Prayer is hard for American Jews. Studies bear this out. Even as the percentage of Americans attending worship declines, Jews attend much less regularly than other religious groups. Even those Jews who affiliate with a synagogue pray less frequently than churchgoers.

Why don’t Jews like to pray?

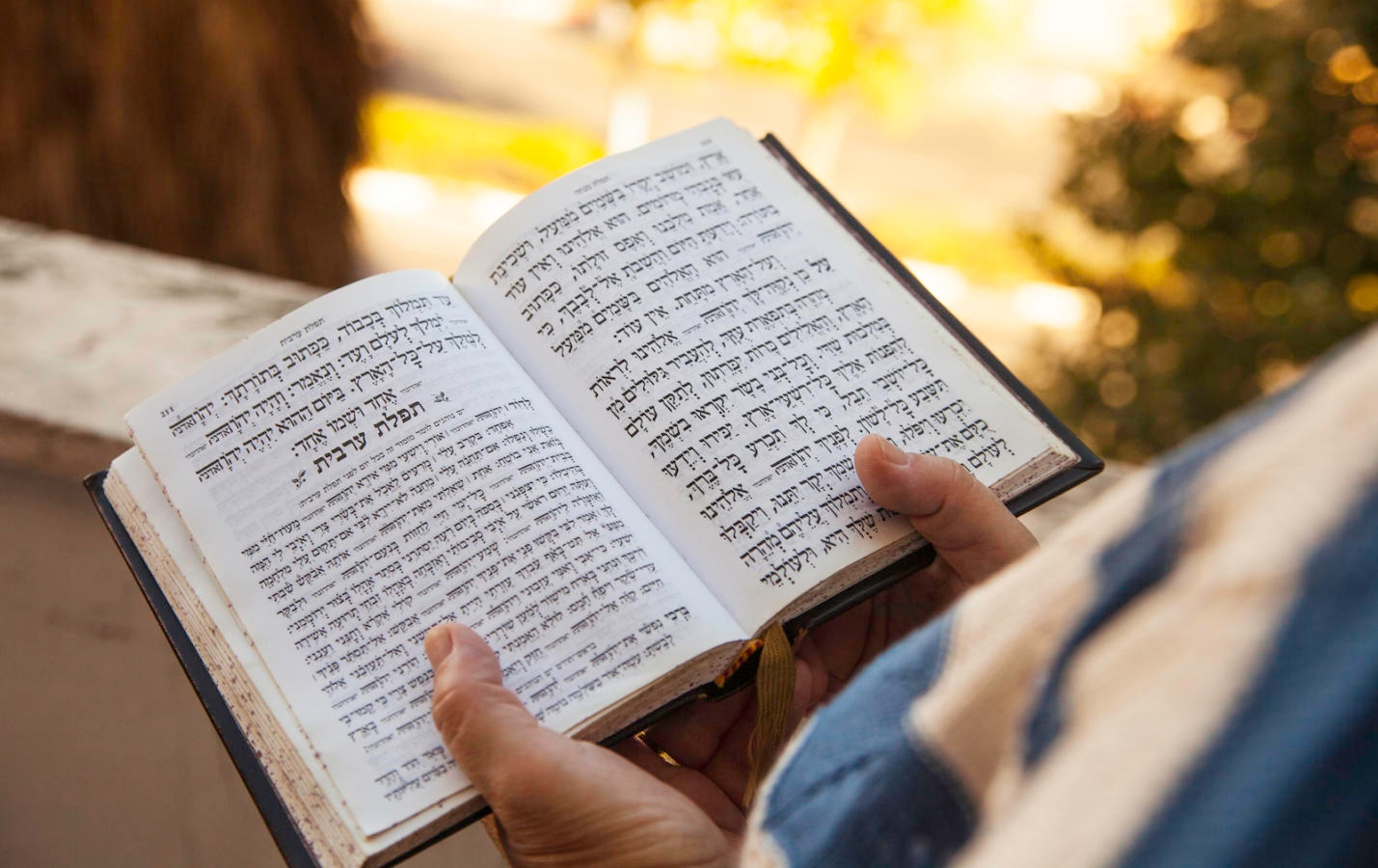

Part of the reason is language. Most American Jews do not know Hebrew, and worship can feel intimidating. Why say words we do not understand?

But those who understand the words of prayer face a deeper challenge. Why say words we do not believe? And why say those words to a God one doubts is listening? In other words, the challenge for prayer is more theological than linguistic. Many American Jews feel this tension. I hear it from them all the time.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

Sometimes when people ask me why they should pray with words they do not believe, I simply tell them that prayer is good for you. Empirical science proves the point. People who attend worship regularly live, on average, seven years longer than those who do not.

For some people, that’s enough. But others push back. Attending synagogue is one thing, praying is another. Why not come to synagogue for a class or a social action project?

That’s when I turn to the two words that define the purpose of prayer for me: trust and humility. The Hebrew equivalents are emunah and anivut

Emunah is often translated as faith. But faith in English implies ascribing to a certain set of beliefs. That is not what emunah implies. Rather, it suggests faithfulness or trust. It is commitment to a principle or an idea. The word amen is derived from emunah, and it often means simply, “I agree!”

So when we pray, we say we trust in the underlying ideals of the words we are saying. We are trusting that life has meaning, that we can find wisdom in Torah, that observing Shabbat can bring peace and perspective.

Anivut is a requisite to this kind of trust. Humility is not meekness or intellectual laziness. It is not believing something just because the book tells us to. Rather, humility is seeing ourselves from a higher perspective. It is seeing our life against a wider canvas.

As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks puts it, “False humility is the pretense that one is small. True humility is the consciousness of standing in the presence of greatness … it is a form of perception, a language in which the ‘I’ is silent so that I can hear the ‘Thou’, the unspoken call beneath human speech, the Divine whisper within all that moves. Humility is what opens us to the world.”

In prayer, humility means acknowledging that we do not know all the answers. We need the wisdom of those who came before. They knew things we do not. A humble posture is not one where we turn off our brains. Rather, we open them up to the perspectives of those who wrote the prayers and looked at the word with awe and wonder.

One of the people who looked at the world in this way is the writer S.Y. Agnon. An observant Jew, he wrote the official prayer of the state of Israel. He also won the Noble Prize for Literature in 1966. Shortly after he was notified of the award, he greeted reporters at his home. They asked him to sit and write at his desk so they could get an appropriate picture for the newspaper. He sat and his desk and scribbled something on a piece of paper. When all the reporters left, someone looked at the desk and the paper he scribbled on.

The Nobel Prize winner had written five words taken from one of the most magnificent Jewish prayers, Unetanah Tokef, one of the emotional high points of the Rosh Hashanah liturgy. What were those words?

Adam yisodo me’afar, visofo le’afar. “Our origin is dust and our end is dust.”

A prayer of humility had penetrated his soul.

Rabbi Evan Moffic is the author of “First the Jews: Combatting the World’s Longest Running Hate Campaign” and blogs at www.rabbimoffic.com