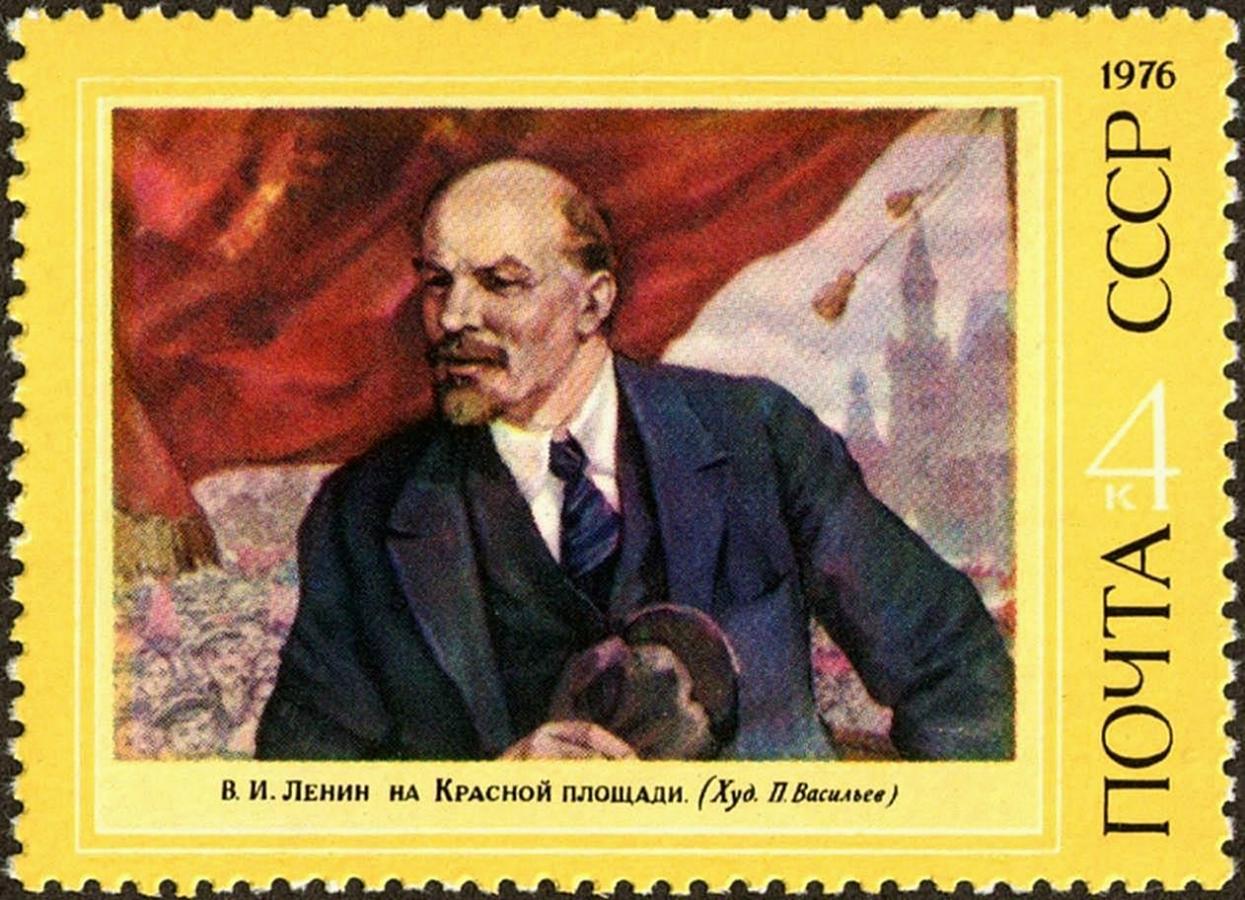

The Bolshevik Revolution undertook to change history. In line with that aim, its leaders set out to control the writing of history, including by controlling access to the archives that informed it. The scholar Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, who was born in the Soviet Union and studied there before coming to the United States, learned the hard way that history is shaped by how information is managed and made available. He believes that, when it comes to the Russian experience, Jews in particular have a large stake in the integrity of the history-writing process. Confronting the challenge head-on, he has published a book, Lenin’s Jewish Question, about the ancestry of the man who masterminded the 1917 Revolution and became the iron-fisted dictator of the early Soviet state.

A Jewish Great-Grandfather

The background is this. The declassification of documents since the collapse of the Soviet Communist tyranny in 1991 has brought irrefutable proof that Lenin’s maternal great-grandfather was a shtetl Jew named Moshko Blank. Whether or not Lenin himself was aware of this piece of information is uncertain, but by the time of his death in 1924 his sister had possession of the facts—and, by order of the Central Committee of the Communist party, was forced to keep them secret. The order held firm until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s.

