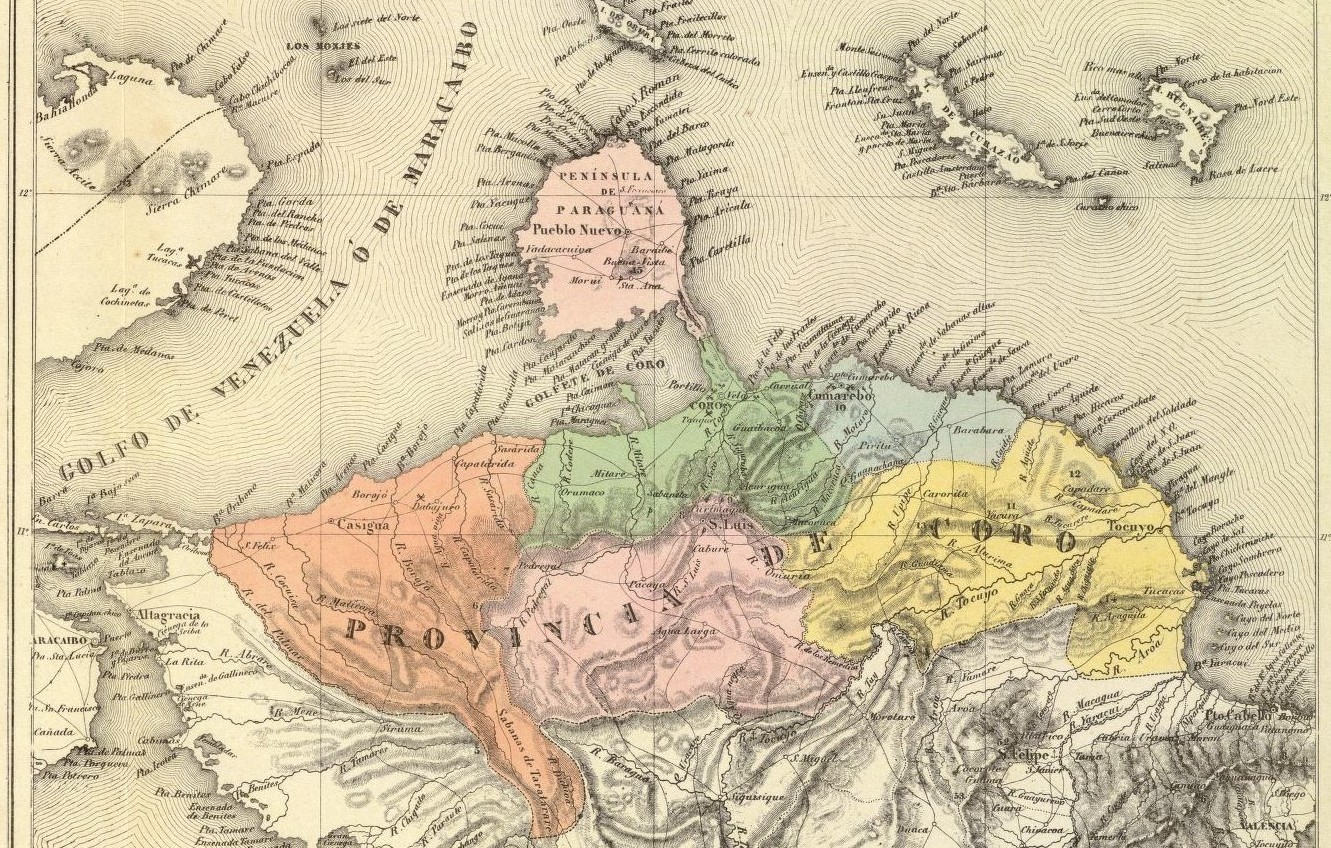

In 1827, a group of Jews emigrated from the tiny island of Curacao to the nearby mainland port city of Coro, Venezuela. Twenty-eight years later, violent rioting drove the entire Jewish population — 168 individuals — back to Curacao.

