Although few people in the contemporary era equate Jews with the world of sports, Jewish Americans have a long and rich history in amateur and professional athletics. Sports provided Jewish immigrants with an opportunity to feel “Americanized” and express their ethnic pride. Because of the broad popularity of athletics among diverse sectors of the American public, success in the field gave Jews a measure of social status and respect. Through their involvement in a common American experience, Jews helped allay notions that they were alien and undesirable without sacrificing their Jewish identity or their importance to the Jewish community at large.

Modern sports evolved in the United States in the 19th century, and the religiously liberal, upwardly mobile German Jews viewed involvement in organized athletics as a means of gaining stature and recognition. The wealthiest of this group, such as August Belmont, bought race horses, while others purchased teams in the new and evolving sport of baseball. This generation of immigrants established the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) in 1874, aimed at emulating the Christian YMCA in using sports and recreational activities to improve the moral, social, and educational life of young German Jews.

Countering “Softness”

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed both a flood of new Jewish immigrants into American cities and an increasing symbolic attachment to encouraging athletic prowess for the nation as a whole and especially for young American males. At a time when massive urbanization and immigration drastically altered the composition and demographics of the country, many Protestant reformers expressed anxiety about the decline of the virtuous values associated with the rural frontier. They bemoaned the “softness” and “complacency” associated with the development of modern society. The Jewish voice urging involvement in sports was loudest among the most assimilated and successful sectors of the German Jewish community, who viewed it as a core component of acculturation.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Although the YMHA as an institution continued to serve German Jews, its programs increasingly sought to teach Eastern European newcomers what it considered to be the necessary components of Americanization. For its leaders, athletics and morality went hand in hand. Jewish institutions such as the YMHA and the Educational Alliance embraced the belief that participation in sports was an important method of easing the transition from immigrant to American. Both Jewish and non-Jewish reformers sought to develop organized sports clubs and athletic associations as a means of developing “teamwork” and “cooperation” skills among these new immigrants.

Progressive Era reformers viewed team sports as a tool to prevent vice and delinquency among youth by moving them out of the streets and into supervised spaces such as gymnasiums, playgrounds, and ball fields. In 1911, Julia Richman recommended to the Committee on Education of the Educational Alliance that the gym be opened on certain afternoons for “girls between the ages of 11 and 15, who are wandering aimlessly about the streets and who might be attracted to amusement halls and other places of dubious influence.”

The Jewish Sporting Scene

German Jews, already defensive about the possibility of increased anti-Semitism brought on by the arrival of their poor and working class immigrant brethren hoped that promoting athletic achievement would re flute the arguments that the Jews were a weak and alien race whose people historically eschewed physical endeavors in favor of religious and intellectual study.

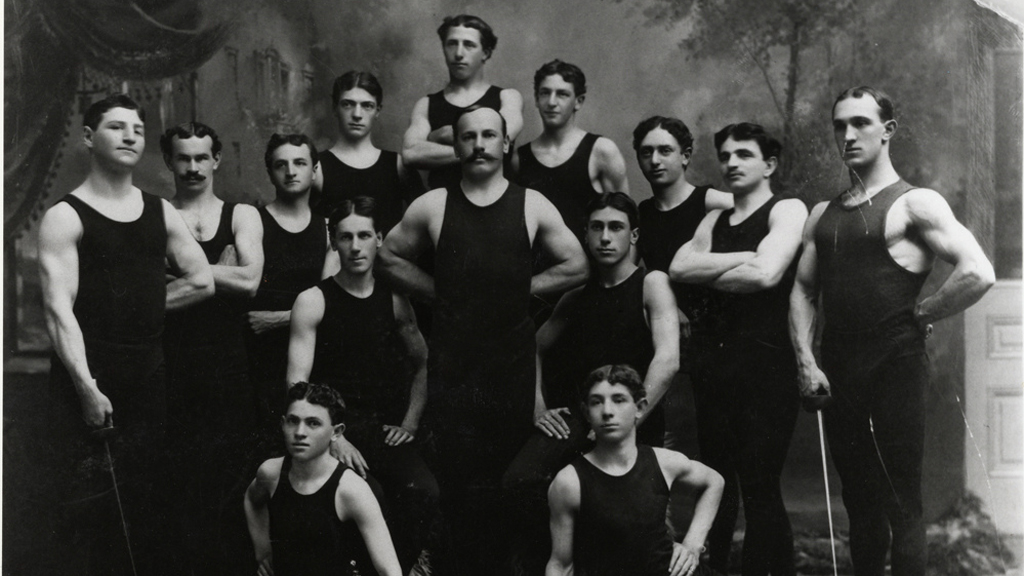

In New York City, the center of immigrant Jewish culture, the YMHA established the Atlas Athletic Club in 1898 with the stated goal of cultivating elite Jewish athletes and helping them gain recognition at a time when other similar clubs were closed to them. William Mitchell, the YMHA superintendent, stressed that Atlas members should strive for the highest goals in sports, and he declared that he hoped “some day to see some of our own boys take a prominent part in athletic competition and thus disprove that our own people do not give proper attention to physical development.”

Even more than the settlement houses or Jewish community centers, the YMHA–which moved to 92nd Street and became known as the 92nd Street Y in 1901–was successful in attracting young Jewish men from the Lower East Sid to its gymnasium programs. In its first year in the larger building, more people participated in the Y sports programs than any other single endeavor. In 1904, the Y added a varsity basketball squad to its burgeoning intramural sports programs, which competed against settlement house teams and against other YMHAs and YMCAs throughout the East Coast, and after 1912, within what became known as the Metropolitan YMHA league. A similar proliferation sports activity took place in other cities with significant but smaller Jewish communities, including Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, Providence, Detroit, Los Angeles, and, especially, Chicago.

Sports for Women

Although athletic pursuit was frequently framed as a male activity, settlement house workers also sought to promote physical exercise, recreation, and participation in sports for working-class Jewish immigrants in their girls clubs. Likewise, the establishment of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA) created athletic opportunities for Jewish girls. They held classes in gymnastics, swimming, basketball, and dancing.

The ideology of sports and physical fitness for female immigrants served to reinforce gender divisions in American society. Many Progressive Era reformers explicitly stated that these poor and working-class women needed physical exercise to fulfill domestic roles and to offset the negative influence of unsanitary urban conditions. At the Educational Alliance, female gender-appropriate physical fitness emphasized “health-building” sports rather than competition. At the same time, Jewish organizations promoted women’s basketball in intramural and club leagues, with the YWHA’s touting the sport as the greatest of indoor games, while at Chicago’s Jewish Peoples’ Institute, girls basketball teams won three championships.

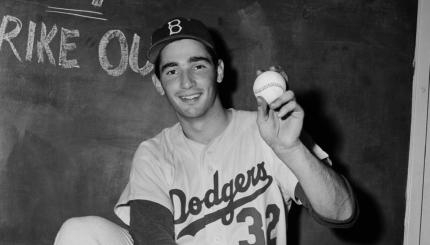

During these pivotal early years of the 20th century, the Jewish press–catering to an Eastern European immigrant population–stressed the importance of developing Jewish athletes. In 1909 the Chicago-based Yiddish language Jewish Messenger wrote that the Jew “has left behind… lands of oppression” and in the “free country” of America “desires to improve his physical equipment to meet adequately the demands of the strenuous life.” In the following decades, Jewish athletes would respond to this call by carving out an important place for themselves in the American scene.

Reprinted with permission from the American Jewish Desk Reference (The Philip Lief Group).