The has consistently defied attempts to categorize it. The legalistic nature of many of its discussions, as well as its importance for the later development of Jewish law, have led many to describe the Talmud as a code of law. However, this narrow definition fails to account for the stories, theological discussions, and anecdotes that make up much of the text. Furthermore, we cannot ignore the structural differences between the Talmud and other Jewish and non-Jewish law codes.

Codes of law, which are designed for easy reference, generally follow a clear order and offer concise rulings. In contrast, the Talmud text includes minority opinions, digresses from its intended subject, and leaves cases unresolved. In more than 300 cases, the Talmud concludes a discussion with the word teyku—a declaration that the issue is unresolved and (as later tradition understands the term) will not be decided until the messianic age.

Theory, Not Code

Without attempting my own, necessarily flawed, definition of Talmud, I will suggest that the legal interests of the Talmud tend primarily toward the development of a Jewish legal theory–and not toward the codification of a body of law. The Talmud is concerned primarily with the process of determining a law or a legal principle, and not in the law itself. To understand this interest, we will examine some of the ways in which the Talmud develops general principles, addresses problematic laws, and reconciles conflicting laws.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

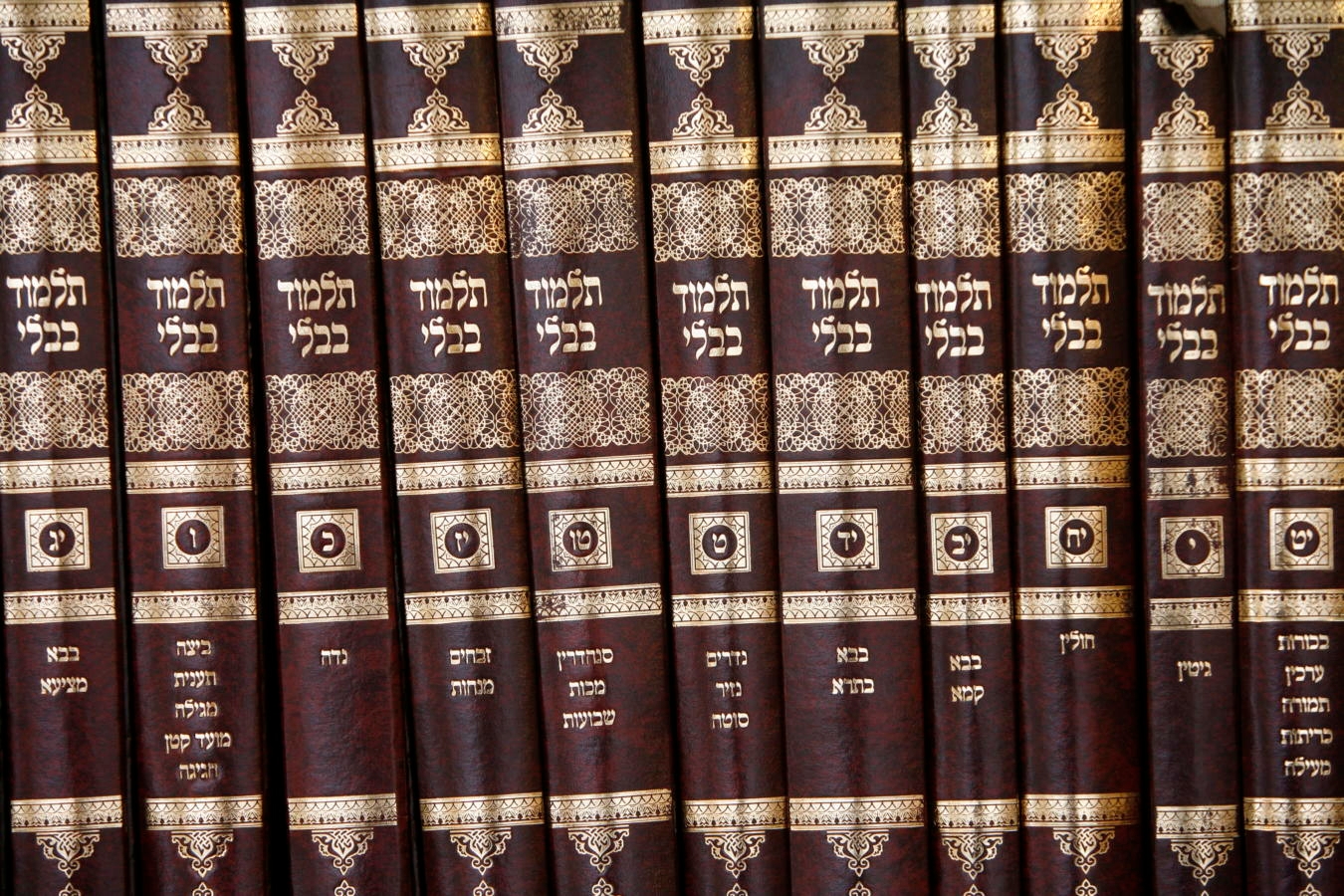

The Talmud is comprised of the , completed around 200 C.E., and the , completed around the sixth or seventh century C.E. The Mishnah, which is written in Hebrew, consists primarily of case law. The text introduces a scenario, then offers one, two or, in rare instances, three rulings on the case at hand. Although an individual chapter of the Mishnah may work through the various details of a legal concept, the Mishnah includes virtually no discussion beyond the presentation of originally opposing opinions, and does not decide between opposing rulings. The Gemara, written primarily in Aramaic, discusses and expands upon the Mishnah, while also offering stories and loosely related discussions.

