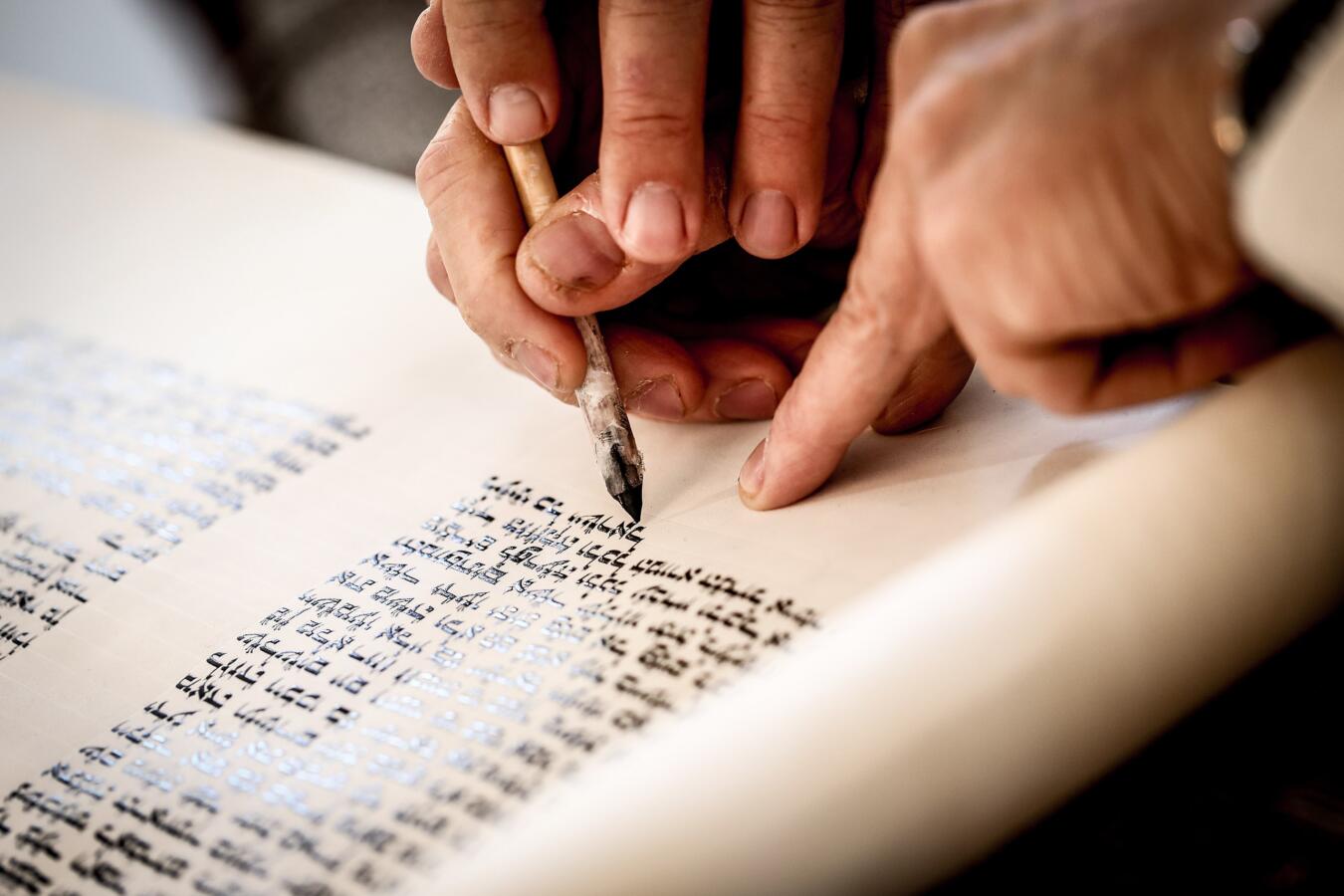

When most people think of Torah, they likely think of the Five Books of Moses (also known as the Pentateuch): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. These five books together form the first and most sacred third of the Jewish Bible, the Tanakh. In synagogues throughout the world, they are written in quill on a parchment scroll attached to wooden rollers (this scroll used for ritual purposes is called a sefer torah) and housed in the holy ark on the wall of the sanctuary that faces Jerusalem.

But the word “Torah” has many other meanings as well. It refers not just to the five books of Moses but also to all of Tanakh, and it sometimes is used to refer also to the Talmud and other rabbinic writings (known as the Oral Torah). Torah can also mean Jewish teachings writ large.

What is the difference between the Written Torah and the Oral Torah? Find out!

