The “Twelve Minor Prophets” is the eighth and last “book” in the second section of the Hebrew Bible, the Nevi’im, or Prophets. It is, as its name implies, not a unified whole but a collection of 12 independent books, by (at least) 12 different prophets.

“Minor” refers not to their importance but to their length: All were considered important enough to enter the Hebrew Bible, but none was long enough to form an independent book. One of these, Obadiah, is only a single chapter long, and the longest (Hosea and Zechariah) are each 14 chapters. They range in time from Hosea and Amos, both of whom date to the middle of the eighth century B.C.E. ,to parts of the books of Zechariah and Malachi, which are probably from the beginning of the fourth century B.C.E.

One theme that unifies the 12 prophets is Israel’s relationship with God. What does God demand of humans? How do historical events signify God’s word? These are questions that appear throughout Biblical prophecy. But nowhere in the Bible does a single book present as wide a variety of views on these subjects as does the collection of the Twelve Minor Prophets. Even within a single time period, there is a remarkable diversity of views.

Hosea and Amos

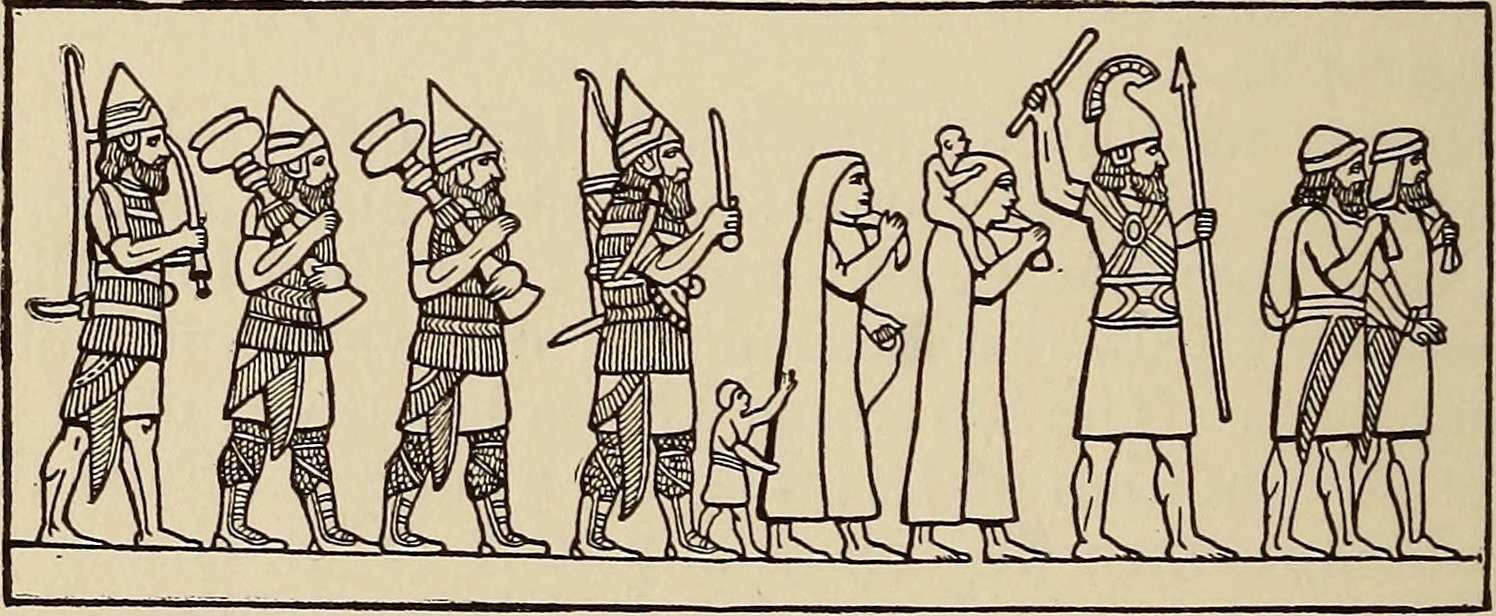

Both Hosea and Amos were composed in the second half of the eighth century, in the Northern Kingdom of Israel. The king of Israel from approximately 790 to 750 B.C.E. was Jeroboam II (son of Joash), who built Israel into a wealthy trading empire by controlling the trade routes to Damascus on both sides of the Jordan. In response to this, Amos focused in his prophecies on the economic disparities created by Israel’s newfound wealth, criticizing the wealthy Israelites’ lack of concern for the fate of the poor. He castigated those who “lie on beds of ivory, sprawled on their couches, eating the fattest of sheep and cattle from the stalls who drink from wine bowls, and anoint themselves with the choicest oils, but are not concerned about the ruin of (the House of) Joseph.” (Amos 6:4-6). (“Joseph” is one term used to refer to the Northern Kingdom.)

