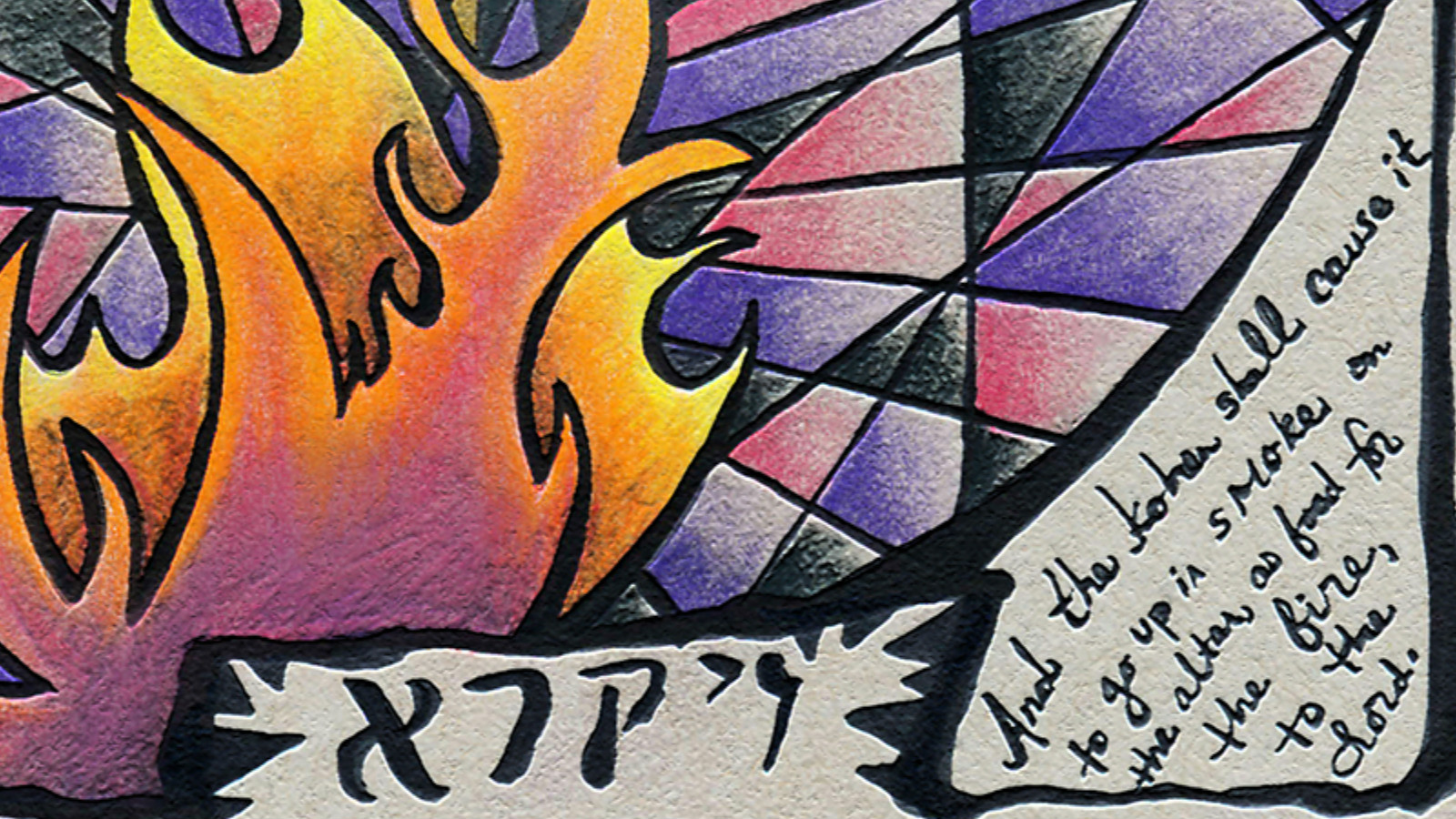

Commentary on Parashat Vayikra, Leviticus 1:1-5:26

This week’s Torah portion opens the third book of the Torah, with which it shares a name: Vayikra. In a sefer Torah, a hand-written scroll used for ritual Torah readings, the letter aleph at the end of the word vayikra is noticeably smaller than the other letters.

There are practical explanations for this anomalous little aleph. For example, Rabbi Shmuel David Luzzato (the Shadal), a 19th-century Italian scholar, wrote that the small aleph is a useful way for scribes to distinguish the aleph at the end of vayikra from the next word, el, which begins with an aleph. The small aleph at the end of vayikra ensures that neither adjacent aleph is accidentally deleted in the process of writing. But a difficulty for this interpretation is that most of the time when two side-by-side words end and start with the same letter we write those letters identically.

Other interpreters take a less prosaic view of the small aleph. Perhaps the most prominent midrashic explanation is that the size of the letter was due to a decision made by Moses while writing the Torah. According to this midrash (Kitzur Ba’al HaTurim, Leviticus 1:1), Moses’ humility would not allow him to write the words God dictated, vayikra el Moshe — “and [God] called to Moses” — because the idea that God called directly to Moses made it sound as if he were someone special. Instead, out of humility, Moses asked God to write the word without an aleph, as vayikar. This would have changed the meaning to “and [God] happened” — suggesting God began speaking to Moses by chance. According to the midrash, God declined the change and insisted that Moses write the aleph at the end of the word. Moses complied, but wrote the aleph smaller than the other letters.

Centuries later, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the LubavitcherRebbe, connected this midrash about the small aleph of vayikra with another (less commented-upon) moment in the Hebrew Bible in which an aleph is enlarged. First Chronicles, which opens with a family tree of humanity, starts with the name Adam — which also begins with an aleph. The aleph at the beginning of Adam’s name in this verse is written larger than the other letters. Rabbi Schneerson sees this large aleph as a sign of arrogance characterizing Adam and his approach to the world; as the first man responsible for ruling over the other creatures, and the climax of God’s creation of the world, Adam ultimately became too prideful, which led to his downfall and expulsion from the Garden of Eden. In his view, the small aleph in vayikra was Moses’ way of compensating for the arrogance of the first man.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Taken together, these midrashic understandings are fascinating, both for what they say about storied biblical characters and perhaps even more so for how they envision the process of writing the Torah. We normally think of Torah as something God dictated to Moses, whose passive role was simply to write it down. But in this midrash, Moses aspires to the role of editor or perhaps even coauthor, seeing the words God gives him to write as mutable, something he can negotiate and adjust. Though God declines Moses’ editorial input, by rendering the aleph smaller than the other letters, Moses takes a level of control not only over the writing process, but his place in the biblical narrative — and perhaps provides some restitution for the faults and imperfections of another character in the grand story. Moses may not get his way about changing one of God’s words, but with the small aleph he leaves us with a legacy both of his personal modesty and textual empowerment — a sense that we are able to be part of the text of tradition and write our own meaning into it.