The Mishnah often details rules relating to specific cases, and then sums up the discussion with a klal—a general principle that can be applied to other cases. For example:

“One who steals wood and makes vessels from it, or one who steals wool and makes clothing from it [upon confessing or being caught] pays [the owner] the cost of the object at the time it was stolen [i.e. the thief pays the cost of the wool, not of the clothing.] One who steals a pregnant cow and it gives birth, or one who steals a ewe in need of shearing pays the cost of a cow about to give birth or of a ewe about to be shorn. One who steals a cow that later becomes pregnant and gives birth, or a ewe that later needs shearing and is shorn pays the cost of the animal at the time it was stolen. This is the klal: all thieves pay the price of the object at the time it is stolen.” (Mishnah Bava Kamma 9:1)

The Mishnah offers a number of specific cases of theft and reparation, but is primarily interested in deriving from these cases a general principle that will serve as a basis for later decisions. Ultimately, the Mishnah may even be less concerned with appropriate fines for theft than with greater questions of property ownership and justice. The klal with which the Mishnah ends suggests that ownership extends only to property under one’s direct control, and that a thief’s intention is the primary determinant of his or her punishment. These principles may, in turn, be applied to other areas of civil and criminal law.

Legal theory cannot exist in a vacuum, but must be refined and revised in response to real life demands. The Talmud constantly balances attention to legal minutiae with a desire to maintain the coherence of the Jewish legal system as a whole. Generally, the Talmud derives specific laws formalistically, through a comparison of sources, interpretation of texts, and inference from previous cases. Many legal discussions are theoretical in tone—only occasionally does the text offer an instance of the law in practice. Some of the most interesting instances of real world interference in the theoretical discussions involve laws that, while technically acceptable according to the rules of legal interpretation, cause difficulties when implemented.

Real World Concerns

In some cases in which a particular law threatens to undermine an entire part of the legal system, the rabbis declare a change in the law “mipnei tikkun ha’olam“—literally, “for the sake of sustaining/repairing the world.” Most of these cases revolve around issues of marriage and divorce and concern procedures that, while legally valid, may create a doubt about a couple’s marital status.

In one such instance, the Mishnah notes that it was once acceptable for a get (divorce document) to identify the divorcing couple by any names by which they were known. According to the Gemara, this practice created problems for couples in which one or both partners used different names in different cities:

“According to Rabbi Yehuda, Shmuel said: The people of a far away place sent the following question to Rabban Gamliel: There are people who come from your city to ours who are named Yosef, but here go by Yochanan; or who are named Yochanan, but here go by Yosef. How are we to write gittin (plural of get) for them? Rabban Gamliel made a takana (a change in the law) that the get must refer to “Mr. so-and-so, and whatever other names he may have” and “Ms. so-and-so, and whatever other names she may have ” for the sake of tikkun ha-olam” (Gittin 34b).

The Gemara expresses a concern that a get that refers to the divorcing couple by one set of names will not be accepted as proof of divorce in a place in which one of the partners goes by a different name. Questions about the legitimacy of the get may discourage remarriage or may raise questions about the status of subsequent marriages and the children of those subsequent marriages. The technicality allowing the use of nicknames or aliases in the get thus threatens the greater institution of marriage. The rabbis therefore sacrifice a theoretically acceptable practice in order to guarantee the sustainability of the system as a whole.

Reality again interferes with the theoretical practice of law in the well-known debate between the schools of Hillel and Shammai, two early authorities, about the proper words to say to a bride. The school of Shammai argues that one should describe the bride “as she is,” while the school of Hillel advocates describing the bride as “beautiful and graceful,” regardless of her appearance. As support for its position, the school of Shammai invokes the biblical injunction to “stay far from an untruth” (Exodus 23:7). Surprisingly, the school of Hillel responds not with an opposing biblical verse, but with an example from everyday life: “If one bought a defective product from the market, would you praise it in front of him or insult it in front of him? We have said that one should praise it.” The Talmud ultimately accepts the position of the school of Hillel. (Ketubot 16b-17a).

While acknowledging the problematic comparison between a bride and a product purchased in the market, we should note the radical nature of the school of Hillel’s claim that everyday experience can trump even biblically-based legal reasoning. When the law, as derived by exegesis and other accepted techniques, proves inconsistent with community norms, the school of Hillel suggests, the law may be abandoned for the sake of preventing an individual’s shame.

The Talmud is often characterized as overly concerned with legal minutiae and with dictating laws for every area of life. As we have seen, the Talmud does pay considerable attention to individual laws, but uses these laws as the basis for deriving legal principles and methods of legal reasoning.

Beneath the technical and detail-oriented discussions of individual laws lie larger questions about legal categories, about the relationship between individual laws and the greater legal system, and about the interplay between the theoretical world of legal reasoning and the concrete world of legal and ethical choice. Law, the Talmud suggests, is an ever-changing negotiation between the whole and its parts, and between theory and practice.