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In contrast, Hosea focused on the theme of Israel’s loyalty to God. The new wealth and new openness to foreign trade created, in Hosea’s view, other forces threatening Israel’s exclusive loyalty to God. One such force is the influence of Assyria: “Ephraim (i.e. the Kingdom of Israel, centered around the inheritance of the tribe of Ephraim) went to Assyria and sent embassies to the “great king,” but he cannot heal you, nor can he remove your hurt.” (Hosea 5:13) Hosea describes God as longing for the day when Israel will declare “Let us return to God, for He attacked us but will heal us, smote us, but will bandage us…we will know, no, rather we will run quickly to know God” (Hosea 6:1-3).

Micah

The next of the Minor Prophets, working historically, was Micah, who prophesied at the end of the eighth century in Judah, the Southern Kingdom. He was active at the same time as Isaiah, whose prophecies are recorded in first part of the long Biblical book bearing this name. During this time period, the Assyrian empire threatened to conquer Judah, and here we encounter a difference of views and emphases between prophets of the same period. Micah was a practical and national thinker; Isaiah had a more universal vision. Whereas Isaiah’s vision of the End of Days is universal, ending with the famous sentence “Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isaiah 2:4), Micah adopts but changes this vision, adding two sentences that focus particularly on the nation of Judah: “Each man shall sit under his vine and under his fig tree, with no one to make him afraid, for thus has the mouth of the Lord God of Hosts spoken. For though all the nations will go in the name of their individual god, we will walk in the name of the Lord our God forever” (Micah 4:4-5).

Obadiah, Nahum Habakkuk, & Zephaniah

The next of the Twelve Prophets are Obadiah, Nahum, Habakkuk (especially chapters 1-2) and Zephaniah, all of whom prophesied around the time of the destruction of Judah, at the end of the seventh and beginning of the sixth centuries. Despite the fact that they all

prophesied in the same period, they hone in on different issues. Zephaniah refers to idolatry and corruption in Jerusalem, describing the punishment of the impending “day of the Lord” (Zephaniah 1:7). Nahum’s prophecy speaks about the fall of Nineveh,which was conquered by the Babylonians in 612 BCE. Habakkuk focused on the social injustice in Judah and announced its destruction at the hands of the Babylonians. “Behold, I bring up upon you the Chaldeans (a term often used to refer to the tribes in southern Babylonia), a bitter and furious people, going to the ends of the earth to take over others’ habitations” (Habakkuk 1:6). Obadiah picks up the theme of the destruction, raging against the Edomites for despoiling Judah while the Babylonians destroyed the cities.

Haggai, Zechariah & Malachi

The last group within the Twelve Prophets is Haggai, Zechariah (especially chapters 1-8), and Malachi, all of whom prophesy after the Babylonian exile. (The history of this period, when the second Temple was being rebuilt,is described in the biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah.) Each of the three was preoccupied with a different issue. Haggai encouraged the people to rebuild the Temple, despite their grinding poverty. Zechariah (in chapters 1-8) focused on the theme of God choosing and desiring Israel: “Sing and rejoice, O daughter of Zion, behold I come and I will dwell within you, says the Lord” (Zechariah 2:14). Malachi spoke about the social and religious problems of the return to Zion: neglect of sacrifices (Malachi 1:6-14) and intermarriage (Malachi 2:11-12).

The historical setting of several passages in the Twelve Prophets are debated: Scholars argue about the dating of Habakkuk 3 and Zechariah 9-14, and it is quite probable that Zechariah 9-14 were written earlier than the time of Zechariah.

Joel

The dating of the entire book of Joel is also uncertain. Joel chapters 1-2 prophesy about a plague of locusts that would come upon the land, and urge the people to pray and repent. It is not clear if this refers to an actual plague or is a metaphor for an anticipated invasion of Judah.

Jonah

One of the Twelve Prophets stands out as unconnected to any historical event. This is the book of Jonah, also the only one to deal solely with universal themes, rather than with Israel’s particular relationship with God. In chapters 1-2, Jonah attempts to escape from God’s Presence; through his interactions with the sailors in chapter 1, he comes to see God as the source of life, and to long for God. In chapters 3-4, Jonah confronts God’s policy of reward and punishment, and is forced to undergo the experience of losing something he needs. Through this lesson, God teaches Jonah that His love for humans is overarching and that God is therefore inclined to be merciful and to prefer repentance to punishment.