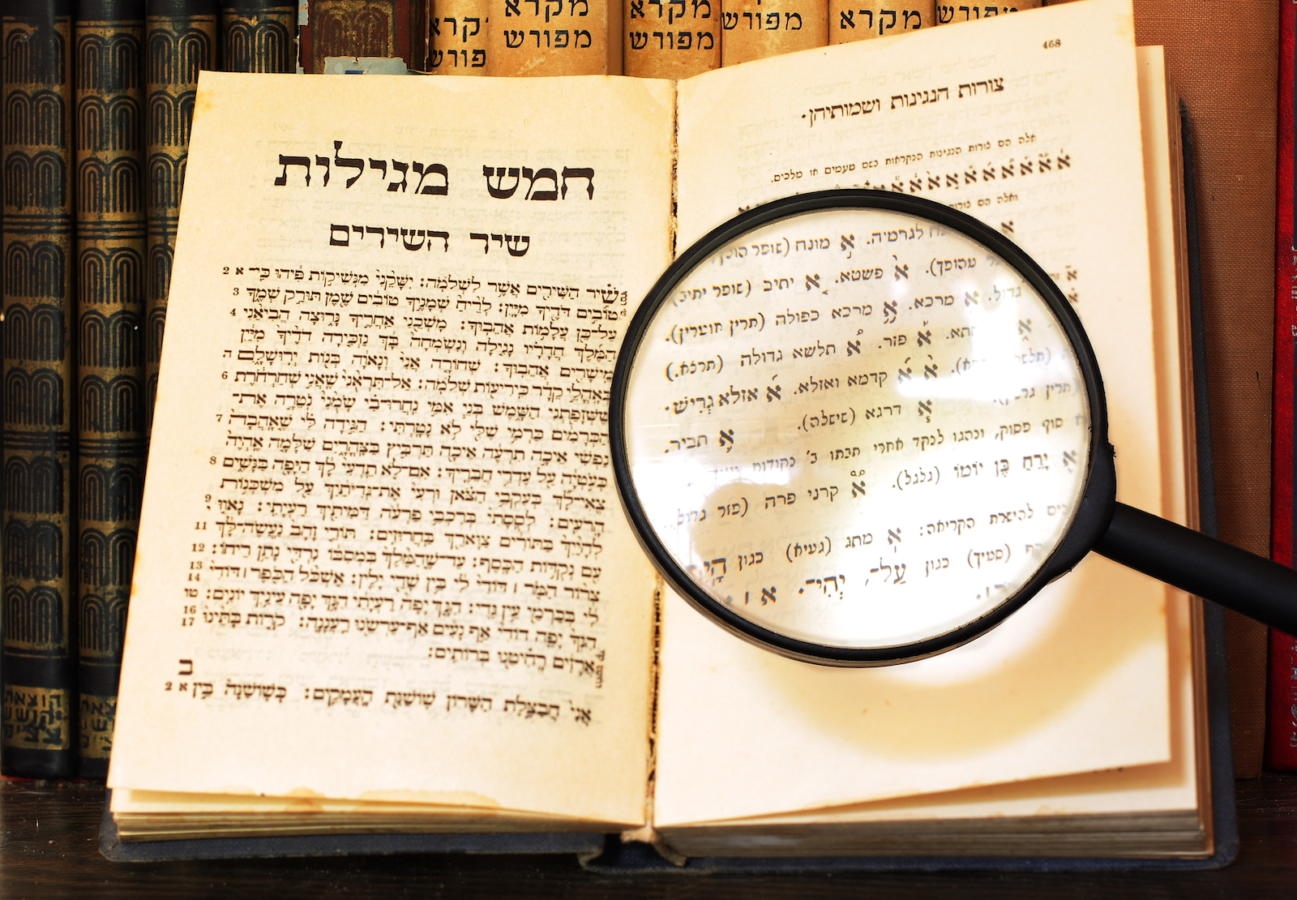

The biblical book Song of Songs — sometimes called Canticles in Christian literature and also known as the Song of Solomon — is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, known as Ketuvim (or Writings). It is eight chapters long and is among the five megillot (scrolls) in the Bible, probably because of its relatively short length.

