In preparation for God’s appearance on Mount Sinai, Moses and the Israelite people “stood at the foot of the mountain” Exodus 19:17 waiting to see and to hear what transpires.

The unusual preposition — be-tachtit (“at the foot of”) — is understood in the Midrash to mean that the Jewish people were literally standing under the mountain. That is, at the moment God speaks the Ten Commandments, God also uproots Mount Sinai from the ground and holds it over the people, as if to say, “If you accept the Torah, fine; if not, here shall be your grave.” Avodah Zarah 2b The implication is that the Jewish people accepted Torah only through coercion.

The description of the ensuing events only reinforces that interpretation. The thunder, lightning, and thick clouds that accompany God’s presence on Mount Sinai terrify the people Exodus 20:14 and they beg Moses to be their intercessor.

Many Jewish communities will commemorate this moment during the holiday of Shavuot. The event is often referred to as z’man matan torateinu (“the time of the giving of our Torah”) and some celebrate its anniversary by staying up all night in study. But given both the biblical and rabbinic understanding of that moment, we may well wonder about the celebration of a “gift” both forced and fear-inducing.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Another Shavuot custom may provide some insight: the recitation of the Book of Ruth, which many communities read on the second day of the holiday.

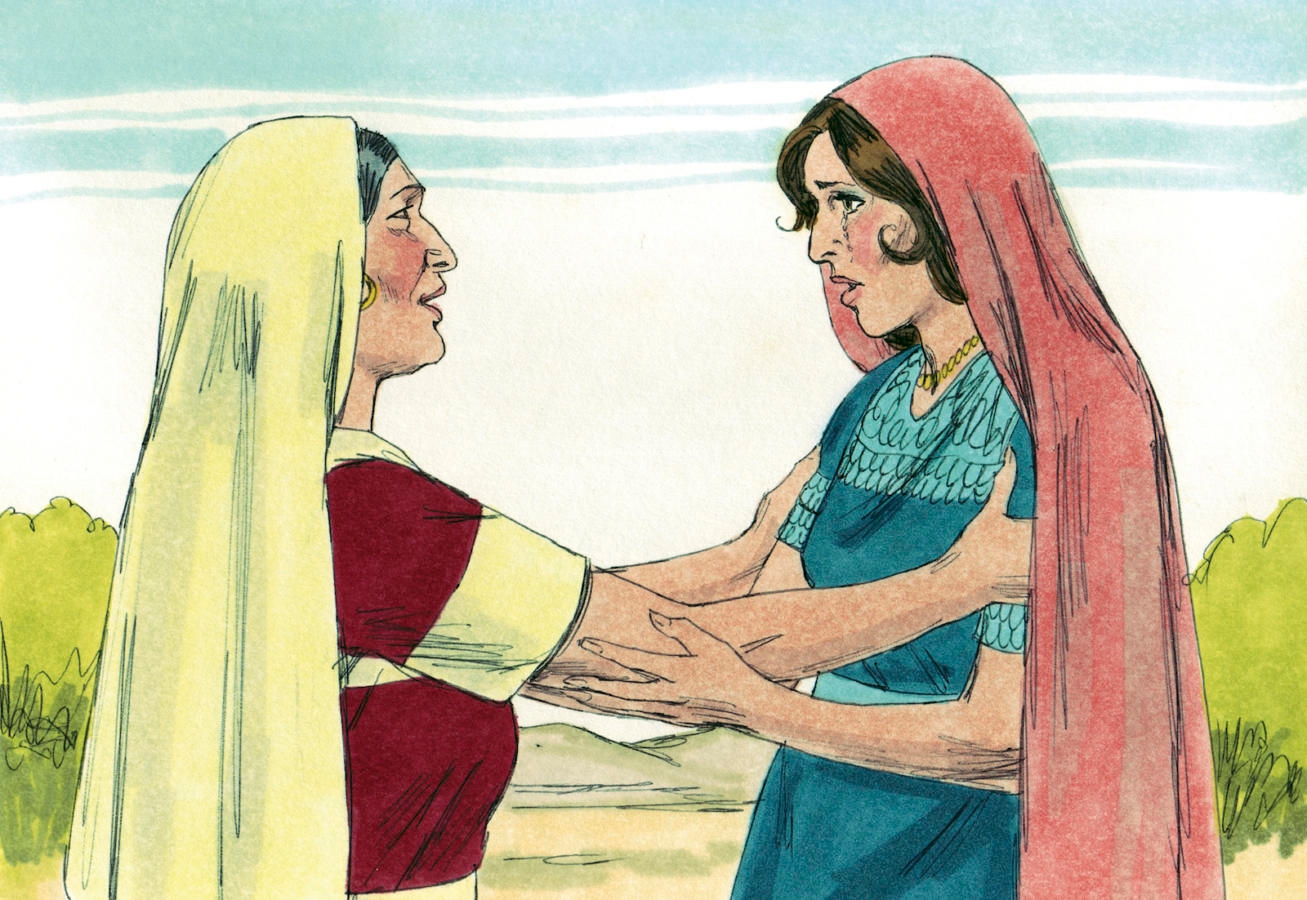

The short story revolves around the deep relationship between the heroine and her Bethlehemite mother-in-law, Naomi, forged after the death of the latter’s husband and two sons. As she journeys back home, Naomi urges her daughter-in-law to stay in her native Moab, but Ruth refuses, speaking these iconic words: “For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God, my God” Ruth 1:16.

These words can be read in dialogue with the story in Exodus. They certainly show no less commitment than the joint affirmation of the Israelites at Sinai: “All that the Lord has spoken we will do, and obey.” Exodus 24:7. Indeed, Ruth’s declaration is understood as evidence of her taking the covenant upon herself. In the rabbinic imagination, she becomes the prototypical convert. Just as the Jewish people all gathered together at the mountain in the desert in the presence of the God of Israel, so too does Ruth cling to Naomi on the road in Moab, invoking the God of Israel.

