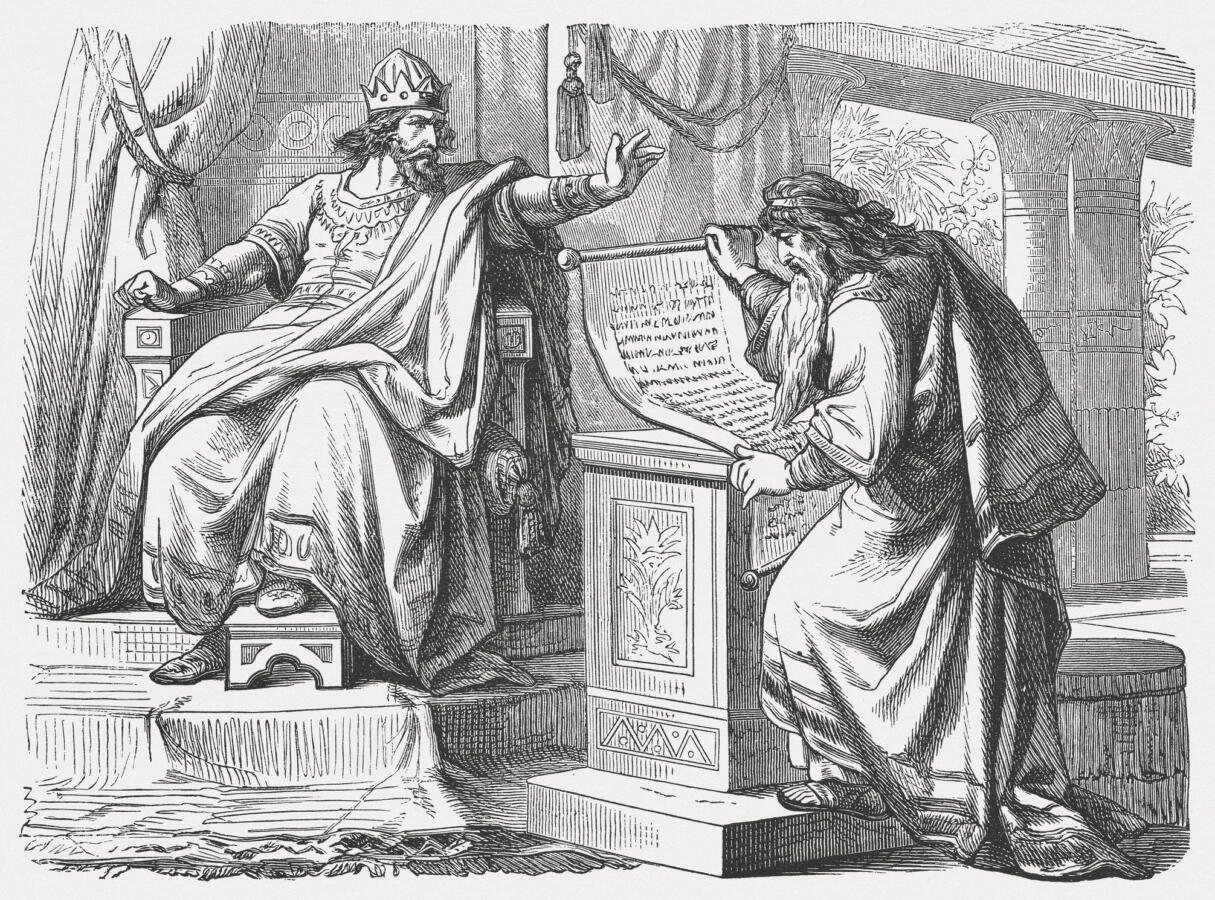

In the 18th year of King Josiah of Judah (622 B.C.E.), a remarkable discovery was made during temple renovations, according to 2 Kings 22:3-8. The high Priest Hilkiah came across a scroll that purported to be written by Moses himself–“the book of the law.” The king was greatly affected by what he read in his scroll, and it inspired him to begin a series of religious reforms that would last the rest of his reign and significantly change the face of the kingdom. The repercussions have lasted until today.

But what was this scroll? How long had it been sitting tucked away in the recesses of the temple? No one knows for certain the document’s provenance, but it has been positively identified as the law code now found in the book of Deuteronomy. (For convenience, scholars of the Torah refer to this Deuteronomic Code as D.)

D’s Concerns

The principal concern of the code is the covenant made at Horeb (Sinai) and its significance in Israel’s community. The scroll’s audience is reminded of the solemn pact made between Israel and its God and explains what that entails for Israel. For those who choose to live by the covenant, there will be life and blessings, and for those who do not, death and curses.

D’s Origins

It seems clear that the nucleus of the Deuteronomic Code goes back to a time centuries earlier than Josiah, as it preserves many ancient laws and customs from the days before the monarchy and reflects traditions of the priesthood and cult center at Shechem. However, there are other portions that are clearly late, such as the call for centralization of worship in a single sanctuary, a principle of exclusiveness that is unlikely to predate the time of Hezekiah.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

It is unclear whether these portions of the code were added by the Josianic editors or were already present in the code when it was found in 622 B.C.E. Since we are unable to identify the author or authors, we refer to the composer simply as the “Deuteronomist”. For the Judahites of Josiah’s day, the author was unquestionably Moses.

