The first “American” Thanksgiving was held in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621, attended by 90 Native Americans and 50 English Pilgrim settlers. That first Thanksgiving mirrored ancient harvest feasts such as Sukkot, the ancient Greek mid-June Thesmophorian celebration, and the ancient Roman Cerealian rites of mid-April.

The Pilgrims’ Thanksgiving was not an annual event, and did not become an American ritual for more than 200 years. To mark the adoption of the Constitution and the establishment of a new government, President George Washington declared Nov. 26, 1789, a day of thanksgiving and prayer. However, Washington did not renew his declaration. It was not until 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln fixed the last Thursday of each November as a “day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father.”

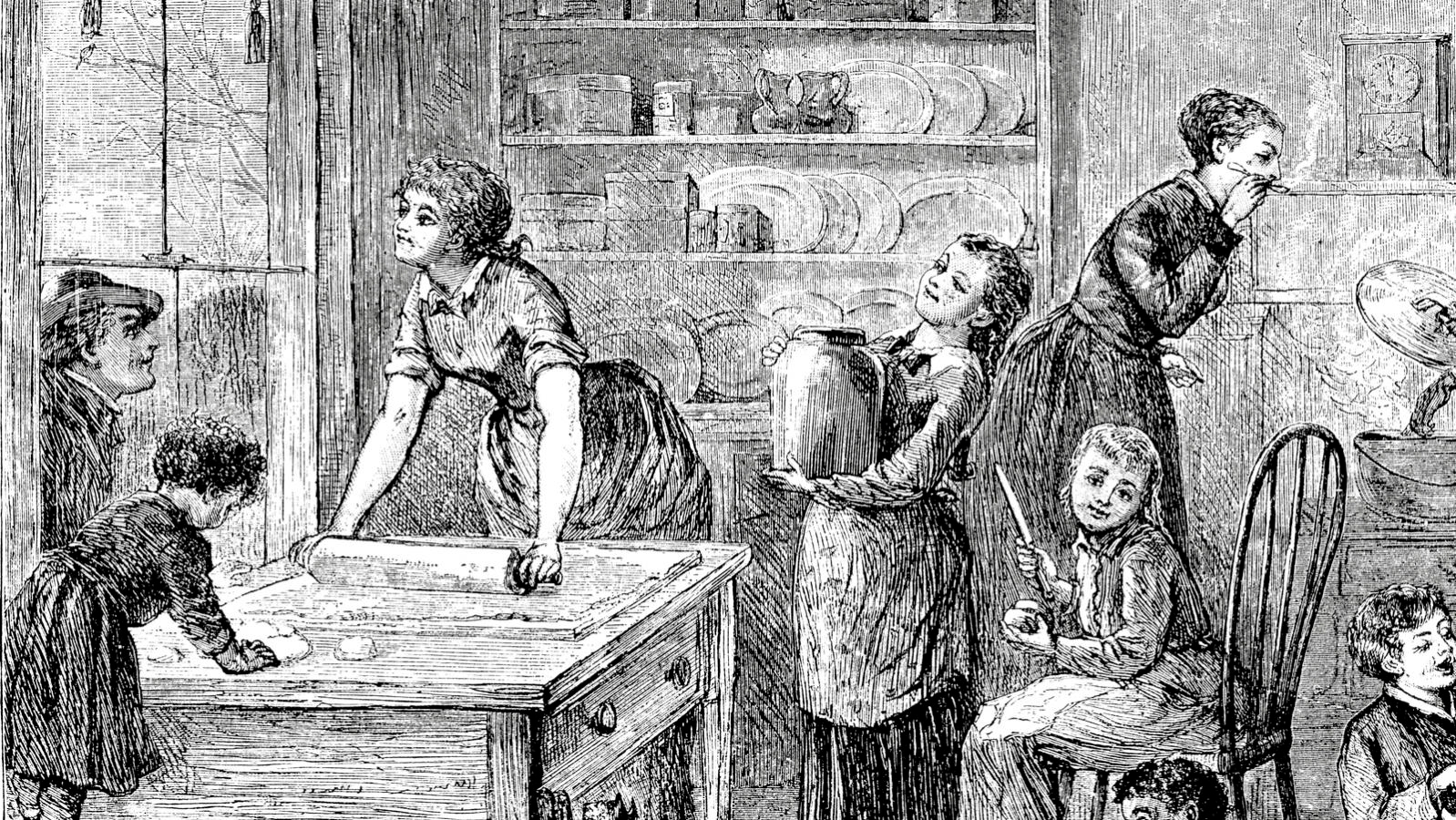

After the Union triumphed, Thanksgiving Day became an even more significant observance in the northern states.

