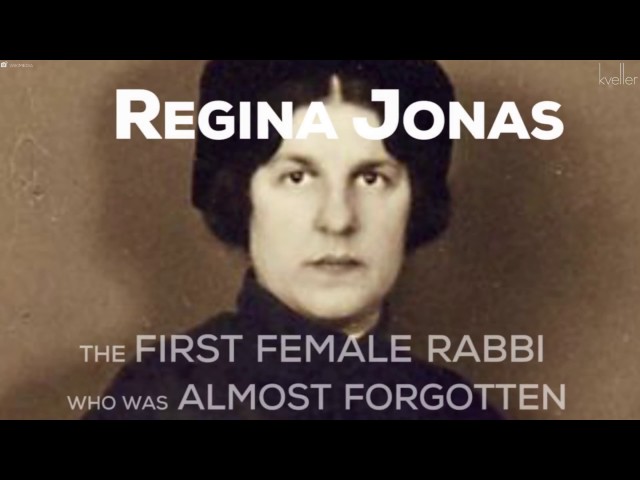

“If I confess what motivated me, a woman, to become a rabbi, two things come to mind. My belief in God’s calling and my love of humans. God planted in our heart skills and a vocation without asking about gender. Therefore, it is the duty of men and women alike to work and create according to the skills given by God.” — Regina Jonas, C.-V.-Zeitung, June 23, 1938.

Regina Jonas, the first woman to be ordained as a rabbi, was killed in Auschwitz in October 1944. From 1942-1944 she performed rabbinical functions in Theresienstadt (also known as Terezin). She would probably have been completely forgotten, had she not left traces both in Theresienstadt and in her native city, Berlin. None of her male colleagues, among them Rabbi Leo Baeck (1873-1956) and the psychoanalyst Viktor Frankl (1905-1997), ever mentioned her after the Holocaust.

In 1972, when Sally Priesand was ordained at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, she was referred to as the “first female rabbi ever” — misinformation which was never corrected by those who knew better. Only when the Berlin Wall came down and the archives in East Germany became accessible was Regina Jonas’ legacy found in the Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden.

In Pre-War Berlin, Yearning to Be a Rabbi

Regina Jonas was born in Berlin on August 3, 1902, the daughter of Wolf and Sara Jonas. She grew up in the Scheunenviertel, a poor, mostly Jewish, neighborhood. Her father, a merchant who died of tuberculosis in 1913, was probably her first teacher. Early on, Regina Jonas felt her rabbinic vocation. Her passion for Jewish history, Bible and Hebrew was apparent even at high school, where fellow pupils recall her talking about becoming a rabbi.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Many people supported Jonas’s interests, among them the Orthodox rabbis Isidor Bleichrode, Felix Singermann and Max Weyl, the last of whom was known for his open attitude regarding religious education for girls. Max Weyl often officiated in the Rykestrasse Synagogue, which Sara Jonas and her two children, Abraham and Regina, regularly attended. Until his deportation to Theresienstadt, Weyl and Jonas met once a week in order to study rabbinic literature — Talmud, Shulchan Aruch, and texts. In 1923, Jonas passed her Abitur at the Oberlyzeum Weissensee. The following year, she attended a teachers’ seminar, enabling her to teach Jewish religion in girls’ schools in Berlin.

In 1924, she matriculated at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, founded in Berlin in 1872. This liberal institution admitted women as students, as did the Jüdisch-Theologisches Seminar in Breslau, founded in 1854, but Jonas was the only woman who hoped to be ordained as a rabbi. All her fellow women students were studying for an academic teacher’s degree.

Making a Halachic Case for Women Rabbis

Eduard Baneth (1855-1930), professor of at the Hochschule and responsible for rabbinic ordination, was the supervisor of Jonas’s final thesis, which dealt with the topic “May a woman hold rabbinic office?” A copy of this document has been preserved and can be found at the Centrum Judaicum in Berlin. Submitted in June 1930, this paper is the first known attempt to find a halachic basis for the ordination of women.

Jonas combines a line of argument with a modern attitude. She did not follow the Reform movement, which was willing to achieve modernization by abandoning . Rather, she wanted to deduce gender equality from the Jewish legal sources: the female rabbinate should be understood as a continuity of tradition. This proves Jonas’s independence both from Orthodoxy, which held equality as incompatible with halacha, and from Reform, which saw itself as the sole advocate of female emancipatory interests.

On the opening page of her thesis, Jonas writes: “I personally love this profession and, if ever possible, I also want to practice it.” On the last page she concludes: “Almost nothing halakhically but prejudice and lack of familiarity stand against women holding rabbinic office.”

Since rabbinic literature did not deal with ordination per se, Jonas embraces the halakhic literature, which relates more generally to women’s issues. She names important women who, though not holding the title “rabbi,” fulfilled rabbinical functions, most specifically as decisors of halakha. In addition to biblical protagonists, she mentions Talmudic personalities such as Beruriah, Yalta, the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra, and also Rashi’s daughters and granddaughters, who were involved in halakhic decision making. She quotes negative Talmudic statements about women, not only countering them with positive statements, but also contextualizing them by quoting equally negative statements about great sages.

