The Jewish presence on the Italian peninsula dates back to ancient Roman times. The Jews of Italy’s capital city claim to be the oldest continuous Jewish community in Europe.

Italy only became a unified country in the latter part of the 19th century, before which it was a patchwork of regions invaded, occupied and ruled at different times by different powers. The history of Italy’s Jews reflects this, alternating between periods of prosperity and persecution depending on the ruler.

“No other place in the western Diaspora can indeed boast a Jewish presence that has been so ancient, widespread and constant,” the scholars Anna Foa and Giancarlo Lacerenza wrote in their book on the first 1,000 years of Jewish history in Italy.

Italian Jews in Antiquity

Jews probably lived in Rome by the third century BCE. In 161 BCE, only a few years after defeating the Seleucid King Antiochus, Judah Maccabee sent a diplomatic mission from Judea to Rome headed by Jason ben Eleazar and Eupolemos ben Johanan. According to the historian Cecil Roth, the fact that the names of the two Jewish ambassadors are known bears a special significance.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

“These are the first Jews to be in Italy, or to visit Europe, who are known to us by name,” Roth wrote in The History of the Jews in Italy. They are “the spiritual ancestors of Western Jewry as a whole.”

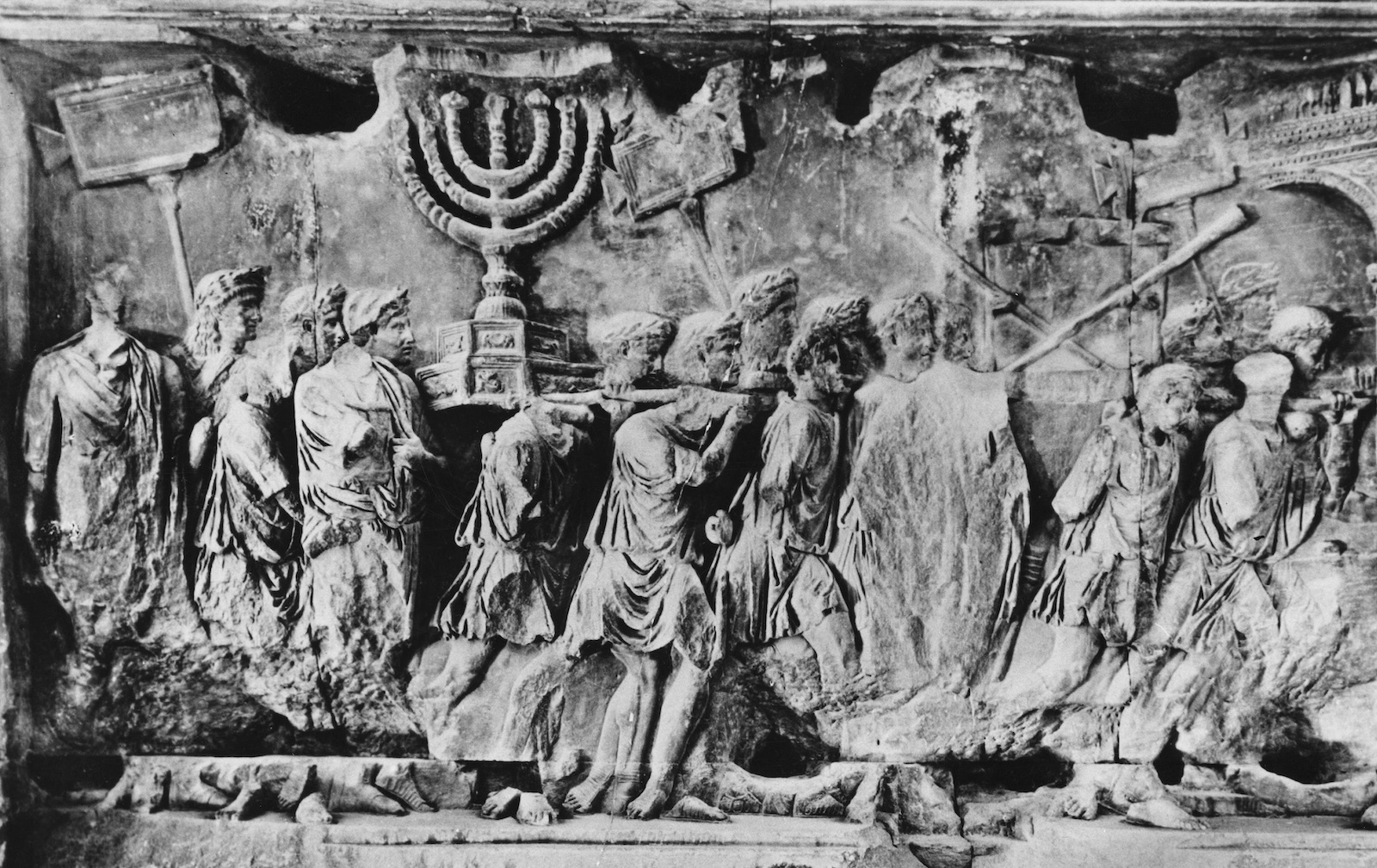

Ancient Rome’s Jewish population was swollen by slaves and prisoners brought back after the sack of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE. The Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum bears a famous carving showing Roman forces in a triumphal procession bearing the menorah and other loot from the destroyed Temple. The arch was such a powerful symbol that Roman Jews refused to walk through it for centuries. They finally did so only in 1948, joyously parading beneath it to celebrate the birth of Israel.