How is a historian to approach this subject? For Petrovsky-Shtern, it is not simply a matter of exposing the truth, which others have already done. In writing his book, he was keenly aware of the way that, in today’s Russia, Jews continue to be blamed: by some, for Communism and its depredations by virtue of the fact that a number of prominent Bolsheviks were of Jewish origin; by others, for Communism’s collapse. He is especially worried about the former threat—i.e., the manipulation of truth by today’s anti-liberal nationalists bent on overestimating the Jewish role in the evils of Communism. In this book, he tries to set the record straight by proving that, in the key case of Lenin, there was nothing Jewish about the man.

One of his tools is genealogy. First of all, Moshko, the great-grandfather in question, converted to Russian Orthodoxy in 1844. He had already seen to the conversion of his sons a quarter-century earlier. Next, Moshko’s baptized son Alexander—i.e., Lenin’s grandfather—married a Christian woman of German descent. Finally, Maria, the daughter of this pair, who was clearly not a Jew by any reckoning, married the Russian Orthodox Ilya Ulianov. Thus, by the time we reach their son Vladimir Ilyich, we are four generations away from the original Jewish ancestor—himself, as we have seen, a convert to Christianity.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

An Internationalist

As for Vladimir Ilyich, he became a thoroughgoing internationalist, treating ethnic affiliations of all kinds as strictly temporary evils. Nor is anything to be made of his friendship and collaboration with Jews; behind all of Lenin’s alliances, as Petrovsky-Shtern documents, there lay only pragmatic calculation and ideology. “Once you join the Bolsheviks,” he writes, “you think class, not ethnicity. Moreover, when you join the RSDRP [Lenin’s party], you obliterate your ethnicity and become a class.” Genealogy by itself is frivolous that does not recognize the force of human decisions that determine historical fate.

But the duty of the historian does not stop there. As Petrovsky-Shtern’s title suggests, the question of Lenin’s Jewishness was intimately bound up, in the minds of Soviet rulers, with the “Jewish question” itself. The ranks of those rulers included ethnic Jews at the highest levels of the Communist party. Why did they insist on obscuring Lenin’s origins? Petrovsky-Shtern thinks it was because the party needed the image of a “pure” Russian founder. Indeed, the Russification of Lenin, the consummate internationalist, was part of a paradoxical process to de-internationalize Communism, and to refashion it as an ideology coterminous with Russian nationalism.

Curiously, Petrovsky-Shtern observes, those Communist ideologues of old have their counterpart in today’s Russian xenophobes, who cite the fact of a “Jewish” Lenin as further evidence for their thesis that Communism was an aberration in Russian history, a subversive and wholly alien implant with no roots in the pre-Communist Russian past. Thus does one deliberate distortion of historical reality beget its mirror image.

This study’s insistence on clear distinctions between historical truth and lies is most welcome, and makes a refreshing contrast with much Western scholarship that, in this area as in others, shows a greater interest in blurring boundaries than in achieving clarity. Yet, in striving to avoid ambiguity, Petrovsky-Shtern also inadvertently opens the very door he has tried to close. He has done so by making not Lenin but Moshko Blank into the most fully realized character in his book.

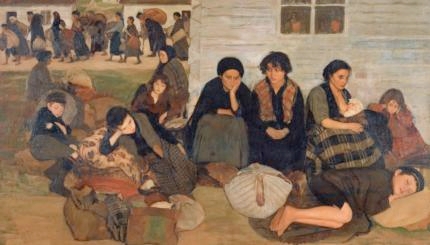

Moshko and His Neighbors

And what a character he was. Confined to Jewish small-town life, Moshko took out his resentments on his Jewish neighbors, who fought back by denouncing him to the Gentile authorities. In an intensifying spiral of recrimination, not only did Moshko denounce them in turn but, the records reveal, he became an informer against Judaism itself. We see him urging the Tsar to “reform” Russia’s Jews by fiat, and proposing measures for forcibly restricting the practice of the Jewish religion and moving the Jews toward Christianity.

This introduction to Moshko almost compels us, in short, to associate his behavior with the brutal, nation-wide suppressions that were among the landmark “achievements” of his great-grandson’s career. How, we can’t help wondering, might certain aspects of family history, among them the very denial of one’s identity and one’s God, have contributed to the violent, conspiratorial power-hunger and paranoia of one’s descendants?

To Petrovsky-Shtern, such speculation is illegitimate, an abrogation of the commitment to precision that is the hallmark of the historian’s discipline. In his way of thinking, Jewish converts, whether to Christianity or Communism, are no longer Jews, period, and they should be neither claimed nor charged as such. Yet even if one grants this in principle, there may still be much to learn from the often influential participation of former or ex-Jews in the development of modern anti-liberal movements. Instead of dwelling on the question of Jews and Communism, as many a scholar has done, might historians not do better to focus their attention on renegade Jews and Communism? There, as the Yiddish expression has it, may be where the dog lies buried.

Reprinted with permission from Jewish Ideas Daily