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

In ancient times, the word “torah” wasn’t a proper noun at all, or even necessarily a Jewish word — it was simply a Hebrew word that meant instruction and could refer to something as simple as a parent’s directive to a child.

For the purposes of this article, we will capitalize Torah when it refers to the Five Books of Moses, and leave it in lowercase when it does not designate those specific books and instead refers, for instance, to a specific instruction.

What the Word Torah Means

The Hebrew word torah literally means direction or instruction. The root, yod-resh-hey (ירה), originally likely meant to throw or shoot an arrow. The noun torah is rendered in a causative conjugation, which is just a way of saying that it literally means to cause something (or someone) to move straight and true. A torah is therefore something that directs, having connotations of offering strong and virtuous guidance.

Beyond instruction or teaching, torah can also mean law or statute — something one is not just guided to do, but required to do. And it can also refer to a custom, a kind of loose, unwritten law.

Both in antiquity and today, the word torah is used to refer to something quite small, such as a singular bit of instruction or teaching. Today, you might hear someone get up in front of a group to share “words of Torah” which could possibly have no direct relation to the Five Books of Moses. Equally, torah is used to refer to something much larger or more amorphous, even most or all of Jewish teaching and practice, old and new.

How the Five Books of Moses Came to be Called the Torah

The Torah itself, with a capital “T” (that is, the five books of Moses), does not actually refer to itself by name. In fact, it does not refer to itself at all, since these were originally separate books that were later gathered into a collection, traditionally in the time of Ezra. The word torah does appear throughout the five books where it clearly means “instruction.” For instance, in Exodus 24:12, it is essentially synonymous with mitzvah:

The Lord said to Moses, “Come up to me on the mountain and wait there, and I will give you the stone tablets with the teachings (torah) and commandments (mitzvah) which I have inscribed to instruct them.”

In a great many cases, torah refers to instructions that accompany a sacrifice or ritual. In these contexts, it is clear that it refers only to those specific instructions (to pick but one example, see Leviticus 7:11).

The Book of Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Torah, is different. This book, which is primarily composed of speeches of Moses, understands itself as a repetition of instructions that Moses received from God and gave to the Israelites. This book refers to its contents as torah, as teaching, right from the beginning:

These are the words that Moses addressed to all Israel on the other side of the Jordan … On the other side of the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses undertook to expound this teaching (torah).

Deuteronomy 1:1,5

Likewise, before presenting the Ten Commandments, Deuteronomy states: “This is the teaching (torah) that Moses set before the Israelites…” (Deuteronomy 4:44). In Deuteronomy, torah is not just law, but a written legal teaching. Both within Deuteronomy and elsewhere in the Bible, there are references to this law being written down and preserved. Moses inscribes the teachings he is imparting in stone (Deuteronomy 27:3) and makes a copy for the priests (Deuteronomy 31:9). Joshua later inscribes a copy of Moses’ teaching on stone for the Israelites’ benefit (Joshua 8:32).

Later biblical authors refer frequently to Torat Moshe, the teachings of Moses (see for example Joshua 8:31). In some cases, this may mean specifically Deuteronomy, for example in the story of King Josiah’s discovery of a long-lost scroll of the law (2 Kings 22:11). In other cases, it more likely refers to all five books of Moses (see Nehemiah 8:1).

It wasn’t until the post-biblical period that the five books of Moses, by then known as the “Torah of Moses,” became known simply as the Torah.

Torah as All of Jewish Tradition

This idea of Torah capaciously referring to the entire Jewish tradition is not new. In fact, the Talmud tells a humorous story that asks exactly where the boundaries of the term lie:

Rav Kahana entered and lay beneath Rav’s bed. He heard Rav chatting and laughing with his wife, and seeing to his needs.

Rav Kahana said to Rav: The mouth of Abba (i.e. Rav) is like one who has never eaten a cooked dish.

Rav said to him: Kahana, you are here? Leave, as this is unacceptable behavior!

Rav Kahana said to him: This is Torah, and I must learn.

Berakhot 62a

In this story, Rav Kahana sneaks into his teacher Rav’s bedroom and hides himself under the bed in order to observe Rav having intercourse with his wife. As if that isn’t enough of a boundary violation, he then calls out, while his teacher is in the midst of the act, and criticizes his teacher’s lovemaking! Rav, who reasonably thought he was sharing an intimate moment with his wife alone, is in disbelief: “Kahana, are you here? Leave!” But Rav Kahana is not only completely unembarrassed, he has a sassy retort: “This is Torah, and I must learn.”

The Talmud gives Rav Kahana the last word, but most of us would side with Rav. It leaves us to wonder: Is this too Torah? Just how far do the boundaries of this life-giving, sustaining, sacred, all-consuming text extend?