From late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, most Jews lived in well-established communities in southern Italy and Sicily. Jewish catacombs and other archaeological evidence demonstrate a sizable Jewish population at Venosa, an important ancient crossroads between Naples and Bari from the fourth to the ninth century.

The 12th-century Spanish Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Italy on his journeys in the 1160s and 1170s. His trips took him to several Jewish communities in southern Italy, but he mentioned only two major Jewish communities north of Rome: Pisa and Lucca.

Middle Ages and the Renaissance

Jewish communities flourished in central and northern Italy in later centuries, bolstered by Sephardic Jews fleeing Iberia after the expulsions in the late 15th century and by small groups of Ashkenazi Jews from central Europe. Great ports such as Venice, Ancona and Livorno became crossroads of Jews from many lands and backgrounds. In some cities, Jews of different traditions built separate synagogues.

But in the decades after the expulsion of Jews from Iberia, Spanish rulers also banished all Jews from Sicily and south of Rome. Jews consequently moved north, to Venice, Ancona, Florence, Bologna and Padova. Both secular and religious authorities began instituting further restrictive measures. In 1516, civic rulers in Venice forced Jews to live in a closed district on the site of an old foundry. The word “ghetto” is believed to come from “geto,” the Venetian dialect for foundry.

In 1555, Pope Paul IV instituted the ghetto in Rome and other cities in the papal states. Branding the Jews killers of Christ, the decree condemned Jews to live in segregated areas, barred them from owning property or having more than one synagogue per community, forced them to trade only in secondhand clothing and required them to wear a distinguishing yellow hat or other mark. In 1569, Pope Pius V went further. He expelled Jews from almost everywhere in the papal lands, allowing them to live only in the ghettos in Rome and Ancona. Many Jews fled northward. Within little more than a century, closed Jewish ghettos were in place in most towns and cities in Italy that were home to Jews. New ghettos continued to be established until the end of the 18th century.

Despite this, Jewish religious and cultural life flourished during the ghetto period. Venice became a major European center of Hebrew publishing, for example, and behind anonymous outer walls, highly decorated synagogue sanctuaries were built.

Emancipation and the Holocaust

The emancipation of the Jews and the abolition of the ghettos didn’t take place until the 19th century. Napoleonic rule in north-central Italy eased restrictions on Jews for a brief period at the turn of the century, but this was followed by a renewed crackdown after Napoleon’s fall in 1815. With the Italian peninsula still under a variety of regional rulers, Jews became involved in the general struggle for unification, taking an active part in the Risorgimento, or Italian liberation movement, between 1848 and 1870.

The defeat of papal forces and confinement of the pope to Vatican City in 1870 brought down the gates of the last closed ghetto, in Rome. With emancipation, Italian Jews eagerly adopted an Italian identity and quickly integrated into mainstream society.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they built grand new cathedral-style synagogues that proclaimed their pride and freedom and they entered all professions and walks of life. There were already Jews in parliament in 1871; Italy had a Jewish prime minister, Luigi Luzzatti, in 1910; and between 1907 and 1913, Rome had a Jewish mayor, Ernesto Nathan.

Like Italians in general, Jews backed both liberal and conservative political movements. Thousands of Jews even joined Benito Mussolini’s Fascist party. In 1943, after Allied troops moved through southern Italy, Nazi Germany occupied northern Italy and began deporting Jews to their deaths. More than 8,000 Jews, around a quarter of the Jewish population, were deported and killed.

Italy’s Jews today

Today, Italy’s affiliated Jews number fewer than 30,000 out of a total population of 60 million. Around three quarters live in Rome and Milan with the rest in a handful of other towns and cities, almost all in northern Italy. But despite their small numbers, they make up a multifaceted, complex community, whose richness and diversity — combining Ashkenazic, Sephardic, native Italian and other Jewish traditions — bear witness to a complicated history dating back to antiquity.

Many Jews in Italy today are immigrants (or the children of immigrants) who came to Italy in the past few decades, including thousands of Libyan Jews who fled after bloody anti-Jewish riots in 1967. Three main types of religious rites are celebrated: Sephardic, Ashkenazic and Italian — the latter a local rite that evolved from the Jewish community that lived in Italy before the destruction of the Temple.

The vast majority of Italy’s Jews are nominally Orthodox. Most, however, are not strictly observant. Even observant Jews are typically highly acculturated, with a strong Italian as well as Jewish identity. Jews are active in all fields, from the arts to business to politics, and despite their small numbers hold prominent positions.

All officially established Italian Jewish communities are Orthodox and operate under the umbrella of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI), which is their official collective representative to the state. Particularly in the larger communities, there is a well-organized infrastructure of schools, clubs, associations and other services, including a rabbinical college.

Reform and Conservative Jewish streams are not officially recognized by the UCEI, although several small liberal Jewish communities have developed in Rome, Milan and Florence. They function outside of UCEI but affiliate with international progressive Jewish organizations. Chabad also operates outside the UCEI umbrella, with an active presence in Rome, Milan, Venice and Bologna.

In 1986, Pope John Paul II visited Rome’s towering Great Synagogue, the first ever visit by a pope to a Jewish house of worship. John Paul made bettering relations between Catholics and Jews a cornerstone of his papacy, and his visit to the synagogue marked a watershed moment in the process — and was particularly significant for the Jews of Rome, who had suffered for centuries under oppressive papal rulers. His successors, Popes Benedict and Francis, also visited the synagogue and reaffirmed their commitment to Jewish-Catholic dialogue.