The rabbis say that Song of Songs is about the relationship between humans and God, which is why they elected to include it in the biblical canon. But Song of Songs is plainly an erotic love poem between two people.

“On my bed at night, I sought the one I love,” the third chapter opens.

“I rose to open up for my lover,” reads another verse.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

And another — “Rise up, my love, my fair one, and come away for, lo, the winter’s past, and the rain is gone” — was popularized by the folk singer Debbie Friedman.

Perhaps the rabbis who included the Song of Songs in the biblical canon were communicating something both to the masses who appreciated its physicality, as well as those who sought something spiritual, even metaphysical. Judaism has always considered the body to be sacred and all acts associated with it to be holy, no matter how mundane. How much more so does it consider the intimacy shared by two lovers to be among the most elevated of physical acts.

Even as we recognize the tension between the plain meaning of Song of Songs and the way both biblical scholars and classical commentators parse the text, it ought to be our goal as contemporary Jews to hold both loving relationships in mind: the erotically human and the divinely inspired. They do not pose a conflict. In fact, one enhances our understanding of the other. As Rabbi Harold Schulweis, a prominent Conservative rabbi of the last century, once quipped, “Either/or questions are not good for the Jewish people.” In the case of Song of Songs and the relationships described therein — both human and divine — both/and seems a more appropriate frame.

Because King Solomon is considered in many sources to be a lover — note his relationship with the Queen of Sheba, for example — Jewish tradition assigns authorship of the book to his younger, more virile self. This claim is highly suspect, but attributing the text to a popular king of Israel, irrespective of his flaws, certainly gives the text more credibility in the eyes of the rabbis. Were its authorship assigned to an unknown writer, it would have made its inclusion in the Hebrew scriptures more controversial.

Rabbi Eugene Borowitz, a leading liberal Jewish theologian of the late 20th century, taught that all loving relationships should mirror the relationship of the individual striving for the divine — what he called a covenantal relationship, similar to what the theologian Martin Buber called an I-Thou relationship. One love leads us to the other. Love indeed leads us to the Other.

Jewish rituals — the mitzvot, or commandments — at their best help to mitigate the distance that separates us from one another and from God. But while the rabbis derive mitzvot from various Torah passages, Song of Songs stands alone in its pure expression of love. Most Jewish liturgy is highly intellectualized and often eclipses such pure expressions of love. Song of Songs reminds us that love is the fount of all relationships — including and especially with God.

Like the love that is described in it, and the love that so many of us are blessed to know, Song of Songs is not a static work. It is a dynamic text, as is our relationship with it. Each time we enter its pages, we become the lovers described in it and are embedded in their relationship. We become part of their love and share in it. When we take leave of the text, a bit of it is left in us and we leave a bit of ourselves in the text. As a result, we are changed and so is Song of Songs.

There are two reasons why Song of Songs was assigned by the rabbis to be read during the spring holiday of Passover. On a practical level, the rabbis wanted to include as much biblical text as possible in holiday celebrations throughout the year. This is something Passover shares with the other Jewish festivals.

But there’s something particularly fitting about reading Song of Songs on Passover. It was in the desert wandering after the exodus from Egypt that the loving relationship between God and the Jewish people was born. Moreover, after a long winter, as the spring flowers blossom and the buds burst into bloom, one’s thoughts often turn to love and longing. What better way to freely express human love than in the guise of the relationship with the divine.

According to Jewish tradition, Song of Songs is one of ten songs of praise sung to the creator by biblical characters. This song, sung by King Solomon, is next to the last in the series and precedes the final song, which is to be sung by Jewish exiles returning to the land of Israel during the messianic period.

We can conclude from this that it is the physical love between two human beings that has the potential to redeem the human soul, especially when it mirrors the love between the individual and God. When such love fills the world, the possibility of messianic redemption is at its greatest. It is only love that will ameliorate the hate in this world.

Rabbi Abraham Kook, the first chief rabbi of Israel, called such love ahavat chinam (unconditional love) as a counterbalance to the sinat chinam (baseless hatred) to which our sages attribute the destruction of the ancient temples. Thus it is human love — reflected in the physical relationship between two individuals and which is celebrated in Song of Songs — that will precede world redemption.