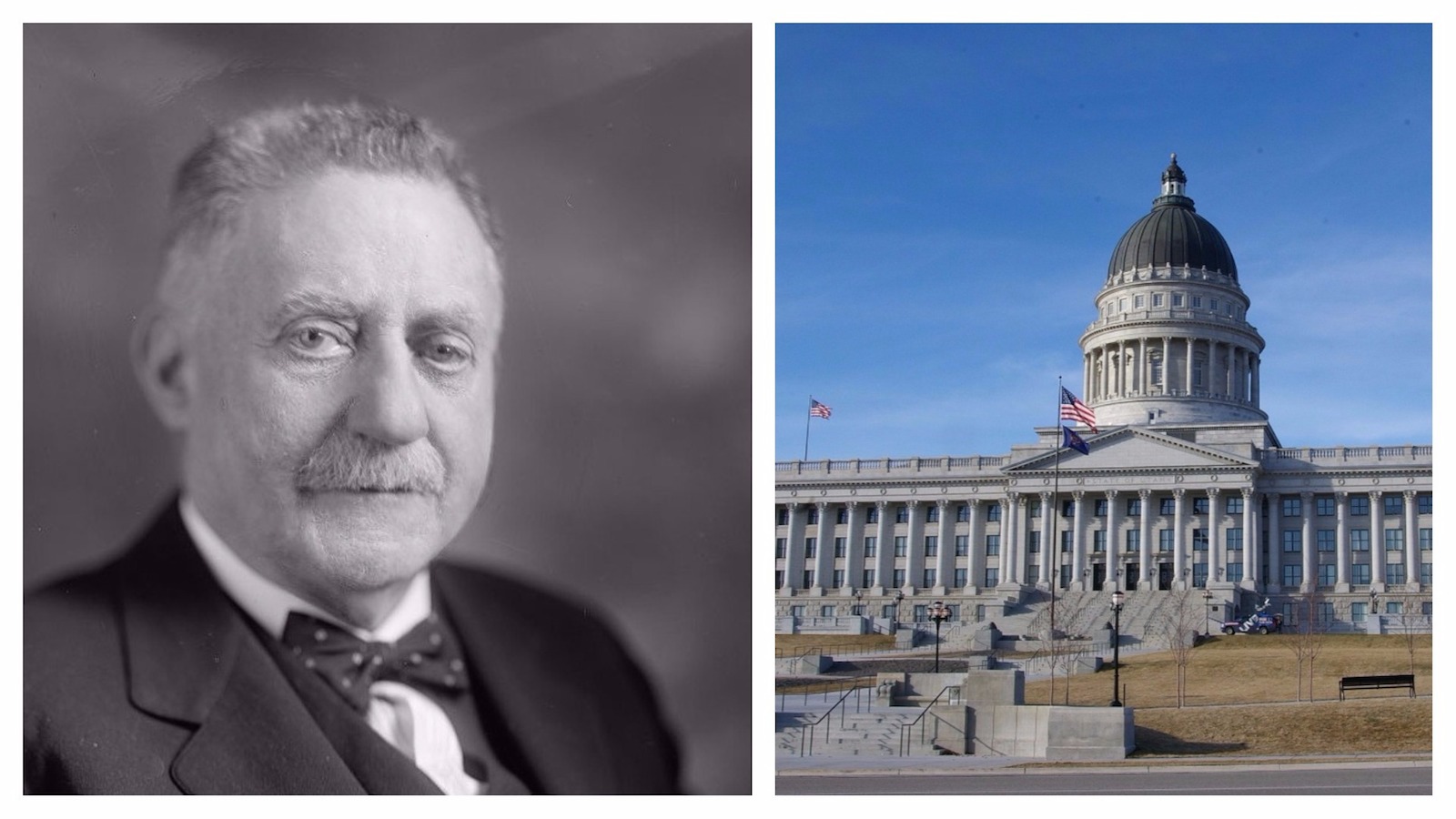

In 1916, Simon Bamberger ran for the office of governor of the state of Utah. Bamberger was the first non-Mormon, the first Democrat and the only Jew ever to seek that office.

During the campaign, Bamberger visited a remote community in Southern Utah that had been settled by immigrant Norwegian converts to Mormonism. According to historian Leon Watters, the community’s leader, a towering Norwegian, met Bamberger at the train and told him menacingly, “You might yust as vell go right back vere you come from. If you tink ve let any damn Yentile speak in our meeting house, yure mistaken.”

