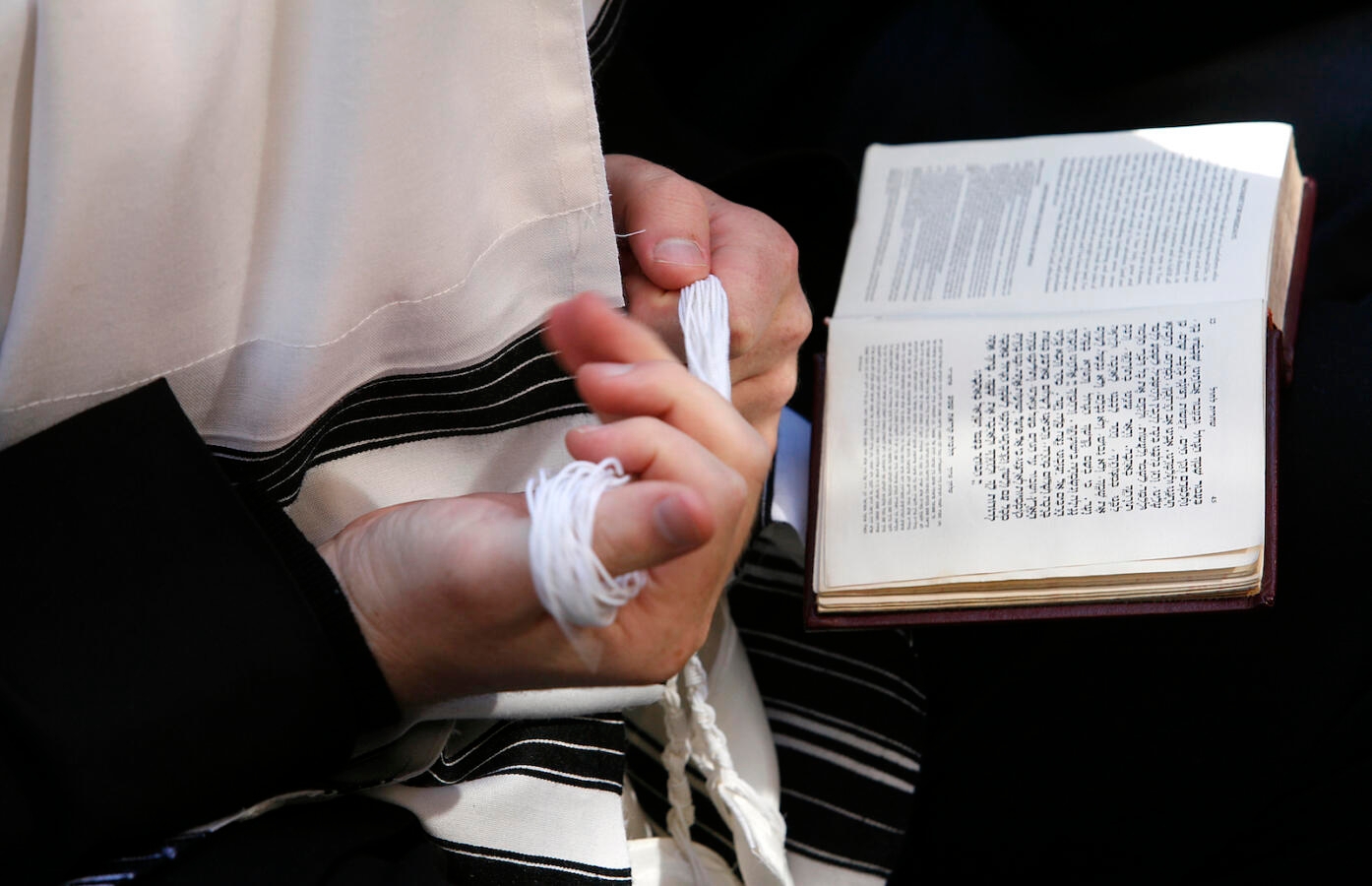

When I admit I don’t pray and rarely attend synagogue services, I’m often met with wide-eyed surprise. After all, I’m a rabbi; I should be going to shul.

