One of the ongoing gags in the film Zoolander is the premise that the main character is unable to turn left. Hilarious. But difficulties with left turns are no joke (at least not in places where you drive on the right side of the road). According to a U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration study, left turns were the critical pre-crash event in 22.2% of accidents, about 20 times as often as right turns. Perhaps that’s why UPS has its drivers avoid unnecessary left turns, which have been called “the most dangerous directional change a driver will ever attempt.”

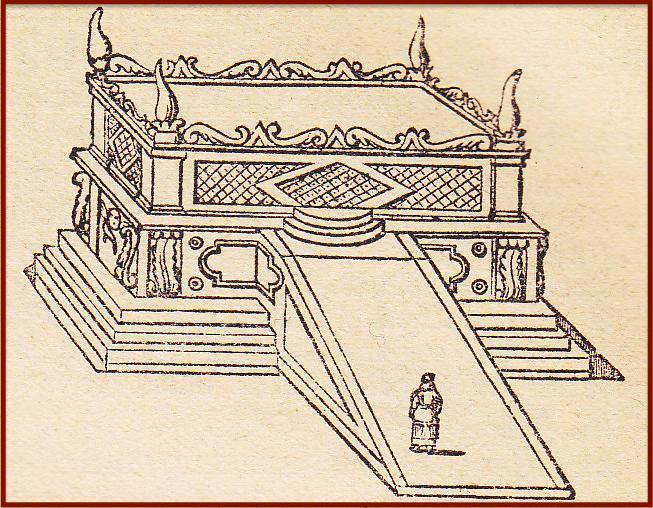

But even before the advent of the automobile, left turns were suspect. Today we’re in the middle of a section of Yoma that deals with how and where to sprinkle sacrificial blood on the large altar that stood in the Temple courtyard. Picture an elevated, square-shaped platform with raised “horns” on each corner and a red crimson line running around the perimeter. The flat top of the altar had a roaring fire where some sacrifices were burned. Sacrificial blood was applied, by various methods, to the sides (above and below the crimson line), corners, horns or other parts of the altar — all depending on the type of sacrifice.

19th century engraving that imagines what the Temple altar might have looked like (via Wikimedia Commons).

On our page today, the rabbis discuss sacrifices that need to have blood sprinkled on all four sides (north, south, east and west) of the altar. This is accomplished by approaching two diagonally opposite corners, northeast and southwest, and making sure to hit all four sides in the process. In some cases, the priest will efficiently flick his wrist at a corner and cover two sides of the altar with blood in one motion. In other cases, it would take two motions to sprinkle the blood on both sides. With two significant corners of the altar to sprinkle, the northeast and the southwest, the rabbis need to know: Which corner comes first?

Help us keep Jewish knowledge accessible to millions of people around the world.

Your donation to My Jewish Learning fuels endless journeys of Jewish discovery. With your help, My Jewish Learning can continue to provide nonstop opportunities for learning, connection and growth.

What does it matter if he sprinkles first on the northeast corner of the altar and then on the southwest corner? Let him sprinkle first on the southwest corner and then on the northeast corner!

It is because the master said: All turns should be only to the right, to the east, sprinkling that which he encounters first.

What does this mean? Imagine you are a priest approaching the altar from the south, with the aim of sprinkling blood on both the southwest and northeast corners. Heading first to the southwest corner would require turning left, a big no-no. Consequently, the priest is supposed to veer to the right and then work his way around the altar counterclockwise, sprinkling at the first of the two designated corners he encounters — the northeast corner.

This idea of turning only to the right in making ritual offerings isn’t limited to our page. We see similar takes in Tractates Sotah and Zevachim as well. And the sentiment extends beyond Temple settings. Commenting on our page 200 years ago, Rabbi Eliezer Papo noted the preference for the right side in a slew of other contexts as well: the right shoe goes on before the left one, the right arm goes into its shirtsleeve before the left one, a tallit should be wrapped over one’s shoulders from the right side, and for handwashing, the right hand should first use a utensil to pour water over the left. “In all matters,” he says, “one must be very strict about giving honor and priority to the right side.”

A take we saw back on Shabbat 88b echoes here:

And that is what Rava said: To those who are right-handed in their approach to Torah, and engage in its study with strength, good will, and sanctity, Torah is a drug of life, and to those who are left-handed in their approach to Torah, it is a drug of death.

Ouch! Lest we think that this left-phobia is just Jewish tradition (or even superstition) or modern motor safety concerns, preferences for the right linger in English as well. The word “dexterous,” with its positive denotations and connotations, comes from the Latin dexter, meaning “right,” while “sinister” derives from Latin sinister, or “left.” These vestiges of preference for the right have stayed with us over the centuries, even if they’re just below the surface.

So as we move through this discussion, let’s take a moment to give lefties a hand. Today’s page, and life in general, throws a lot at them, and the least we can do is acknowledge everything they have to put up with.

Read all of Yoma 15 on Sefaria.

This piece originally appeared in a My Jewish Learning Daf Yomi email newsletter sent on April 26th, 2021. If you are interested in receiving the newsletter, sign up here.