In 1965, as part of the Vatican II council, the Catholic Church published a long-anticipated declaration entitled Nostra Aetate, offering a new approach to the question of Jewish responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus. The document argued that modern-day Jews could not be held accountable for Jesus’ crucifixion and that not all Jews alive at the time of the crucifixion were guilty of the crime. This was a remarkable step forward in the history of Christian attitudes toward Jews, as Jewish blame for Jesus’ death has long been a linchpin of Christian anti-Semitism.

Nevertheless, many Jews were disappointed. They had hoped that the Church might say that the Jews had in fact played no role in Jesus’ death.

Jews Lacked A Motive for Killing Jesus

Indeed, according to most historians, it would be more logical to blame the Romans for Jesus’ death. Crucifixion was a customary punishment among Romans, not Jews. At the time of Jesus’ death, the Romans were imposing a harsh and brutal occupation on the Land of Israel, and the Jews were occasionally unruly. The Romans would have had reason to want to silence Jesus, who had been called by some of his followers “King of the Jews,” and was known as a Jewish upstart miracle worker.

Jews, on the other hand, lacked a motive for killing Jesus. The different factions of the Jewish community at the time — Pharisees, Sadducees, Essenes, and others — had many disagreements with one another, but that did not lead any of the groups to arrange the execution of the other allegedly heretical groups’ leaders. It is therefore unlikely they would have targeted Jesus.

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

READ: The Land of Israel Under Roman Rule

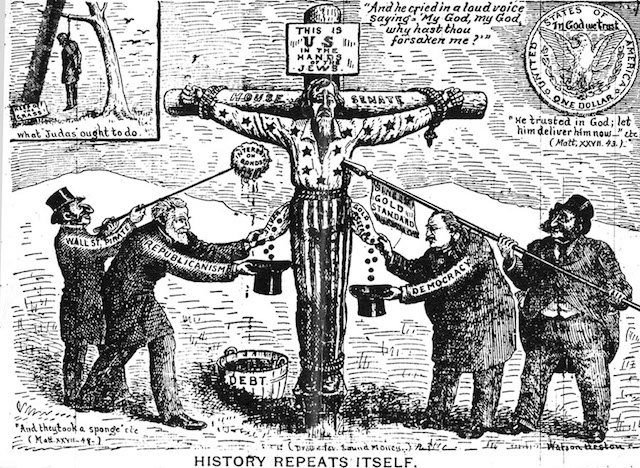

But the belief that Jews killed Jesus has been found in Christian foundational literature from the earliest days of the Jesus movement, and would not be easily abandoned just because of historians’ arguments.

The New Testament Account

In the letters of Paul, which are regarded by historians to be the oldest works of the New Testament (written 10 to 20 years after Jesus’ death), Paul mentions, almost in passing, “the Jews who killed the Lord, Jesus” (I Thessalonians 2:14-15). While probably not central to Paul’s understanding of Jesus’ life and death, the idea that the Jews bear primary responsibility for the death of Jesus figures more prominently in the four gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which have slightly different accounts of Jesus’ life.

Matthew, the best-known gospel, describes the unfair trial of Jesus arranged and presided over by the Jewish high priest who scours the land to find anybody who would testify against Jesus. Eventually, the high priest concludes that Jesus is guilty of blasphemy and asks the Jewish council what the penalty should be. “They answered, ‘He deserves death.’ Then they spat in his face and struck him” (Matthew 26:57-68). Matthew’s description of Jesus’ suffering and death on the cross (referred to by Christians as Jesus’ “passion”) has becomes the basis for many books, plays, and musical compositions over the years, and is prominent in Christian liturgy, particularly for Easter.

All four gospels suggest either implicitly or explicitly that because the Jews were not allowed to punish other Jews who were guilty of blasphemy, they had to prevail on the reluctant Romans to kill Jesus. Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, is described as basically sympathetic to Jesus but unable to withstand the pressure from the Jews who demanded Jesus’ execution. This idea is expressed most clearly in the gospel of John: “Pilate said, ‘Take him yourselves and judge him according to your own law.’ The Jews replied, ‘We are not permitted to put anyone to death'” (18:31).

In the most controversial verse in all the passion narratives, the assembled members of the Jewish community tell Pilate, “His blood be on us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25). This is the source for the Christian belief that later generations of Jews are also guilty of deicide, the crime of killing God.

Church Fathers and Thereafter

In the writings of the Church Fathers, the authoritative Christian theologians after the New Testament period, this accusation appears with even more clarity and force. One of the Church Fathers, Justin Martyr (middle of the second century), explains to his Jewish interlocutor why the Jews have suffered exile and the destruction of their Temple: these “tribulations were justly imposed on you since you have murdered the Just One” (Dialogue with Trypho, chapter 16).

READ: Jewish-Christian Relations in the Early Centuries

Throughout classical and medieval times this theme is found in Christian literature and drama. For example, in a 12th-century religious drama, entitled “The Mystery of Adam,” the biblical King Solomon addresses the Jews, prophesying that they will eventually kill the son of God. Here is a rhyming English translation from the original Norman French and Latin:

This saying shall be verified

When God’s own Son for us hath died

The masters of the law [i.e. the Pharisees or rabbis] ’twill be

That slay him most unlawfully;

Against all justice, all belief,

They’ll crucify Him, like a thief.

But they will lose their lordly seat,

Who envy him, and all entreat.

Low down they’ll come from a great height,

Well may they mourn their mournful plight.

(Translation from Frank Talmage’s Disputation and Dialogue)

Even into modern times, passion plays — large outdoor theatrical productions that portray the end of Jesus’ life, often with a cast of hundreds — have continued to perpetuate this idea.

In the Talmud

Interestingly, the idea that the Jews killed Jesus is also found in Jewish religious literature. In tractate Sanhedrin of the Babylonian Talmud, on folio 43a, a beraita (a teaching from before the year 200 C.E.) asserts that Jesus was put to death by a Jewish court for the crimes of sorcery and sedition. (In standard texts of the from Eastern Europe — or in American texts that simply copied from them — there is a blank space towards the bottom of that folio, because the potentially offensive text was removed. The censorship may have been internal — for self-protection — or it may have been imposed on the Jews by the Christian authorities. In many new editions of the Talmud this passage has been restored.) The Talmud’s claim there that the event took place on the eve of Passover is consistent with the chronology in the gospel of John. In the talmudic account, the Romans played no role in his death.

In Jewish folk literature, such as the popular scurrilous Jewish biography of Jesus, Toledot Yeshu (which may be as old as the fourth century), responsibility for the death of Jesus is also assigned to the Jews. It is likely that until at least the 19th century, Jews in Christian Europe believed that their ancestors had killed Jesus.

From the first to the 19th centuries, the level of tension between Jews and Christians was such that both groups found the claim that the Jews killed Jesus to be believable. Thankfully, in our world it is heard less frequently. But we should not be surprised if it persists among people who take the stories of the New Testament (or of the Talmud) as reliable historical sources.

To read this article, “Who Killed Jesus?” in Spanish (leer en español), click here.