Commentary on Parashat Vaetchanan, Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11

Reenacting an historical moment through liturgy and deed is a forte of Judaism. Our calendar year overflows with holidays and observances that transport us to our former days and inspire us to reenter the narrative and relive salient moments of history. This week in particular, observing the 9th of Av (Tisha B’Av), we read of the destruction of the Temple and continue the mourning of our ancestors for the calamities that befell them.

While it is possible to read this narrative as a preventive measure to ensure that we, too, do not fall victims to George Santayana’s dictum condemning us to either learn from our history or repeat it, I believe that Judaism’s message is a blessing, not a curse. It is a blessing for us to be able to relive life’s difficult moments–and the reason why can be gleaned from Moses‘ behavior and our portion this week.

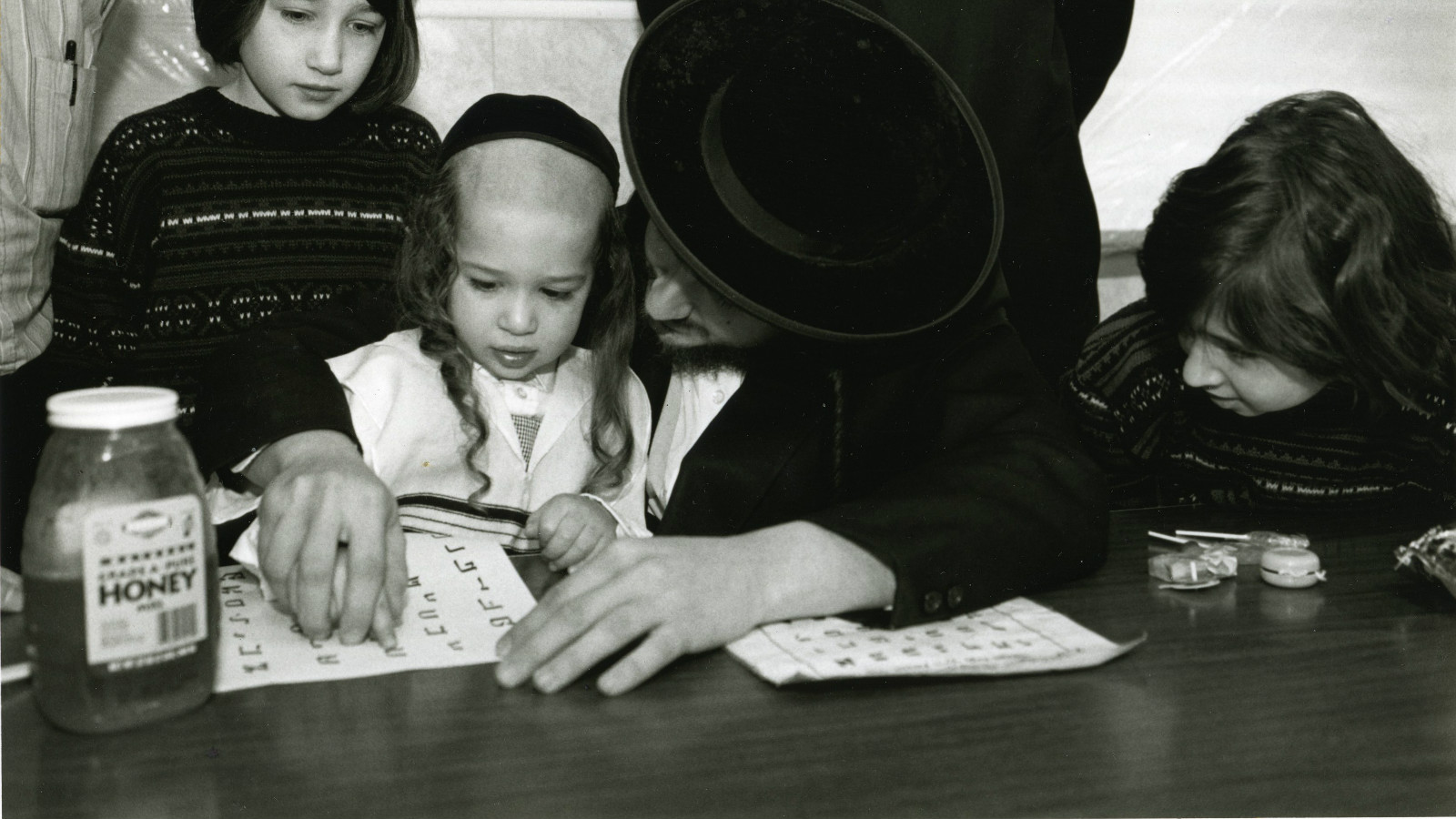

Isaiah Horowitz, commenting on this week’s Torah portion, Vaetchanan, asserts that throughout the portions of Devarim (Deuteronomy), we are constantly encouraged to learn and relearn the mitzvot (commandments) of the Torah. The common name of Deuteronomy itself, the Mishneh Torah, means a second retelling of what came before in the previous four books. Each subject of the Torah is rehashed within the pages of Deuteronomy, according to Horowitz, and each is a call to action to study the passages to our fullest comprehension. For inspiration, Horowitz patterns Moses as the quintessential student, constantly questioning the pedagogical message of God.

By citing and expanding on a from Yalkut Shemoni [a Bible commentary compiled in the 13th century], Horowitz enumerates the four times that Moses, as the student of God, did not fully comprehend God’s message and requested clarification of God’s objectives. The first of these occurs after Moses’ divine election as prophet for the people at the burning bush. He faithfully transmits God’s message to Pharaoh and the Midrash states that Moses is surprised by Pharaoh’s reaction. If God had meant to redeem the people, how could there be a negative response from Pharaoh? Should they not be redeemed immediately? Here, Moses questions the direction from God– seeking to understand fully what God’s underlying intentions are.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

The same questioning occurs when Miriam is stricken with leprosy and again when Moses is told to appoint Joshua as his successor. Each time, the result of his interaction with God is not as Moses expects, instead, the Midrash has him re-approaching God for clarification of his prophecy. Moses plays the dutiful student, seeking to understand a difficult lesson.

