We tend to think of Tisha B’Av, the fast day that commemorates the destruction of both ancient temples, as a time of mourning. But the traditional observances of Tisha B’Av — fasting, being unable to sit anywhere except on the ground, not washing, abstaining from sexual activity, not greeting other people, not wearing fresh clothes for the whole week before — are closer to the experience of being a refugee than to being a mourner.

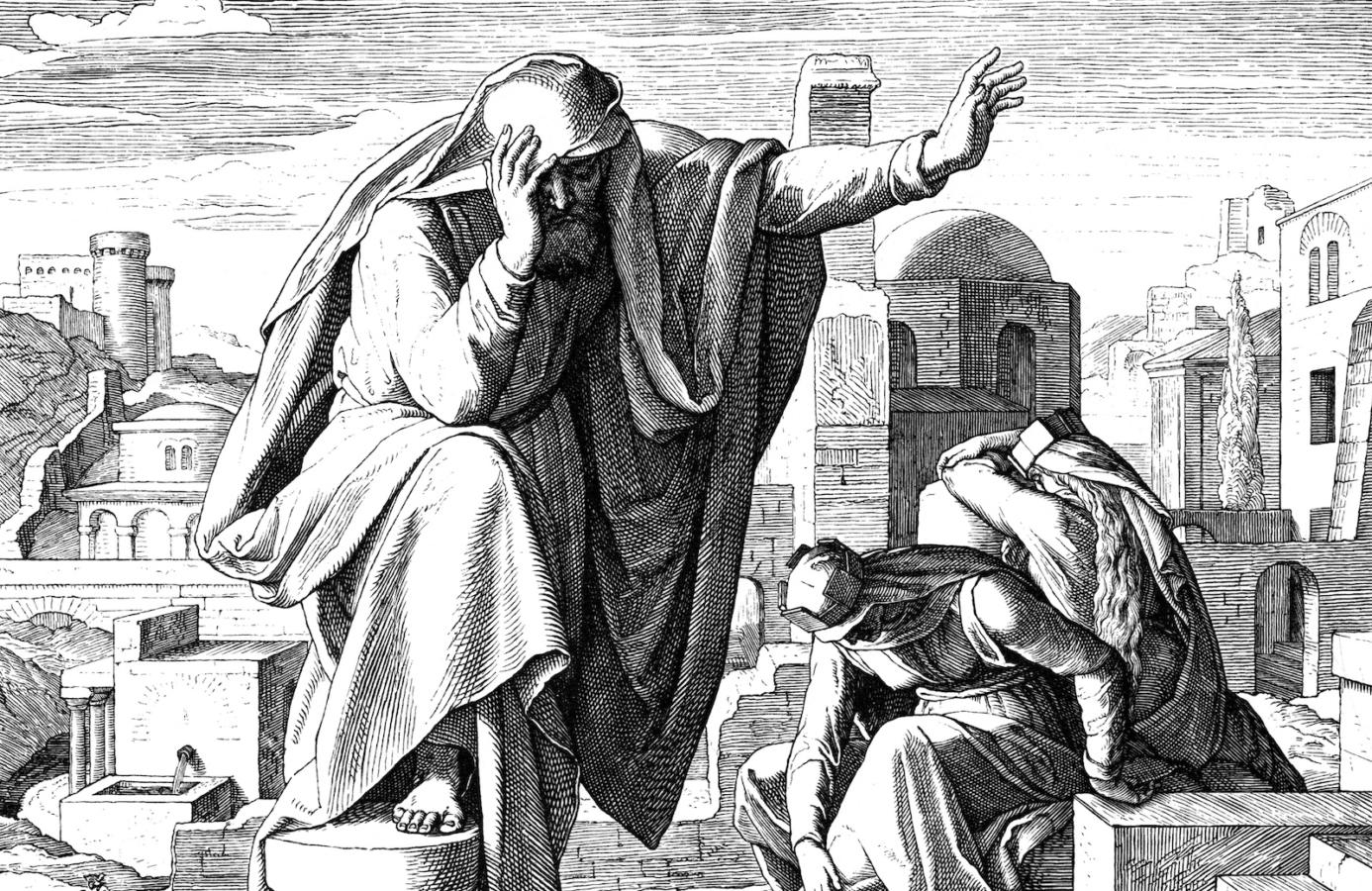

When the Temple was destroyed, the people were thrown into exile. Jerusalem became a war zone and its people became refugees, forced to risk their lives to escape violence, famine, and devastation. The suffering was tremendous — “like deer, not finding a place to graze, walking without strength before a pursuer,” in the words of the Book of Lamentations.

