Reprinted with permission of the author from The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays.

There is an important model in the holiday of : how to speak of God today. A process of profound secularization has occurred in recent centuries. The growth of a scientific mindset, of the sense of natural law, and the tendency to reductionism that denies all transcendence has made the use of religious language problematic.

Some would deny the possibility of religious experience. But this is cultural imperialism that makes absolute a certain literal cast of mind and seeks to deny any alternative models of reality. Such arrogant secular claims are increasingly disputed by sophisticated philosophers.

After the Holocaust, one must challenge the absolute claims of a secular culture that created the matrix out of which such a catastrophe could grow. It is all the more urgent to bridle runaway secularism in light of the warning that comes to us out of the concentration camp universe. That world constituted an attempt at a total kingdom of man where God was excluded and humans assigned themselves the role of God. The result was the devil’s work: total degradation and hell.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

One way to check the excesses of secularization is to continue speaking in the same old way, i.e., the language of human helplessness and easy miracle. The resurgence of fundamentalism in the world is, in part, a dialectical corrective to the abuses of secularism. However, using premodern language means being out of place in this civilization; it almost suggests that the can flourish only in certain limited cultures. So the question remains: How can a Jew speak of God today?

Other problems deepen the question. The rise of pluralism in an open society has created a sense of embarrassment and loss of credibility with the language of absolute demand. How can one speak of the absolute in such a setting? The rise of affluence and hedonism has created a new ethic and search for expression in pleasure. Yet many of the classic religious models are focused on denial, control, and restriction of pleasure. How can one express religious values in the pleasures of the body?

Then there is the excruciatingly intense problem of theodicy–the problem of evil–which looms larger than ever because of the monstrous evils inflicted in this time. In The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan dramatically underscores the difficulty of speaking of God after an innocent child has been brutalized and torn to death by dogs. Then what shall be spoken in a generation when thousands went by dogs and by fire, when over a million innocent children were savagely killed? No statement, theological or otherwise, should be made that would not be credible in the presence of burning children. Any easy affirmation of God would appear to mock the burning children. Any easy denial of God would appear to turn the children’s deaths into a gigantic travesty. A simple denial of God would appear to deny the reality of redemption in our time and the validation of biblical promise by contemporary fulfillment.

How then can one speak of God with integrity?

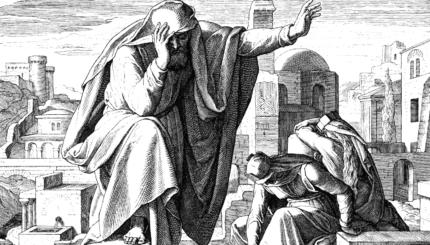

The holiday of Purim is a good guide as to how one can affirm. The answer is: humorously, tentatively, humanistically. Purim teaches how to speak subtly, admitting the alternatives yet knowing the reality of meaningfulness. Purim speaks of "chance" (lots), yet hiding between forms of chance is the Divine Presence. Vashti’s recalcitrance enabled Esther to assume the throne; the king’s insomnia raised Mordecai to greatness. These are "random" incidents that, decoded, spell out a pattern of redemption. These are natural events that point beyond themselves to a greater meaning.

Such speech about God also torments, of course. What kind of world is this, where a king authorizes mass murder and, a short time later, does not even remember the incident! When Esther tells him of the Jews’ tragic fate, he asks her: Who is this who has dared to do this? What kind of world is this, where genocide is narrowly averted by flirty tea parties, by currying favor and appealing to male chauvinism? Yet by that margin the Jews are saved. The promise endures. The people of Israel live. One recognizes the implication: Our Father still lives.

No wonder Purim speaks in the language of party, feast, and drinking. Celebrate the vulnerability of life. Eat, drink, and be merry, for today the good win! Tomorrow the turn of the wheel may endanger it all. Do not despair or sulk! Admit your vulnerability and share your wealth with the poor, your friends, your family. In this way, pleasure expresses religious value. The material embodies the spiritual hope and affirmation.