Recently, we learned that while a woman who commits adultery is ordinarily strangled (if she was married) or stoned (if she was betrothed), an adulteress who is a bat kohen, the daughter of a priest, is executed by fire. In a mishnah on today’s daf, we learn the surprising details of how seraifa, or burning, is carried out.

The mitzvah of those who are burned: They submerge the condemned in dung up to his knees, and they place a rough scarf within a soft one, and wrap these scarves around his neck. This one pulls the scarf toward himself, and that one pulls it toward himself, until the condemned one is forced to open his mouth. And another person then lights the wick and throws it into his mouth, and it goes down into his intestines and burns his intestines.

As with the process we learned for stoning, this method of execution by fire does not fit with the image most people likely conjure up (think Joan of Arc, or Salem witches being burned at the stake). The process described here is both swifter and less visually grotesque. The condemned person is immobilized and forced to open their mouth, then made to swallow fire — clarified in the Gemara to be not a piece of burning wood, but molten lead — which scorches their internal organs.

The mishnah addresses this dissonance by acknowledging a case in which a more traditional burning took place:

Rabbi Elazar ben Tzadok said: An incident occurred with regard to a certain priest’s daughter who committed adultery, and they wrapped her in bundles of branches and burned her. The sages said to him: They did so because the court at that time was not proficient in halakhah.

Rabbi Elazar ben Tzadok records that there was, in fact, a court that interpreted execution by burning in its more obvious sense. The mishnah thereby acknowledges that the practice it outlines is not intuitive, while still affirming it is the correct procedure.

The Gemara asks how the rabbis arrived at this unexpected method of burning, and presents two different but similar derivations:

From where do we derive that burning is like this? It is derived from a verbal analogy between the burning that is described in detailing capital punishment and the burning described with regard to the assembly of Korah. Just as there, they were killed by the burning of the soul but the body itself remained intact, so too here the condemned one is executed by the burning of the soul but the body remains intact.

Rabbi Elazar says: It is derived from a verbal analogy between the burning that is described in this context and the burning that is described with regard to the sons of Aaron. Just as there, Nadav and Avihu were killed by the burning of the soul but the body remained intact, so too here the execution is carried out by the burning of the soul but the body remains intact.

To understand the reason for this method of burning, the rabbis turn to examples in the Hebrew Bible in which God executed people with fire. In the cases of Aaron’s sons, who brought a strange fire before God, Leviticus 10:2 relates: “And a fire went forth from the Lord and consumed them, thus they died before the Lord.” Nearly identical language is used of Korah and his assembly (Numbers 16:35). Midrashim on this line state that the fire consumed them, but not their clothing — i.e., it left their bodies and clothes intact. Later on the daf the rabbis learn the same principle from the end of the verse in Leviticus, that they “died before the Lord,” suggesting their death looked similar to a natural death. This prompts the rabbis to similarly prescribe a method of execution by fire that will not disfigure the body — or even damage the clothing worn by the condemned.

Beyond the instinct to imitate divine methods, the rabbis themselves (as we have seen already) have a strong preference for not prolonging pain and not disfiguring the bodies of the dead. That’s why, for instance, people who are stoned are dropped from a platform at a height that is high enough it has potential to cause mortal injury and low enough that it will not overly disfigure the body. It’s hard to imagine a more gruesome image than that of a person burned at the stake. And we know from the horrifying story of the martyrdom of Haninah ben Teradion, who was executed by the Romans with fire, that external burning is both extremely painful and excruciatingly protracted. All of this may have contributed to the rabbis choosing an alternative that would accomplish the job quickly and leave the body intact and not disgraced.

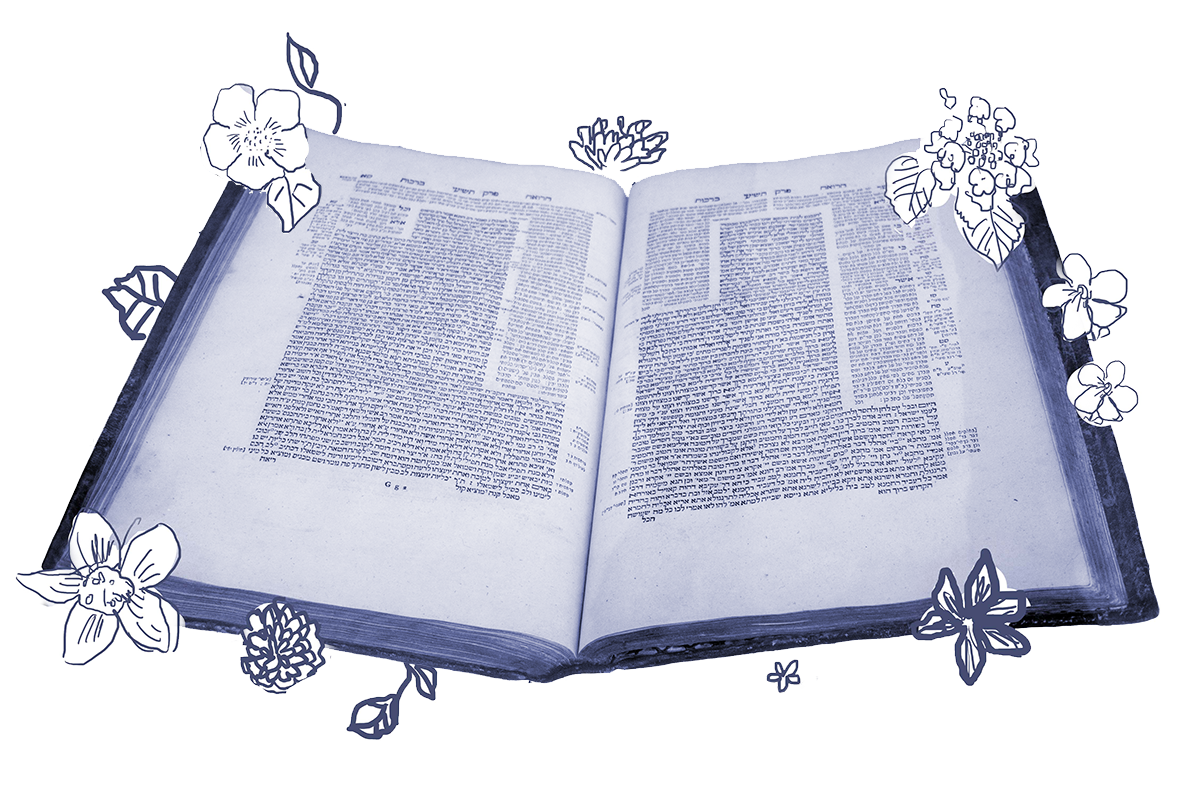

Read all of Sanhedrin 52 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on February 7, 2025. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.