A nazir is a person who has vowed to consecrate themselves to God for a period of time, abstaining from all intoxicants and, indeed, any grape products at all; hair cutting; and incurring ritual impurity by coming near a corpse, even if the body is one of their close relatives — a restriction not even placed on priests, who are also barred from corpse impurity but are allowed to bury close relatives nonetheless. Such a vow is known as a nazirite vow and can be taken by both men and women. The word nazir itself means “separate,” (and in reflexive conjugations it means “abstain”), but in modern Hebrew it is the word used for “monk.”

The rules for a nazirite vow are outlined in Numbers 6:1–21. This includes not only the rules for a nazir, but the procedure for ending the nazirite period. There is also an entire tractate of the Talmud, known as Tractate Nazir, which discusses the rules and procedures of the nazirite vow and Maimonides devotes an entire section of the Mishneh Torah to the topic.

At the conclusion of the nazirite period, a nazir is required to bring a number of offerings to God, after which his hair is shaved at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting (or, in later times, the Temple). Among the offerings specified in Numbers is a sin offering, normally brought in atonement for wrongdoing. This has led some to speculate that adopting a nazirite vow is considered sinful, perhaps because such a person has denied themselves certain worldly pleasures that are normally allowed and thereby has caused the body to suffer. This view is recorded in the Talmud, which goes further in saying that if it is sinful merely to deny oneself wine, then it is certainly sinful to afflict oneself through fasting and other acts of self-mortification.

At the same time, the Bible is clear that a nazir is “holy to God,” which would imply that being a nazir is a good thing. The Talmud relates a story of a man with beautiful hair who elected to become a nazir after seeing his reflection in water and felt pride well up in him as a result. His period of abstention was concluded with the compulsory shaving of those coveted locks. The man’s actions were celebrated as a gesture to counter excessive pride in his appearance.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

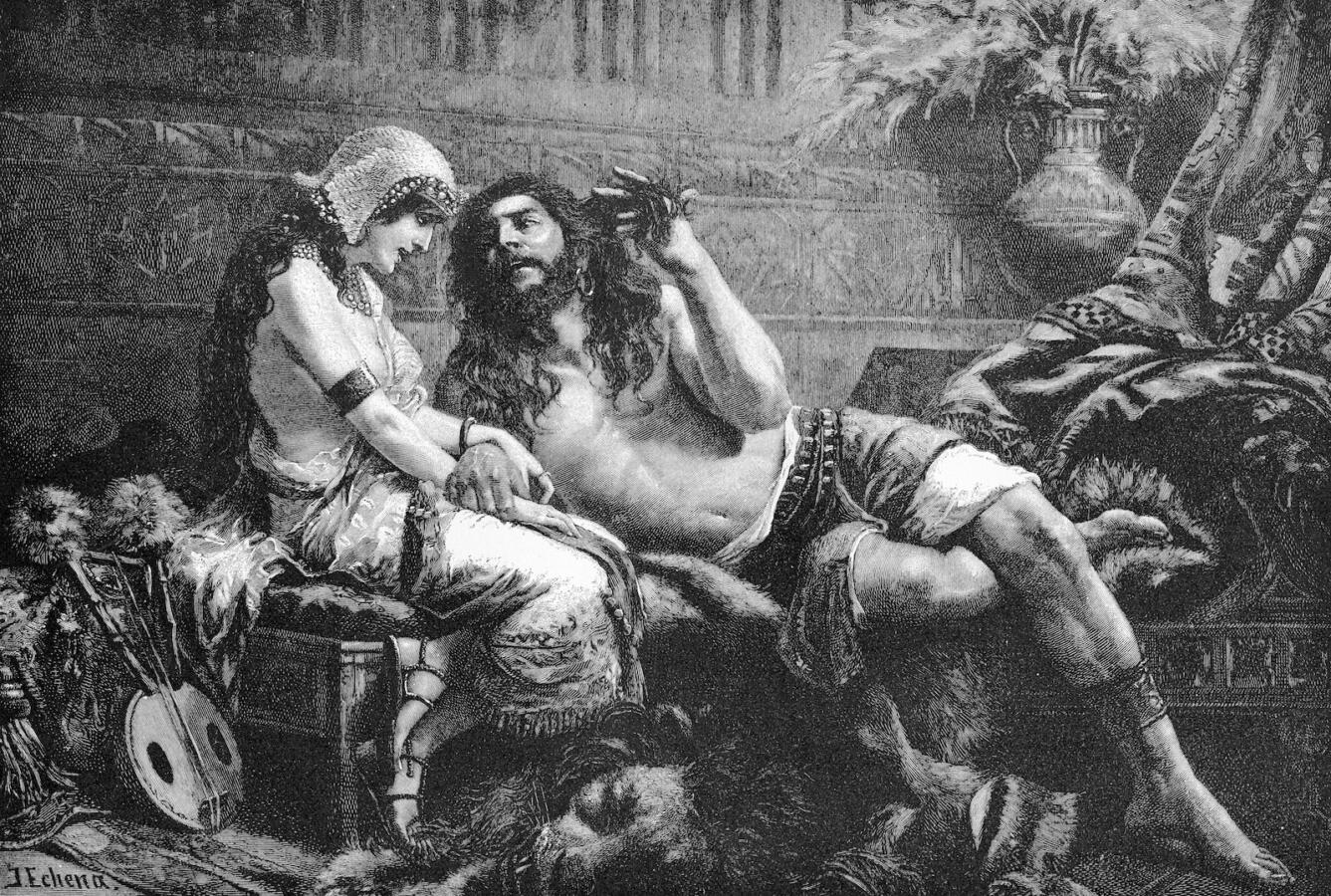

The two most famous nazirites in Jewish history are Samson, who claimed his long nazirite hair was the source of his strength (legendarily shorn by Delilah), and the prophet Samuel, whose nazirite vow was made on his behalf by his mother Hannah, who promised God that if she were granted a child she would consecrate him as a nazir (1 Samuel 1:11).

Today, the nazirite vow is virtually unheard of — but not entirely so. Perhaps the most famous nazir in modern times was Rabbi David Cohen (1887-1972), who came to be known as harav hanazir, the rabbi nazir. A mystic and student of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first chief rabbi of pre-state Israel, Cohen took his vow as a young man, abstaining throughout his life from cutting his hair and consuming wine. Because there is no Temple today, and no way to bring the concluding nazirite sacrifices, someone who takes a nazirite vow today does so for life.