Commentary on Parashat Terumah, Exodus 25:1-27:19; Numbers 28:9-15; Exodus 30:11-16

One of the more enjoyable aspects of my work as a rabbi is studying Torah portions with students becoming bar and bat mitzvah. Not all Torah portions, however, are equally accessible. I was affected by the discussion I had with one of my students who had been assigned Parashat Terumah who wasn’t very happy about it.

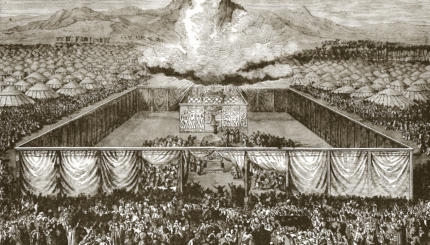

Terumah focuses on the construction of the mishkan, the original desert sanctuary that became the model for the Temple in Jerusalem. The word mishkan derives from the root of the word shakhan, “to dwell,” which is also connected to the word Shekhinah, the Divine Presence. The tabernacle was a place for God’s presence to “dwell” amidst the Israelites for the duration of their desert wanderings. At the beginning of this parashah, God tells Moses to instruct the people of Israel to bring gifts of gold, silver, copper, colorful dyed yarns, fine linen, goat hair, tanned ram skins, what’s usually read as dolphin skin (likely a mistranslation; it was probably a kind of leather), oil, spices and precious stones. Such riches could not be found in the desert; they must have come with the Israelites from Egypt.

The Israelites used these expensive materials to construct the mishkan and its furnishings, including the holy ark overlaid with gold, with a gold cover upon which are placed two cherubim, mythical winged creatures, a golden seven-branched menorah and an altar for sacrifices. The next parashot of Exodus elaborate on other components of the mishkan: an incense altar, a copper washing basin said to be made of the mirrors of the Israelite women and regal clothing for the high priest.

For my student, this all looked like excessive materialism, more so given that it was all offered by poor former slaves in the wilderness. “Why did everything have to be so rich and elaborate?” she asked. The world is burning, the future of the planet unsure, but here we are, talking about an ancient temple built of costly and rare materials.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

We discussed the building of the mishkan as a labor of communal generosity, cooperation and artistry, a place where mutual efforts would invite God to dwell “among,” the Israelites rather than simply “in it.” (Exodus 25:8) She was not completely convinced. Couldn’t you honor God with something simpler? Her questions reminded me of myself as a teen who would prefer a youth group Shabbat in nature over a fancy synagogue interior any day.

Indeed, the mishkan itself hints at the natural world as the ultimate source of beauty and holiness. The menorah is described in botanical terms — with branches, calyxes and petals — leading scholars to conjecture that it was modeled on the shape of the salvia plant. The mishkan incorporated earth (the altar), water (the wash basin), air (incense) and fire (sacrificial offerings). When the mishkan was fully set up, God’s presence filled it in the form of a divine cloud.

The Midrash (Numbers Rabbah 12:13) makes the connection to the natural world even more explicit, connecting different elements of the mishkan to each of the six days of creation. The tent of the mishkan evokes the heavens that God created on the first day; the curtain recalls the separation of the water above and below on the second; the copper basin is compared to the seas created on the third day; the menorah imitates the lights of the heavens that were formed on the fourth day; the winged cherubim are like the birds that took wing on day five; and the high priest is likened to the first human, the crown of creation made on the final day. When the mishkan was finished it was sanctified, just as Shabbat was sanctified on the seventh day after the creation of the world was complete. For our sages, the mishkan was an allusion to the entirety of creation.

After working with my bat mitzvah student, I went on my customary nature walk at a local wildlife preserve. Although it was deep winter, waterfowl abounded and colorful songbirds serenaded from the trees. As I arrived at the half-frozen local lake, it lit up with the warm glow of the setting sun. Dramatic clouds tinged with gold reflected on its mirror-like surface. Here were all the elements of themishkan in a natural form: the shining reflective water, menorah-branched bare trees, heavenly light, glorious clouds and even winged creatures. Just as the mishkan evokes the world, the world evokes the mishkan.

Who would not want to contribute and work to preserve such a holy place? That moment opened a new yet ancient way to think and teach about the mishkan: The Torah’s description of its construction can point to the holiness of our natural world as the ultimate sanctuary, reminding us of our sacred responsibility for its stewardship and care. And the natural world, in turn, brings us back to the Creator.