Jews I know who don’t go to shul often excuse themselves by saying they don’t know Hebrew and can’t follow the service, or that they’re not made to feel welcome, or that they can’t afford synagogue dues — but these are shallow excuses.

If you want to learn Hebrew and understand the liturgy, there is no dearth of rabbis, cantors and Jewish educators eager to teach you. If you want to feel welcomed, make yourself welcoming. Introduce yourself, and you will find people happy to engage with you. As for the cost of synagogue membership, no synagogue has a pay-to-pray policy.

I suspect the real reason people don’t go to shul is that they prefer to do something else. If they wanted to attend synagogue services, they would. They don’t, so they won’t.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

Occasionally, I find myself in thoughtful conversation with Jews who enjoy Jewish communal worship and attend synagogue regularly. When I admit I do neither, they immediately make two assumptions about me. Either they assume I’m an atheist and try to convince me that I don’t have to believe in God to pray. Or they assume I’m a literalist and proceed to argue that prayer is poetry and hence open to whatever interpretation I wish to impose upon it.

On the first claim, it’s true: You don’t have to believe in God to pray, but why would you pray to God if you don’t believe in God? This would be like phoning my dad when I know he is dead. Yes, I can do it, but there is no real value in it.

More importantly, I’m not an atheist. An atheist believes God is a figment of the human imagination. I’m a panentheist. I experience God as the impersonal happening of all reality. I experience everything (pan) as a manifesting of God (theos) in God (en). For me, God doesn’t exist — God is existence itself.

Or as the late Chabad leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, put it:

The absolute reality of God, while extending beyond the conceptual borders of “existence,” also fills the entire expanse of existence as we know it. There is no space possible for any other existences or realities we may identify — the objects in our physical universe, the metaphysical truths we contemplate, our very selves … do not exist in their reality; they exist only as an extension of divine energy.

The God I experience is the God another hasidic master, Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky, called chiut, or aliveness. I don’t pray to chiut. I awaken in, with and as chiut.

On the second point, I agree that prayer is poetry, but poetry isn’t an empty vessel into which I can pour any meaning I desire. Ask poets who spend hours searching for the right word to express the meaning they seek to convey. Yet, even if it were true that I could impose whatever meaning I wish on the prayers, spending 90 minutes or more pretending not to say what I am clearly saying isn’t prayer. It is an exhausting editing process that prevents me from experiencing anything other than my own cleverness. Again, this is not something I find meaningful, and hence another reason why I do not attend communal Jewish worship.

This is not a critique of Jewish worship or criticism of those who find meaning in it. It is simply an explanation of why I, as one God-intoxicated Jew, don’t find a home in conventional Jewish worship. I may be unique, but I doubt it. I suspect there are many Jews like me.

So what might draw me, and perhaps others like me, back to shul on Shabbat morning? Here’s one suggestion.

Regarding prayer, I stand with the psalmist, who wrote: “silence is praise” (Psalm 65:2). Yet it is wise to ease into silence with a nigun, a wordless melody, allowing the melody to slowly lead us into a repetition of the Shema, the core Jewish prayer attesting to the oneness of divine existence. We might then begin to lengthen the pause between recitations, the growing silence eventually replacing the recitation itself. As it does, we may come to detect what the Torah in Genesis calls m’rakhefet, the “vibrating” of the Divine in all reality. A quiet nigun might then bring us out of the silence.

This might then be followed by a group study of some Torah text, a walk outdoors, a moment of silence to remember the dead we are mourning that week, or a light lunch. The particulars are less important than providing space for those of us who don’t believe in a God who hears our prayers, and who are reluctant to recite liturgy that suggests precisely that, to still gather in Jewish community to experience together the divine energy vibrating though every facet of creation.

This article initially appeared in My Jewish Learning’s Shabbat newsletter Recharge on Dec. 3, 2022. To sign up to receive Recharge each week in your inbox, click here.