Jonas distinguishes between immutable statutes of divine origin on the one hand and “opinions” of individual rabbis on the other. For her, the validity of a prohibition depends on the reasoning behind it, not on the prohibition as such.

A key issue in her argument is the ideal of Tz’ni’ut (Modesty). She expects women in particular to re-establish values such as humility, restraint and morality. In her opinion, a female rabbi should not marry — but every woman should be free to decide if she wants a life as wife and mother or a profession according to her skills. In Jonas’ opinion, women are especially fit to be rabbis, since “female qualities” such as compassion, social skills, psychological intuition and accessibility to the young are essential prerequisites for the rabbinate. Therefore, female rabbis are “a cultural necessity.”

Jonas’ thesis received a grade of “good” (Praedikat gut). Soon thereafter, Eduard Baneth died and his successor, Hanokh Albeck (1890-1972), proved unwilling to ordain a woman. None of the other professors of the Hochschule raised their voices on this issue, probably fearing a scandal. As a result, Regina Jonas graduated only as religious teacher. In the following years, she taught religion at several girls’ schools in Berlin, where she was known to be a very popular and committed teacher.

In 1933, the workload for Jewish teachers increased tremendously, since the students who had to leave public schools due to anti-Semitism not only needed Jewish knowledge, but also needed to learn to be proud of their Jewish heritage.

Achieving Ordination

Nevertheless, Jonas continued to pursue ordination. Finally, in 1935, Rabbi Max Dienemann (1875-1939), executive director of the Liberaler Rabbinerverband (Conference of Liberal Rabbis) agreed to the ordination, on behalf of the Verband. Her diploma of ordination reads: “Since I saw that her heart is with God and Israel, and that she dedicates her soul to her goal, and that she fears God, and that she passed the examination in matters of religious law, I herewith certify that she is qualified to answer questions of religious law and entitled to hold the rabbinic office. And may God protect her and guide her on all her ways.”

Only a few years of rabbinic work in Berlin were granted to Regina Jonas. In 1937, the Berlin Jewish Gemeinde (official community) began to employ her officially as “pastoral-rabbinic counselor” in its welfare institutions. Thereafter she officiated regularly at the Jewish Hospital. Since more and more rabbis were imprisoned or had emigrated, she also started to preach in the more liberal synagogues in Berlin. A group of regulars from the famous Neue Synagoge, the flagship of German Jewry, had her preach at Havdalah services in the “weekday” synagogue. Jonas lectured to groups of WIZO and the Jüdischer Frauenbund, as well as to sisterhoods of the Jewish lodges.

She herself put a strong emphasis on her pastoral work, visiting the sick in the Jewish Hospital and caring for those elderly whose economic situation became desperate after the pogrom of November 9-10, 1938 (“Kristallnacht“). Among her papers, there are many letters from abroad in which refugees thank her for taking care of their parents who had remained in Germany.

In the winter of 1940-1941, the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (the compulsory umbrella organization of German Jewry established by the Nazis in 1939) sent her to several cities where the Jewish Gemeinde remained without rabbis. She gave sermons in Braunschweig, Göttingen, Frankfurt am Oder, Wolfenbüttel and Bremen.

In 1941, when most of those who had so far escaped deportation had to do forced labor and were therefore unable to attend regular services, the congregation instituted special services. Jonas, who was herself forced to work in a factory, led many of these. Survivors report that her sermons and her pastoral work were especially uplifting and encouraging.

Deportation to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz

On November 6, 1942, Regina Jonas and her mother were deported to Theresienstadt (Terezin). Even there she worked as rabbi, preaching and counseling. She was officially part of the Referat für psychische Hygiene, which was led by the psychoanalyst Viktor Frankl.

On October 12, 1944, she and her mother were deported to Auschwitz and probably killed the same day.

In the archives of Terezín there remains a handwritten document that summarizes her religious worldview and her legacy. Under the title “Lectures by the only female rabbi Regina Jonas,” it lists twenty-four topics for lectures, followed by notes on a sermon which she delivered in Terezin. Here she summarizes her religious outlook and testament:

“Our Jewish people was planted by God into history as a blessed nation. ‘Blessed by God’ means to offer blessings, lovingkindness and loyalty, regardless of place and situation. Humility before God, selfless love for His creatures, sustain the world. It is Israel’s task to build these pillars of the world– man and woman, woman and man alike have taken this upon themselves in Jewish loyalty. Our work in Theresienstadt, serious and full of trials as it is, also serves this end: to be God’s servants and as such to move from earthly spheres to eternal ones. May all our work be a blessing for Israel’s future (and the future of humanity) … Upright ‘Jewish men’ and ‘brave, noble women’ were always the sustainers of our people. May we be found worthy by God to be numbered in the circle of these women and men … The reward of a is the recognition of the great deed by God. Rabbi Regina Jonas, formerly of Berlin.”

Reprinted from the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women with permission of the author and the Jewish Women’s Archive.