions Akiva’s studies are presented as a condition without the fulfillment of which no marriage will take place (Ketubot 62b). Thus Akiva goes off to study after betrothal, but without consummation. In the other version (Nedarim 50a) Akiva sets out on his studies only after the couple has lived in poverty for some time.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In any case, both versions contradict the stories of Akiva’s wife told in the Jerusalem Talmud and in Avot de-Rabbi Nathan and pose chronological complications. If Rabbi Akiva died a martyr’s death in the aftermath of the Bar Kochba revolt (135 C.E.), it is not very likely that he was an employee of the Jerusalem millionaire of 66 C.E., who, according to legend, could supply the city with food for twenty years but lost all his riches when armed bands burnt the food supplies in besieged Jerusalem (Gittin 56a).

Thus one should conclude that the Babylonian Talmud story is legendary and was composed for didactic purposes, primarily in order to justify husbands in Babylonia leaving their wives at home for protracted periods of time in order to study Torah. Perhaps the true father of Akiva’s wife was a certain Joshua, whose son, Rabbi Yohanan, is described in one source as “Rabbi Johanan, son of Joshua, Rabbi Akiva’s father-in-law” (Mishnah Yadaim 3:5). Rabbi Akiva’s son was certainly called Joshua (Tosefta, Ketubot 4:7), probably after his grandfather.

In the Jerusalem Talmud, a completely different story is related about the help Akiva’s wife rendered her husband. According to this version, she sold her hair and thus supplied him with the funds for his study. Apparently women’s hair was a real commodity and could become a source of income for women at the time (e.g. Mishnah Arakhin 1:4) but women’s selling their hair is a very common and also an ancient literary motif (see the apocryphal Testament of Job 23:7–10). Furthermore, the story of the sale of hair serves the literary strategy of measure for measure. Akiva’s wife sold her hair in order to assist her husband, and he later rewarded her with a magnificent headdress.

The Jerusalem Talmud version, which tells of the economic assistance that Rabbi Akiva’s wife rendered her husband, does not involve the husband’s long absence from home. In this it disagrees with the Babylonian Talmud version. The third version of the story, found in the two editions of Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, seems to reject the stories of both the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud. It relates how Rabbi Akiva started off as a pauper and an ignoramus, deciding on his own initiative to go and study. He already had an adult son when he began school. While he was learning he also supported himself economically. Yet the story ends with Rabbi Akiva buying his wife a golden crown; when questioned about the inappropriateness of his actions, he responds by claiming that his wife too had “suffered much with me in the Torah.”

Only in Avot de-Rabbi Nathan version A (the later version of this midrash), is the name Rachel found. It seems to be based on a misreading of the text in Ketubot 62b, where we are informed that Rabbi Akiva’s daughter had acted like her mother with regard to her husband — Simeon Ben Azzai — obviously allowing him to go away on his studies for a lengthy period. This statement is followed by a saying intended to describe the daughter’s actions “the sheep went after the sheep.” The word sheep and the name Rachel are derived from the same root. Avot de-Rabbi Nathan interpreted the saying as naming the woman.

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.