The city of N. is built in three rings. First ring: the marketplace at the very center. Second: surrounding the market, the great city proper with its many houses, streets, byways, back streets where most of the popular lives. Third: suburbs.

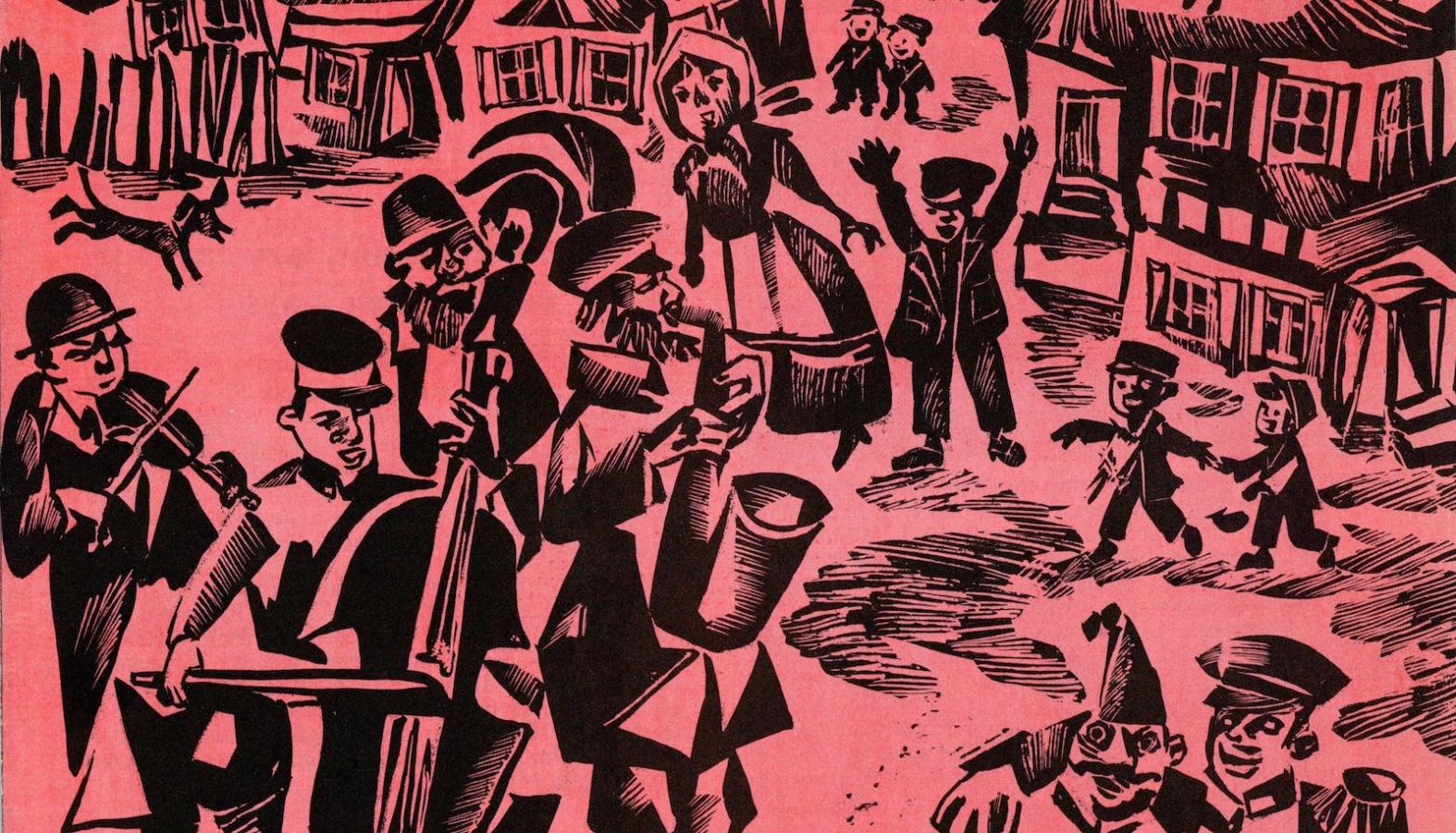

Should a stranger find himself in N. for the first time, he would at once be drawn, willy-nilly, to the city’s center. That’s where the hubbub is, the seething, the essential essence, the heart and pulse of the city.

His nose would be assailed immediately by smells: the smell of half-raw, rough or fine leather of all kinds; the acrid sweetness of baked goods; of groceries; of the salt smell of various dried fish; smells of kerosene, pitch, machine oil: of cooking and lubricating oils; of the smell of new paper. Of scruffy, shabby, dusty humid things: down-at-heels shoes; old clothes; worn-out brass rusted iron—and anything else that refuses to be useless; that is, determined, via this petty buying and selling to serve someone, somehow.

There in the marketplace are shop after shop, squeezed narrowly together like boxes on a shelf. If one doesn’t have a shop in the upper district, then he owns a warehouse in the lower. If he doesn’t own a warehouse, then he has at least a covered booth outside a shop. If no booth, then he spreads his goods out on the ground, or depending on what he sells, holds his wares in his hands.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

There, in the marketplace, it’s permanent fair. Wagons from nearby (or from distant) settlements arrive to pick up goods, and wagons from the railway depot endlessly discharge their loads —everything fresh, everything new.

Packing and unpacking!

Jewish tenant farmers, village merchants, come in from Andrushivkeh, Paradek, Yampole. They come from Zvill and Korets and even from the more distant Polesia. In summer, they wear their light coats and hoods. In winter, cloaks or fur coats with well-worn collars. They come to buy goods for cash or on credit. Some are decent and honorable—others are something else: their scheme is to buy on credit, then sell at a profit, then buy on credit again—then declare themselves bankrupt.

Wagons arrive empty and leave fully packed, covered with sacks, tarpaulins, rags—all of them tied down with cords. The wagons drive off at evening; others arrive at dawn.

“Sholom aleichem.” A storekeeper hurries down the steps of his shop to greet a newly arrived old customer, to lead him from the wagon directly into his shops lest some other merchant get at him. “Sholom aleichem, and how are things in Adrushivkeh?” he says with a show of familiarity, then eh gets right to business. “Ah, it’s good you’re here. I have just what you’re looking for. A marvelous this … a splendid that …”

Excerpt published in English by New York Review Books. Translation copyright © 1987 by Leonard Wolf.

Learn more about The Family Mashber and the struggle of Yiddish authors under Stalin.

Want to continue reading? Buy the book.