His final questioning of God occurs within this week’s portion. Moses beseeches God and recounts his request:

And I pleaded with the Lord at that time saying, O Lord God, you have begun to show your servant your greatness, and your mighty hand; for what God is there in heaven or in earth, that can do according to your works, and according to your might? I beg of you, let me go over, and see the good land that is beyond the Jordan, that goodly mountain region, and Lebanon. (Deuteronomy 3:23-25)

Questioning God’s ban prohibiting him from entering the land, Moses appeals to God to cancel the decree and allow him to enter. His plea to God is compared by Horowitz to asking that an oath be nullified. Moses focuses intently on canceling God’s oath preventing him from re-entering the land. In this, Moses is seeking to understand the ban, in its essence (Horowitz, Shnei Luhot ha’Brit, p. 107 Sharei Tzion ed.).

In his continual tendency to question and seek clarification and meaning, Moses provides us with a paradigm for a student’s responsibility. His goal is to relearn his prophecy until he fully understands its comprehensive message. In each situation, Horowitz explains that Moses is not challenging God’s message, but seeking to understand what he may have missed in the first telling.

As well it is with our calendar of holidays and observances. The historical message of each observance and holiday is clear, but our reasons for perpetuating them sometimes are not. Specifically, with Tisha B’Av, finding contemporary relevance in this day of mourning in an era in which the Jewish state has been re-established, can be particularly challenging. During the days of the Second Temple, as well, challenges were made to indefinitely postpone the fast of Tisha B’Av.

To guarantee relevance, we have defined this day on the calendar as the day on which numerous tragedies occurred. But our forte in Judaism is that of seeing relevance, not only through history, but also, as is evident in the example of Moses, through our own learning and relearning.

Each cycle of our calendar year is a call for us to refine and relearn our understanding of our holidays and observances. In Horowitz’s conclusion, he states that this pattern of relearning is what eventually leads to actualizing the verse, “You who held fast to the Lord your God are alive each and every one of you this day.” (Deuteronomy 4:4) Holding fast to our Judaism is not a passive observance but an active engagement — not simply passing through the calendar, but connecting to it and relearning our historic salient moments until we achieve the level of understanding inspired by Moses.

Reprinted with permission of the Jewish Theological Seminary.