Bamberger is said to have replied, “As a Jew, I have been called many a bad name, but this is first time in my life I have been called a damned Gentile!”

The Norwegian threw his arm around Bamberger and proclaimed, “You a Yew, an Israelite. Hear him men, he’s not a Yentile, he’s a Yew, an Israelite. Velcome my friend; velcome, our next governor.” The Norwegian was correct; Bamberger won the election.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

From the founding of their religion in 1830, Mormons (or Latter-Day Saints, as they are named) have respected Judaism as a religion. Joseph Smith, founder of Mormonism, proclaimed that “Lehi, a prophet of the tribe of Manasseh . . . led his tribe out of Jerusalem in the year 600 BC to the coast of America.” The 10th “Article of Faith” of Mormonism proclaims, “We believe in the literal gathering of Israel and in the restoration of the Ten Tribes; that Zion will be built upon this (the American) continent.” In Mormon metaphor, the Utah desert was a latter-day Zion, and the Great Salt Lake a latter-day Dead Sea. The Mormons who settled there under Brigham Young’s leadership were, in their own minds, direct descendants of the ancient Hebrews. Accordingly, the early Mormons referred to all non-Mormons —regardless of their religion — as “Gentiles.” Watters observes, “Utah is the only place in the world where Jews are Gentiles.”

The pioneer Jews of Utah fared well under the Mormon majority. Because Mormon doctrine proclaimed agrarian pursuits the only respectable calling and commerce morally corrupting, the role of shopkeeper, banker, and businessman were left to Utah’s Jews and other Gentiles. In early Utah, Jews and Mormons lived in symbiotic, commercial harmony.

Born in Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany, in 1846, he emigrated to America at age 14 in search of his fortune. After spending a few days in New York, the young Bamberger departed by train for Cincinnati. He fell asleep and missed his transfer at Columbus, Ohio. Instead, he disembarked in Indianapolis, where he had a cousin. After working in Indianapolis until the Civil War ended, Simon and his bother Herman, who migrated to the United States after Simon, moved to St. Louis and became clothing manufacturers. On a trip to Wyoming to collect a debt, Simon learned that the business had failed. He decided to travel on to Utah as, in his own words, he “had no other objective in view” and few prospects back in St. Louis.

The enterprising Bamberger purchased a half interest in a small hotel in Ogden, Utah. In Bamberger’s own words, “Soon thereafter an epidemic of smallpox broke out and the Union Pacific passengers were not permitted to come up to the town, so I gave up. I took the Utah Central to Salt Lake and there bought the ‘Delmonico Hotel’ . . . and renamed it the ‘White House’ in partnership with B. Cohen, of Ogden.” The hotel flourished.

In 1872, Bamberger purchased an interest in a silver mine which, by 1874, made him wealthy enough to retire. However, the pioneering spirit was too strong in Bamberger to allow him to rest. Two years later, he raised a million dollars to construct a railroad to some coal mines in northern Utah in which he had invested. Bamberger then built a second rail line to some small towns on the outskirts of Salt Lake City. Railroad competition was fierce, however, and Bamberger lost much of his fortune in the effort.

In 1910, Bamberger helped establish a Jewish agricultural colony in Clarion, Utah, and remained one of its most ardent supporters. In 1913 and again in 1915, when the immigrant Jewish farmers became bankrupt, Bamberger traveled east to raise funds to pay off their debts. His efforts could not save the colony, however, and it folded in 1915.

His Mormon friends noted Bamberger’s civic mindedness and urged him to run for governor. Despite being a Democrat, Bamberger’s policies paralleled those of Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressives. He insisted that the legislature balance the state budget, create a public utilities commission to regulate the price of electricity and gas, and ban gifts from utility companies to public officials. He passed a modified line-item budget veto; created a state department of public health; instituted water conservation; and advocated for a lengthened school year, workers’ compensation, the rights of unions, and the non-partisan election of judges. Bamberger, a teetotaler, supported prohibition. He saw most of his platform voted into law.

Bamberger died in 1926 and is buried in the cemetery of Congregation B’nai Israel, the first synagogue in Salt Lake City. Of course, he’s buried in the “Yentile” section.

Chapters in American Jewish History are provided by the American Jewish Historical Society, collecting, preserving, fostering scholarship and providing access to the continuity of Jewish life in America for more than 350 years (and counting). Visit www.ajhs.org.