Josiah’s great reformation of Judah’s religious and national life is well-known and well-documented in the Bible (2 Kings. 22:3-23:25; 2 Chronicles 34:8-35:19). Included in this reform was the publication of a series of writings promoting the revival, no doubt royally-sanctioned texts, including the prophetic writings of Jeremiah and Zephaniah, who were loyal supporters of Josiah.

Epic Historical Narrative

However, the most significant of the new documents was a narrative history of Israel and Judah of epic proportions. This work, which runs from Deuteronomy to 2 Kings in present-day Bibles, used the Deuteronomic Code as its starting point and gauge, as it then proceeds to recount significant events in Israel’s history and to recall the kings of both kingdoms, judging them in the light of the code.

The author, whom we call the Deuteronomistic Historian (Dtr), reproduces the entire law code at the beginning of his work (with additions), but recasts it in narrative form as a sermon given by Moses on the plains of Moab. Placed in his mouth, these laws are given unparalleled authority. Moses is seen as the greatest of the prophets, the true prophet, who foresaw the destruction of the northern Kingdom of Israel for disobeying the covenant stipulations and the survival of Judah only in strict adherence to the covenant obligations.

Josiah the “Messiah”

The first edition of this history views Josiah as the fulfillment of the kingdom’s hopes. He was a “messiah” in the spirit of David, who could restore the empire to its former glory, politically and religiously, and lead its people in obedience to the Deuteronomic Code. The Deuteronomistic Historian apparently had access to official government documents, as well as older works of literature, some even of northern Israelite provenance, which he used to his advantage, incorporating these into the finished product; yet his hand is seen throughout the entire history.

The Fall of Judah

When Josiah was killed in battle unexpectedly, the high hopes of his supporters came crashing down. His successors on the throne were a disappointment to the Deuteronomic movement, to say the least. When Judah fell to the Babylonians in 586 and exiles were taken to Babylon, all seemed lost.

However, some in retrospect saw a lesson in what had happened to Judah, and it was decided that a new edition of the history would be valuable to a new audience. Seeing the fall of Judah as the result of failure to faithfully follow the Deuteronomic Code, the history was recast to demonstrate that the kingdom fell because of this negligence, in the same vein that the fall of Israel had been portrayed. The history was also extended to include the kings who followed Josiah and a description and explanation of the destruction of Jerusalem.

Editorial Activity

While it is possible that the composer of the original history was also responsible for the second edition, this is by no means certain, and therefore scholars use the designations Dtr1 and Dtr2 to refer to each of the authors, respectively (or the same author in two different capacities).

Sometime later, editors incorporated the history, along with other works, into the larger complex comprising Genesis through 2 Kings (“The Primary History”). The most likely period to place this editorial activity is in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah.

A Note on Terminology

This history is variously referred to by scholars as the “Deuteronomistic History” and the “Deuteronomic History,” with the former being the current favorite. It is the opinion of the present author that, while the adjective “Deuteronomistic” (“having the character of the Deuteronomist”) is an appropriate description of the author(s) of this history, it is not fitting for the history itself, since the comparison is not between the history and the author of the Deuteronomic Code, but between the history and the code itself. The designation “Deuteronomic History” therefore should be preferred (DH for short, in either case).

The Discovery of DH

Credit for the discovery of the Deuteronomic History goes to a German scholar, Martin Noth, who published his findings in his book, Überlieferungsgeschichtliche Studien in 1943. Noth noted that a similar language and ideology pervaded the books Deuteronomy through 2 Kings and demonstrated that a single individual was responsible for writing and compiling the entire history. His basic thesis is still held by almost all biblical scholars today, although there have been numerous refinements to his model.

One of these refinements is the theory that there were two editions of the history, one in the reign of Josiah, and one in the exile. This theory is associated with American scholar Frank Moore Cross and his students and has gained wide acceptance, especially in the United States.

Identifying the Author(s)

Several efforts have been made to identify the author or authors of the Deuteronomic History. Some have posited the existence of a Deuteronomic school, that is, a community of Deuteronomic traditionalists, who may be responsible for both editions of the history, as well as Deuteronomistic editing of other biblical books. Others have argued that a single person could have been responsible for all of the Deuteronomistic compositions in the Bible, since the work seems to have been done within a 60-year period.

While there is no way to establish for a certainty the identity of the person or persons responsible, a convincing case has been made by Richard Elliott Friedman that the Deuteronomistic Historian is none other than the scribe of the prophet Jeremiah, Baruch ben-Neriyah. This conclusion is based upon the fact that significant parts of the book of Jeremiah are written in the Deuteronomic style, some passages even duplicating word-for-word what we seen in the Deuteronomic History, and the book of Jeremiah points to Baruch as its writer (and therefore probably author of the narrative sections).