The author(s) of Lamentations (Eicha in Hebrew), the biblical text traditionally read on Tisha B’Av, believed that what happened to the Jewish people was the result of divine judgment. But even though the book sounds like it’s about God punishing us, it’s not really a theodicy — that is, a justification of God’s actions. The question our ancestors faced was not whether the disaster could be reconciled with God’s goodness. Rather, the question was whether God still cared about them.

Choosing a God that cared enough to punish them was better than choosing a God that didn’t care at all. But the anxiety that maybe God doesn’t care is also woven throughout Eicha. In every chapter, the poet beseeches God to pay attention Lamentations 1:9 Lamentations 2:20, and in the very last verse, the poet wonders if God has rejected us forever.

With your help, My Jewish Learning can provide endless opportunities for learning, connection and discovery.

This idea that exile and homelessness were punishment for our sins seems alien to many modern Jews. But the ancients were not as far from us as we think. In Eicha itself, most of the chapters describe the punishment God inflicted as excessive and abusive. Only in chapter 3 is Zion’s destruction consistently described as fair and just.

The real perspective of Eicha is summed up in verse 2:13: “What can I compare to you, daughter Jerusalem, that I may comfort you?” What images, what words, will help people bear the memory of tragedy? The poet is willing to say anything that will enable the people to find meaning and hope in the face of exile.

There is another way to understand the destruction of Jerusalem and the dispersion of its people. According to the prophet Jeremiah, the traditional author of Eicha, the reason for the Babylonian exile was that the people did not let the land rest every seven years, as is biblically mandated Chronicles II 36:21. Since 490 years had passed without a sabbatical year, Israel had to go into exile for 70 years — one year for each sabbatical that was missed.

The Torah teaches that God will take the side of the land against the people if forced to, and that the land will “enjoy her Sabbaths” Leviticus 26:34 — even if that means the people are exiled or wiped out. What has intrinsic value is not humanity, but humanity’s potential to do justice.

The Torah outlines six curses for not observing the sabbatical year, which describe how the relationship between the people and the land unravels. Two curses involve children being eaten – by wild animals Leviticus 26:22, then by their own parents Leviticus 26:29. That image is repeated in Eicha — Lamentations 2:20, 4:10 — and it is the main connection between Eicha and Leviticus. But the idea that the destruction of Jerusalem came about because of how the Jewish people treated the land is not found in Eicha, where identification of the land with the people is total. Instead, Jerusalem’s downfall results only from the moral downfall in relationships between human beings.

In Jeremiah too, the fate of Jerusalem is sealed only after the rich, who briefly set their slaves free, re-enslave them when it looks like the danger has passed Jeremiah 34. The overall message of these texts is that how we treat the stranger (the refugee, the foreigner, the convert) and the poor determines whether we have the right to remain in the land.

Even though most people are uncomfortable with the idea of divine retribution, in an age when our ecological “sins” are coming home to roost, the connection between disaster and divine retribution is not so farfetched. And since Creation is also compared to the sacred Temple in the Midrash, it is natural to connect the story of the Temple’s destruction with the destruction of the earth and the sixth mass extinction initiated by human action.

But there is a very big difference: When the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed, there were other lands for the refugees to flee to. If we destroy the Temple that is the Earth, there will be no place untouched by tragedy.

As climate change puts more pressure on our ecosystems and our social systems, more and more people will become refugees like our ancestors, forced to flee areas no longer capable of sustaining human habitation. And for those fortunate enough not to live in such places, we will need all the spiritual resources we can muster to stay open to the humanity of the refugee and the stranger, while also taking care of our own communities.

All of these issues can become intertwined with the experience of Eicha and the story of Jerusalem’s destruction. Reading Eicha is an invitation to remember what it means to be a refugee, and to think about how we can move towards justice for all people, for all species, and for the land herself.

All translations are taken from Eikhah/Laments, Rabbi David Seidenberg’s original translation of the Book of Lamentations. Laments is designed to connect the reader on the most visceral level to the text and also includes more discussion. Laments can be downloaded here.