The academic study of Judaism, including the modern, critical study of Jewish history, began in 19th century Germany. Early 19th-century German society afforded history a new and prominent role. The spirit of the age, romantic nationalism, argued that the forces of history and tradition were dominating factors in human behavior. Historian Howard Sachar explains, “To understand any belief or ideal, any custom or institution, one had merely to examine its gradual growth from primitive beginnings to its present form. The validity of any institution or idea was no longer to be measured by its reasonableness or utility, but rather by its origin and history.” In this manner, the 19th century became the age of historical investigation.

Modern historical investigation introduced the methodology of science to history. In an effort to discover “what really happened”–to separate fact from fiction–historians were expected to collect and analyze their sources objectively. The results, reasoned scholars, would dispel ignorance and promote understanding of people, cultures and institutions.

The birth of modern historical method coincided with a period of conservatism and mounting anti-semitism in Germany. During this period, maskilim (followers of the Jewish enlightenment movement) questioned why large segments of Christian society continued to display hostility toward them despite the fact that they had acquired knowledge of European culture and adopted its manners and behavior.

One group of maskilim reasoned that this continued hostility resulted from European society’s ignorance of Judaism’s history and its contribution to European culture. In order to present the treasures of Jewish creativity to the non-Jewish world, these Jews, mostly university students, founded a group dedicated to raising Jewish scholarship from obscurity to science, called the Society for Culture and Science among the Jews (Wissenschaft des Judenthums) in 1819.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

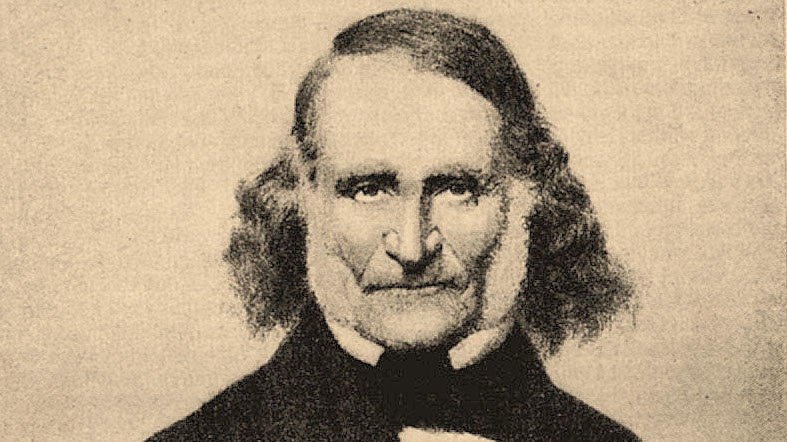

Leopold Zunz was a founder and leader of the Society. Zunz was a Jewish orphan who received a traditional religious education and taught himself secular subjects by reading German books. Begging and borrowing, he managed to attend the University of Berlin where he was exposed to German ideas of history and science. He ultimately received a doctorate at the University of Halle and thereafter made his living as a rabbi and Sunday School teacher for various Reform congregations. Zunz lead the Society in the attempt to master all the material incorporated into Jewish literature, to arrange it according to its historical development, and to relate it to world literature.

With such a huge task before them, it is not surprising that the Society ran out of energy in just a few years, but Zunz alone succeeded in realizing a major goal of the organization by cataloguing the lot of Jewish literature.

In his most famous work, Contributions to History and Literature, Zunz combed Jewish history to demonstrate that the Talmud, medieval poetry, homiletics, philosophy, and folklore all belonged to the realm of literature as they were authentic expressions of Jewish national life and thought. With the publication of this work in 1845, Zunz demonstrated that Jewish genius had not exhausted itself with the Bible as Christians had asserted. He revealed the wealth of the Jewish literary tradition.

Zunz attracted a group of followers, among them Mortiz Steinschneider, who devoted his life to Jewish scholarship. Steinschneider’s first book chronicled Jewish literature from the 8th to the 18th century. It was so well received that a year later he was called to Oxford to prepare a catalogue of Hebrew literature for the library there. Jewish scholarship had arrived!

In addition to Zunz and his group in Germany, other traditionally educated Jews who were interested in and familiar with Western European culture resolved to apply the new scholarly methods the classical sources of Judaism. Notable among these scholars were Samuel David Luzzatto, in Italy, and, in Galicia, Nahman Krohmal and Solomon Judah Rappaport.

The most famous Jewish historian to emerge during this period was Heinrich Graetz. His eleven volume History of the Jews would become the most widely read and consulted work in modern Jewish studies. It attracted much criticism, for although Graetz collected the facts in a scientific manner, his own ideas came through in his interpretation of the facts. His rare synthesis of scholarship and style popularized not only the history of the Jews but also the science of Judaism.

These first modern Jewish historians and the scholars who followed them faced issues both typical and unique in their efforts to record the Jewish past. Like all historians, Jewish historians must determine causality, create periodizaiton schemas (the division of history into identifiable periods), and take a stand on whether history is moving progressively toward a goal.

The job of the Jewish historian, however, is made more complex by the fact that their subject matter is, in the words of historian Michael Meyer “a protean entity–which seems to bear few if any constant characteristics and which for the far greater part of its history has been scattered without a land of its own.”

Jews have lived in all corners of the globe, and their daily life, including religion, has been influenced by the societies in which they lived. While Jews are influenced by larger societal trends, they are also affected by events that are unique to the Jewish experience. This “double consciousness”, a product of living as both part of and apart from larger society, results in complexity for historians of the Jewish experience, who must consider both the larger culture and Jewish culture when analyzing and understanding Jewish life.