The tabernacle (mishkan), first mentioned in the in Exodus 25, was the portable sanctuary that the Israelites carried with them in the wilderness. Mishkan comes from the Hebrew root meaning “to dwell”; the tabernacle was considered to be the earthly dwelling place of God. In Exodus 25:8-9, God instructs Moses to tell the Israelites to build a mikdash (sanctuary) where God may dwell, specifying exactly how the tabernacle should be designed.

What the Tabernacle Looked Like

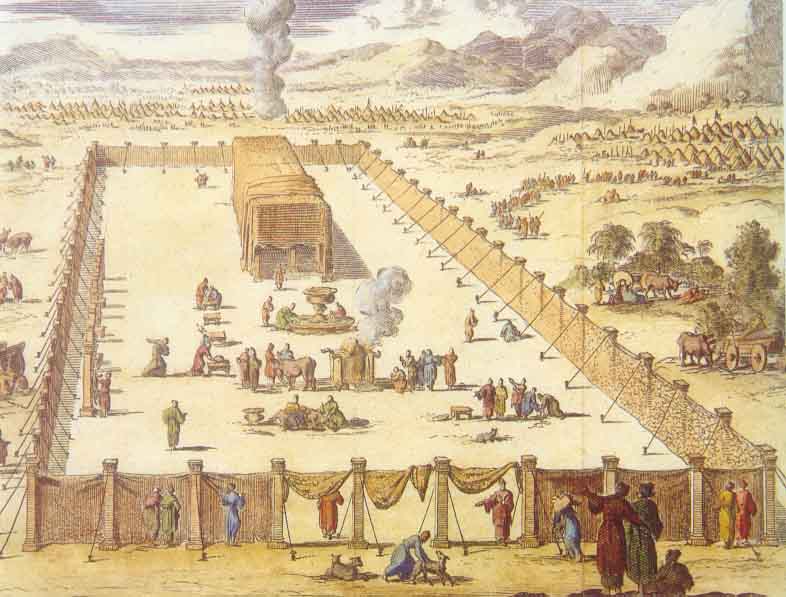

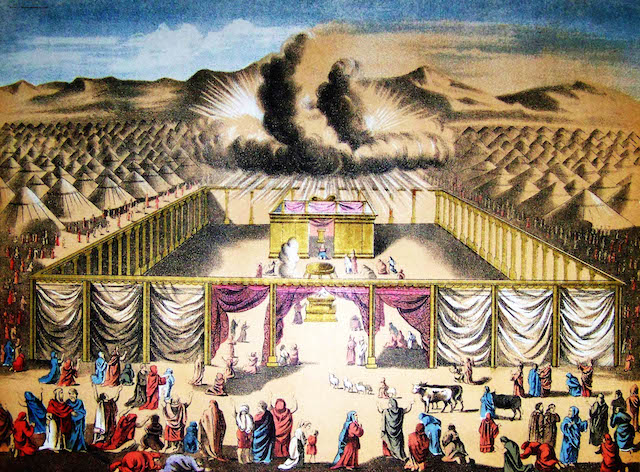

The Book of Exodus goes into elaborate detail to describe the design and construction of the tabernacle. The tabernacle was surrounded by a rectangular fence with a gate, which enclosed an outer courtyard area. An altar for burnt offerings (sacrifices) stood in the courtyard. Deeper into the courtyard, a screen sectioned off the “Holy Place” from the rest of the area. Even deeper, a curtain created a barrier to the “most holy place,” the Holy of Holies.

This innermost and most holy area of the tabernacle was designated to house the of the covenant, the place where the tablets of the law would be stored. The ark was to be made of acacia wood and overlaid with pure gold. The Torah provides precise measurements for building the ark: “two and a half cubits long, a cubit and a half wide, and a cubit and a half high” (Exodus 25:10). Acacia poles overlaid with gold were used for carrying the ark through the desert. A cover for the ark was required, with decorations of two gold cherubim (angels), one on each side, facing each other with outspread wings. Additional instructions include the production of ritual items: a table, “bowls, ladles, jars, and jugs,” and an intricately designed six-branched menorah, or candelabra (Exodus 25:29-38).

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Exodus 26 details the construction of the tabernacle, which was a tent-like structure covered with 10 strips of linen cloth. The cloth was to be made of blue, purple, and crimson yarn, with the cherubim motif from the ark cover recurring here. The text goes on to detail the exact number of loops and gold clasps by which each cloth should be tied to the next. It adds that 11 cloths of goat hair should cover the tabernacle, connected by loops and copper clasps. Further, ram skins and dolphin skins were to be used as further covering for the tabernacle.

The Tabernacle’s Significance

The tabernacle was considered to be the place where God’s presence dwelled among the Israelites, where the divine and earthly realms met. The tabernacle’s design physically represented a gradual increase in gradations of holiness, from the outer courtyard (meant to create a barrier from the profane realm) to the Holy of Holies (only entered once a year on by the High Priest).

Various commentaries interpreted the significance of the tabernacle in different ways. Maimonides saw the tabernacle as an image of a royal palace.The Zohar, a mystical text believed to have been written in the 13th century, saw the tabernacle as a reflection of the process of the creation of the universe. Indeed, the points out, the language used to describe how God created the universe in the Book of Genesis is identical to the language used to describe the artist Bezalel’s building of the tabernacle in the Book of Exodus.

The 19th-century Russian-Jewish commentator known as the Malbim provided a symbolic explanation for the relevance of the tabernacle. It was not that God needed a physical sanctuary on earth, but that each one of us is called to build a tabernacle for God in our hearts, preparing ourselves to become a sanctuary for God.

The portability of the tabernacle foreshadows the future movements of the Jewish people in exile, where they built synagogues and houses of study wherever they migrated. The tabernacle also stands as a symbol of the paradox of divine presence in the world: On the one hand, God is believed to be everywhere — or perhaps, as the Malbim argues, in human hearts — but on the other hand, the tabernacle (and later the Temple in Jerusalem and synagogues throughout the world) represents a physical location where humans can experience a connection to God.

The Tabernacle vs. the Temple

The Holy Temple in Jerusalem, first built in 957 BCE by King Solomon, became the permanent sanctuary for the Israelites to worship God (until it was destroyed and later rebuilt and destroyed again). The tabernacle was the portable sanctuary they used while wandering in the desert.

Archaeological Evidence of the Tabernacle

In 2013, it was reported that possible evidence had been found of the tabernacle in the ancient city of Shiloh, in the West Bank. Archaeologists discovered holes hewn into rock that may have been used for propping up the wooden beams of the tabernacle. Previous research at the site had also found remains of possibly sacrificed animals and evidence of bathing pools where the High Priest may have cleansed himself in preparation to enter the tabernacle.

Further Reading on the Tabernacle

The tabernacle is discussed at several points in My Jewish Learning’s Torah commentaries on the following weekly Torah portions: