Job is one of three books in the Bible which, collectively, are known as the Wisdom Literature. (The other two are Proverbs and Ecclesiastes.) Unlike the other books of the Bible which deal more specifically with the Jewish people, these deal with universal questions about justice, piety and the nature of the universe. In fact, neither Job nor any of the other characters in the book are identified as Jewish.

While Proverbs gives a rather sunny perspective that the universe is pretty well ordered and goodness is rewarded while sinfulness is punished, Ecclesiastes and, most especially, Job complicates that picture. Of the three, Job is the darkest — facing head on the problem of undeserved suffering.

Job has a short narrative frame written in prose, and in the middle is a long poetic dialogue between Job and his friends which concludes with God coming down to earth to speak to Job. Here is a section-by-section summary:

Narrative Prologue (Job 1–2)

As the book opens, God is holding court in heaven and points approvingly to Job as an example of a righteous person. Satan, who functions in this book as part of the heavenly court, challenges God’s premise: Perhaps if Job were not so fortunate (wealthy, the father of ten healthy children), he would not be quite so pious. God proposes an experiment to prove Job’s loyalty: Satan may take everything from Job — his health, his wealth and his family — except his life. God is confident that Job will still be a loyal servant. Satan takes the bet.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

In the next chapters, Job rapidly loses everything: first his flocks, then his children and finally his health (he is stricken with a skin disease). His wife suggests that he should curse God in order to bring death upon himself. But Job refuses, and continues to praise God. Three of his friends come to comfort him and they sit together in silence.

Three Cycles of Speech with Three Friends (Job 3–37)

In this section of Job, the language switches from prose to poetry. Here, Job and his friends (Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar) engage in a long conversation attempting to make sense of his suffering. It begins with Job bewailing his unfortunate fate and cursing the day he was born. At first the friends try to comfort him, but then they wonder aloud if he hasn’t done something awful to merit this severe punishment. They cannot relinquish their fundamental worldview that the world is ordered by a just God and that people receive pain or reward in proportion to their deeds. Their words of “comfort” turn to words of accusation and become increasingly more painful to Job. Yet Job never wavers, staunchly maintaining his innocence. This part is structured as three cycles of speech between Job and his friends. When they all seem spent, another character not previously mentioned, Elihu, comes forward — he too ends up scolding Job.