The hostility directed at Coro’s Jews was partly economic in nature. Venezuela’s banking system was in chaos, its government corrupt, and unemployment rampant. Xenophobia — resentment of foreigners — was running high.

Curacaoan Jews had immigrated to Coro at the urging of the colony’s Dutch government. In 1831, the Creole residents of Coro rioted to protest the rapid economic success that the immigrant Jewish shopkeepers and merchants had attained. While the local government suppressed the riots, in 1832 it imposed a special security bond which only Coro’s Jewish merchants had to pay.

The Jewish businessmen protested, so in 1835 the local government revised the tax so that all foreign entrepreneurs, not just Jews, had to pay twice as much for their business licenses as native-born Venezuelans. Despite this burden, and despite the hostility of the population, the Jewish merchants of Coro prospered. Historian Isidoro Aizenberg, writing in the journal of the American Jewish Historical Society, observed, “Their success could not have gone unnoticed, either by the population or the government.”

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Starting in the 1840s, the municipal government of Coro and the local military garrison asked the Jewish community for loans as advances against their taxes. These were made interest free, and at times were simply “voluntary” contributions as it became clear that the loans would not be repaid. Aizenberg notes, “With the passing of time these payments became not a financial resource which the government could tap in case of urgent need, but a regular source of funds which it came to expect as a matter of course.”

Fearing that the local military would grow powerful at the expense of civilian rule, the national government of Venezuela asked the Jews of Coro not to pay these unauthorized levies to fund salaries for the local garrison. The Jewish community acquiesced to the central government’s request and declined meet yet another request for funds. On January 30, 1855, unable to meet the payroll, the military command at Coro dismissed the troops quartered there.

The next day, a handbill circulated the city which asked, “Don’t we have businesses in this city that can help the Government by advancing funds for the garrison?” This question was followed by an extortionate threat: “Aren’t the businesses afraid to remain exposed to the dangers that such scandalous and unique circumstances may bring about?” A second and more direct handbill blamed the “distorted avarice” of the Jews for the “misery and helplessness” of the populace. It claimed that “many daughters of Coro, previously models of virtue,” were being “prostituted by the Jews.” It concluded by warning the Jews to leave Coro. Two nights later, a band of 30 armed men wandered through the streets, according to Aizenberg, “shooting at Jewish homes, tearing doors down and looting the shops” belonging to prominent Jewish merchants.

Like many at the time, Aizenberg believed that the military, wanting to intimidate the Jews into renewing their support, printed and distributed the leaflets, as well as supplied the manpower for the riots. Ironically, the strategy backfired. By February 10, the last of Coro’s Jews had fled the city on a ship sent by the government of Curacao to rescue its citizens. A pamphlet issued that day in Coro proclaimed, “With great joy in our hearts we see today our land is free of its oppressors . . . The Jews have been expelled by the people.” With them, of course, went the funds for any loans.

The Dutch governor of Curacao strongly protested their expulsion. The Dutch did not want to see the Jews expelled because their absence might harm Curacao’s trade with Coro, and they wanted to uphold the general principle that law-abiding foreign nationals had a right to protection under Venezuelan law and international treaties. The Dutch demanded that the Coro Jews be compensated for their losses and that their safe return to their adopted city be guaranteed. The Venezuelan government at first bridled at Dutch intervention and insisting that the Jews, if they considered themselves wronged, should sue in a Venezuelan court.

A stalemate lasted for three years. Two Venezuelan military officers confessed to writing the incendiary anti-Semitic pamphlets in 1855, but they invoked the right of free speech and were acquitted. Finally, when two years later, on May 6, 1858, the Venezuelans agreed to pay damages and guarantee the safe return of the exiled Coro Jews. On May 6, 1858, a pamphlet circulated in Coro proclaiming, “The people of Coro do not want Jews. Get out, get out like the dogs; and if you don’t leave soon the vultures will enjoy your corpses.” Some brave Jews did return, under a guarantee from a new military governor, but the number that returned was far smaller than the one that had departed three years earlier. Today, all that remains of the Jewish community of Coro are a few small commercial establishments owned by the descendants of the early Jewish settlers, and the old cemetery in which the settlers are buried.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.