“The State of Israel will be open to the immigration of Jews and the ingathering of exiles from all countries of their dispersion,” asserts Israel’s Declaration of Independence. The 1950 Law of Return codified this mission to gather Jews from around the world by granting them the right to settle in Israel and gain automatic citizenship.

Jews & Arabs

One of the major goals of the Law of Return is to ensure a Jewish majority in Israel. Today, over 20% of Israeli citizens are Arab, and this number could continue to rise. The Law of Return offsets the high Arab birth rate by enabling the naturalization of thousands of Jewish immigrants to Israel each year.

However, critics argue that because the Law of Return favors Jews it is undemocratic and, according to a more extreme position, racist, and must be replaced with a more egalitarian immigration policy.

Many pro-Palestinian advocates criticize the Law of Return as discriminatory, because Israel does not grant a similar right of return to Palestinian refugees who wish to return to their former homes in Israel, after being displaced in the 1948 War of Independence and the 1967 Six-Day War. Today, the number of Palestinian refugees and their descendants is estimated to exceed four million. Many Israelis worry that granting the Palestinian right of return would lead to an Arab majority in Israel and the eventual dissolution of the Jewish state. The right of return has been a contentious topic of negotiation in the Israeli-Arab peace talks.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Who Is a Jew?

There are also disputes concerning who exactly is included in the Law of Return, since the 1950 law did not define who is a Jew for the purposes of immigration.

The first major challenge to the law came in 1962 with the Brother Daniel case. Brother Daniel, born Oswald Rufeisen, was a Polish Jew who converted to Catholicism during the Holocaust. He later became a Carmelite monk, and in this position saved many Jews during the Holocaust. When Brother Daniel applied to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that he was ineligible because the Law of Return does not include Jews who practice another religion.

Then in 1969, the Israeli Supreme Court in the Shalit case ruled that a child born in Israel to a Jewish Israeli father and non-Jewish mother could be registered as Jewish in Israel’s Population Registry. Since this ruling runs counter to the traditional Jewish legal definition of a Jew–someone born to a Jewish mother–tremendous controversy ensued, which led to the 1970 amendment of the Law of Return.

This amendment expanded the right of return to include the child or grandchild of a Jew, and the spouse of a child or grandchild of a Jew. For the purposes of this law, “Jew” was defined as someone who has a Jewish mother or who converted to Judaism, and is not a member of another religion.

By including the children and grandchildren of Jews, the 1970 amendment is reminiscent of the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws. Any person who would have been targeted by the Nazis for being Jewish, the amended law implies, deserves the right to safe haven in Israel.

Non-Orthodox Conversion

The question of whether non-Orthodox converts should be included in the Law of Return has also been debated for decades. Since the 1970 amendment, the ultra-Orthodox parties in Knesset have advocated limiting the Law of Return to Orthodox converts.

In 1988, Yitzhak Shamir tried to convince the ultra-Orthodox parties to join his coalition by offering them the prospect of amending the Law of Return to include only those converts who converted to Judaism “according to Jewish law.” But leaders of Jewish Federations in America understood this to de-legitimate the non-Orthodox branches of Judaism. They threatened that American Jewish support of Israel cannot be taken for granted, and Shamir withdrew his offer.

Then in 1989, the Supreme Court ruled that anyone who converted to Judaism in a non-Orthodox conversion outside the State of Israel is included in the Law of Return. Orthodox leaders, particularly the Israeli rabbinate, were outraged at the Supreme Court’s ruling. But the ruling was only a partial success for liberal Judaism, because it still did not include those who converted in non-Orthodox ceremonies in Israel. Because of this technicality, many non-Jews living in Israel who want to convert through non-Orthodox rabbis are forced to become “leaping converts” who study for conversion in Israel, convert with non-Orthodox rabbis abroad, and then return to Israel.

In addition, the Israeli Rabbinate, which has a monopoly on marriage and divorce between Jews in the state, does not accept non-Orthodox converts as Jewish. As a result, non-Orthodox converts admitted to Israel under the Law of Return cannot marry or divorce in the country. In recent years, the Israeli Rabbinate has even questioned the legitimacy of many Orthodox conversions performed abroad.

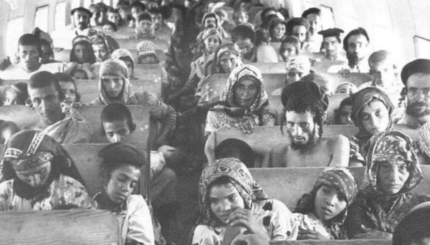

Immigrants from Ethiopia and the Former Soviet Union

In the last two decades, some important questions regarding the Law of Return have come to the fore as large groups of immigrants have arrived in Israel from Ethiopia and the former Soviet Union.

The Falash Mura, who claim to be descendants of Ethiopian Jews who converted to Christianity several generations ago, have been seeking to immigrate to Israel for two decades. Israel has already admitted thousands of Falash Mura, both under the Law of Return and, if they do not qualify for admission under the Law of Return, for humanitarian reasons. Yet thousands more live in camps in Addis and Gondar, and their eligibility for Aliyah has not been determined by Israel’s government.

Over a million people from the Former Soviet Union have immigrated to Israel since 1989. Though these immigrants have Jewish ancestry, many are not Jewish according to Orthodox (and in many cases even liberal) interpretations of Jewish law, and some do not identify as Jews. Some Israelis, concerned that these immigrants threaten the Jewish character of the state, argue that Israel should limit immigration from the FSU. Others argue that Israel needs to make conversion more accessible, and work to ease the integration of immigrants from the FSU into Israeli society.

In the wake of these controversies, Israelis debate possible reforms to the Law of Return, and what it means for Israel to be a homeland for Jews all over the world–not only a place to which Jews can freely immigrate, but also a country that can successfully integrate the diverse Jews that seek a home there.

Knesset

Pronounced: k'NESS-et, Origin: Hebrew, Israel's parliament, comprising 120 seats.

Yitzhak

Pronounced: eetz-KHAHK, Origin: Hebrew, Hebrew name for Isaac.