But the contexts are very different. The animating value in the book of Ruth is chesed (lovingkindness) and loyalty that surpass the simple duty implied in the Israelites’ dispassionate response of na’aseh v’nishma (“we will do and obey”). After all, Ruth’s pledge to Naomi ends with the ultimate vow: “Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried” Ruth 1:17. Later in the book, Naomi returns her daughter-in-law’s care and concern, the wealthy landowner Boaz shows kindness and generosity to both women, and all three find joy in the birth of Obed.

Even God is different. In Exodus, God is a loud, physical force that moves mountains. In the book of Ruth, God is the quiet but inexorable activity that moves the characters from emptiness to fulfillment.

It is perhaps for this reason that there is a practice of saying Ruth’s words each morning when laying tefillin, her credo of devotion and faithfulness recited as the boxes are placed between the eyes and on the arm — literally taking the words of Torah upon oneself. The ritual conjures the image of Ruth speaking to Naomi as they journey, each having lost her husband, two women cleaving to each other in hope for a better future together. It is an act of making oneself a partner in God’s ongoing work in the world.

Ruth’s relationship to Naomi and to Torah can be a model for our own orientation to the celebration of Shavuot. In Exodus, the Israelites experience an overwhelming display of power and might that leaves them shaking in fear and desiring to distance themselves from what may emerge from those clouds around the mountain. In the book of Ruth, she — no less in the dark — bravely and wholeheartedly faces what may come down the road.

Shavuot is called “the time of the giving of the Torah” rather than “the time of the receiving of the Torah.” The sages point out that the giving took place on one day to one people, but the receiving takes place at all times and in all generations.

As we celebrate the giving of the Torah on Shavuot, may we may act each day with the love and intimacy modeled by Ruth in the receiving of Torah.

Midrash

Pronounced: MIDD-rash, Origin: Hebrew, the process of interpretation by which the rabbis filled in “gaps” found in the Torah.