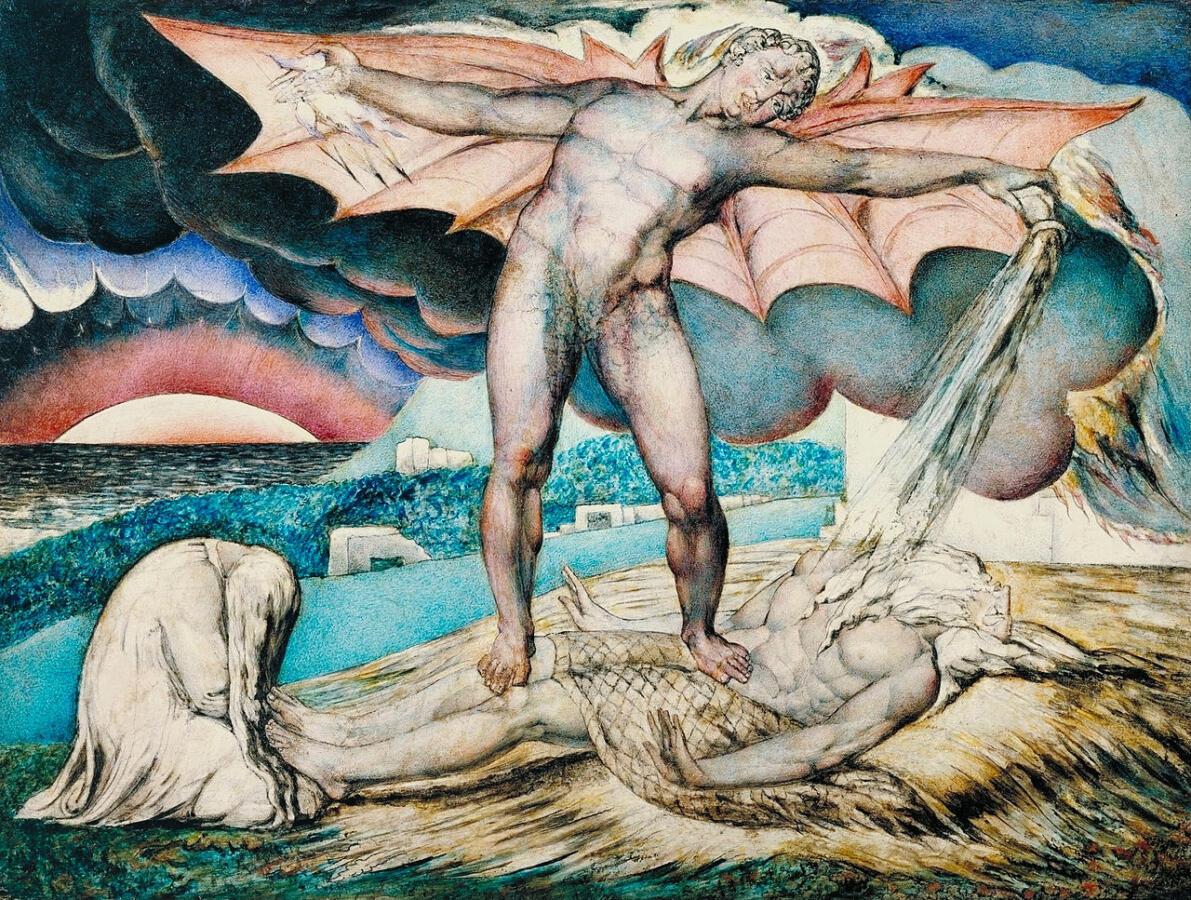

Theophany (Job 38–41)

As the very long dialogue between Job and his would-be comforters (turned accusers) becomes increasingly frustrating and painful, Job stops seeking satisfaction from his friends. Instead, he demands it directly from God. Remarkably, God answers, the divine voice booming down from a storm cloud. God describes the stunning complexity of the world, whose operations are far too difficult for a human to understand.

Have you ever commanded the day to break?

Assigned the dawn its place? …

Have you penetrated to the sources of the sea,

Have the gates of death been disclosed to you?…

Have you surveyed the expanses of the earth?

Job 38:12–18

God describes the complexity and majesty of the whole world, and then also the terrible primordial beasts that stalk it, the Behemoth and the Leviathan. The substance of the message is essentially this: I command a world of stunning complexity. Who are you to question me?

Of course, God’s reply is not a satisfying answer to Job’s charge — after all, he’s still innocent — but it elicits a clear response: Job is humbled. He replies:

Indeed, I spoke without understanding

Of things beyond me, which I did not know…

Therefore, I recant and relent,

Being but dust and ashes.

Job 42:3–6

Concluding Narrative (Job 42)

Having answered Job out of the whirlwind and seen that he is humbled, God now turns sharp words on Job’s friends, and accuses them of speaking wrongly, unlike Job. God tells them that they should ask Job to pray on their behalf. Job, meanwhile, is restored. He is granted double his original wealth and ten healthy children. Job lives the rest of his days in peace until he dies at a ripe old age.

The story of Job has fascinated for millennia. For one, it challenges God’s justice like few works of literature before or since, expressing the problem of undeserved suffering as eloquently as any work in history (to boot, the language is rich — on par with Shakespeare and other great works). For another, it is full of surprising twists and turns. We don’t expect God to be goaded into a bet with Satan, but he is. We don’t expect Job to be pious in response to his devastation, but he is. We expect Job’s friends to comfort him, but they don’t. We don’t expect God to answer Job’s charge like a defendant forced into the courtroom, but he does. We don’t expect Job to be made whole, but ultimately he is. For this and many other reasons, Job isn’t just a jewel of the Hebrew Bible, but a true classic of world literature that has inspired interpretation and reinterpretation in antiquity and today.