It was in this context that Governor John W. Geary of Pennsylvania, in 1868, issued a proclamation to the citizens of his state urging them to celebrate Thanksgiving. Geary’s proclamation read in part:

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Unto God our Creator we are indebted for life and all its blessings. It therefore becomes us at all times to render unto Him the homage of grateful hearts . . .and I recommend that the people of this Commonwealth on [Nov. 26] refrain from their usual avocations and pursuits, and assemble at their chosen place of worship, to ‘praise the name of God and magnify Him with thanksgiving.

While such sentiments were not offensive, some of Geary’s additional words were: “Let us thank Him with Christian humility for health and prosperity,” Geary urged, and he called on Pennsylvanians to pray that “our paths through life may be directed by the example and instructions of the Redeemer, who died that we might enjoy the blessings which temporarily flow therefrom, and eternal life in the world to come.”

The terms that Geary used roused a unified protest from Philadelphia’s rabbis because in the words of America’s first English-language Jewish newspaper, The Occident, Geary “apparently intended to exclude Israelites” from the celebration. By 1868, Philadelphia’s Jewish population was among the largest in any American city. According to The Occident, a week after Geary’s proclamation the “Hebrew Ministers” of Philadelphia “deemed it their duty” to draft a powerful petition in response. Their “solemn protest” was signed by all seven of the city’s rabbis, including Sabato Morais, who later played a central role in establishing the Conservative movement‘s Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York, and Morris Jastrow, a Reform leader in Philadelphia. Regarding Geary’s choice of words, the rabbis — regardless of their affiliation — agreed that:

An [elected] official, chosen by a large constituency, as the guardian of inalienable rights, ought not to have evinced a spirit of exclusiveness. He should have remembered that the people he governs are not of one mind touching religious dogmas, and that by asking all to pray that ‘their paths through life may be directed by the example and instruction of the Redeemer’ . . . he casts reflections upon thousands, who hold a different creed from that which he avows.

The rabbis were confident that, in his private capacity, Geary would resent being told by a Catholic priest that, on a national holiday, he should go make confession, or that any other public officer might try to tell him what religious observance he must perform. The rabbis observed:

“The freedom-loving authors of the American Constitution opened indiscriminately to all the avenues of greatness, so that the position now filled by a follower of . . . [Protestant theologians] Calvin or Wesley may tomorrow be occupied by the descendant of Abraham, or, perchance, by a free-thinker.”

The rabbis condemned Geary’s proclamation as:

“an encroachment upon the immunities we are entitled to share with all the inhabitants thereof; and we appeal to the sense of justice which animates our fellow-citizens, that a conduct so unwarrantable may receive the rebuke it deserves, being universally stigmatized as an offence against liberty of conscience, unbecoming a public functionary, and derogatory to the honor of the noble state he represents.”

Despite this outspoken rabbinical indictment, Geary did not revoke his proclamation, and Pennsylvania officially celebrated a Christianized Thanksgiving that year. As decades have passed, however, Thanksgiving retains even less of its original English Christian origins — other than the turkey and cranberries consumed by the Pilgrims. Today, signs in the windows of butcher shops in Jewish neighborhoods advertise turkeys for Thanksgiving.

Most of American Jewry has absorbed the holiday, shorn of its Christian trappings, and made it a non-religious time for family gathering. In 1868, Pennsylvania’s rabbis expressed what would become the majority American view: Government-declared holidays should— with the possible exception of Christmas — be totally devoid of religious content and that each individual may bring to it whatever, if any, spirituality he or she wishes.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.