Commentary on Parashat Masei, Numbers 33:1 - 36:13

From war to terrorism to gun violence, the tragic deaths we see almost daily in the news sadly serve as background for this week’s portion, Matot-Masei. They also serve as a contemporary introduction to the traditional Nine Days of mourning, which start with the beginning of the month of Av. During the month of Av, Jerusalem was burned to the core in 70 CE, and half a century later the Romans created a bloodbath in the city of Beitar, the last stronghold of the rebellious Judean army led by Bar Kochba.

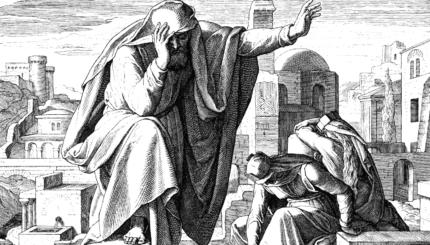

Our double portion this week, Matot-Masei, also talks about war and killing, but, rather than the Romans killing, it is Moses ordering the Israelites to kill, and, painfully, to kill more. In some of the most disturbing verses in the Torah, Moses gets angry with the Israelites for not killing enough of the Midianites, who tried to destroy the Israelites by ensnaring them in idolatry. He shouts: “You have allowed all the women to live! … So now I want you to kill every male child (the male adults were killed already) and every woman…” (Deuteronomy 31:15-17) This is our beloved Moses speaking! Rabbi David Hartman, the founder of Jerusalem’s Shalom Hartman Institute. used to cringe when he heard these verses read in synagogue, but he recognized that they are an integral part of the Torah and cannot just be cut out. We have to address them. In fact, I believe God, too, wants us to cringe at verses like these. We are meant to be shocked; we are meant to say, “Moses, is this really what God commanded?”

More than 3,000 years after Moses, Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (of Lithuania) could not accept the Talmud’s literal meaning of the verses, and at least, in his interpretation, many innocent women are excluded from the killing. Yet we need look no further than the Torah, to see that Moses himself is outraged by his own command, a command that presumably came from God. Moses’s discomfort with the whole enterprise of killing might explain why he is so angry having to tell people that they have not killed enough. Then, immediately after his bloody order, he declares:

You [who have killed the enemy] must stay outside of the camp for seven days; anyone who has killed a human being (even the enemy!) or even has touched a corpse, must remove sin from themselves on the third and seventh day…” (Deuteronomy 31:19)

This is the same Moses who just ordered these terrible killings. On the one hand, to protect the Israelites, to enable them to survive in a kill-or-be-killed environment, people will be killed. Moses is the first to recognize that, as frustrating as it is. Yet, Moses also realizes the toll that that killing takes on the killer: Justified or not, taking a life is a traumatic act that must be recognized, mourned and accentuated. No one can continue business as usual after experiencing a death, let alone perpetuating one.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Where does this leave us peaceful and gentle people, who hopefully will never experience the killing of a human being? Our tradition strives to teach us how valuable life is by using Moses’ message of the trauma of taking a life when we take the life of an animal to fill our stomachs. The rabbis wanted us to take a certain amount of time after eating meat or poultry— anywhere from an hour to six hours — before we are allowed to enter the “camp” and raid the freezer for ice cream or the fridge for milk or other dairy products. This brief period of tum’ah — spiritual trauma — reflects the trauma that should come from taking any life, the life of a bird or animal, let alone a human life. We are allowed to take animal life to eat, but even if we do so, we are still taking a form of life. Think twice before eating from an animal or bird that has been killed: It does something to the human soul — even though I love steak! — and when we realize that taking any life is significant, then, God-willing, taking human life will be almost unthinkable.

There is a custom not to eat meat or poultry as we enter the Nine Days of mourning. Perhaps one extra reason for this prohibition is to sensitize us to what it means to take a life — even the life of an animal, which our tradition allows us. Let us hope that avoiding taking even animal life can re-sensitize us to the loss of human life that tragically still occurs around us as it did in the days of the Romans and of Moses. As Moses knew, all life is precious.