At my small all-girls’ high school, I was encouraged to speak my mind, to spark controversy, and engage in civil discourse.

That was the thought behind an assignment my junior year of high school. We were told to write a piece that someone would find offensive, and the teacher handed us a sample paper a student had written a few years prior. As my eyes skimmed the three-page essay, I soon realized that this was not just meant to spark controversy. The essay was a call to end the Warren Feig Holocaust Memorial Lecture—the annual forty-five-minute assembly dedicated to the Holocaust—and replace it with a lecture on some other genocide because the Holocaust was no longer relevant.

The essay’s antisemitic undertone held the question, “Why are we still talking about the Holocaust?” To this student, the question was rhetorical, implying that we shouldn’t be. Growing up in a household with the Israeli Declaration of Independence hung on the wall and a strong sense of Jewish identity instilled in me from my days of Jewish preschool, I found the fact this question was even being discussed inside the classroom not only offensive but ignorant.

Maybe even more unsettling was that many of my Jewish peers—who, like myself, have family who was either murdered by the Nazis or escaped them—agreed with this opinion. Trying to argue with my classmates about this topic was difficult because there were (and are) other genocides where millions of people have been murdered. I had to argue the importance of remembering the Holocaust without being accused of implying that it’s the only holocaust we should be remembering, which was shockingly more difficult than I would have presumed.

I was living in one of the most liberal, accepting cities on the globe, and I had scarcely experienced blatant antisemitism. Even the strongest critics of Israel who surrounded me at school wouldn’t try to argue (to my face) that the Holocaust hadn’t happened or that Hitler did nothing wrong.

Having something to say without knowing how to phrase it became stressful and emotionally taxing. My instinct to just ignore Holocaust remembrance was equally as depressing. My school’s environment was encouraging me to stir the pot, but ostensibly the students were scarcely willing to engage in civil discourse. I began to perceive my school as a place for homogenous opinions, and anything that strayed from what the majority believed would be ridiculed. Regarding a topic as sensitive as the Holocaust, especially as a Jew who had family murdered, I began alienating myself from discussions to avoid attempting to explain how I felt during particular conversations.

As diverse as my high school is, it is still not very Jewish. I hadn’t known many Jews outside of New York, and I couldn’t have predicted what was to come when I boarded an overcrowded chartered El Al flight to Poland on March 19th.

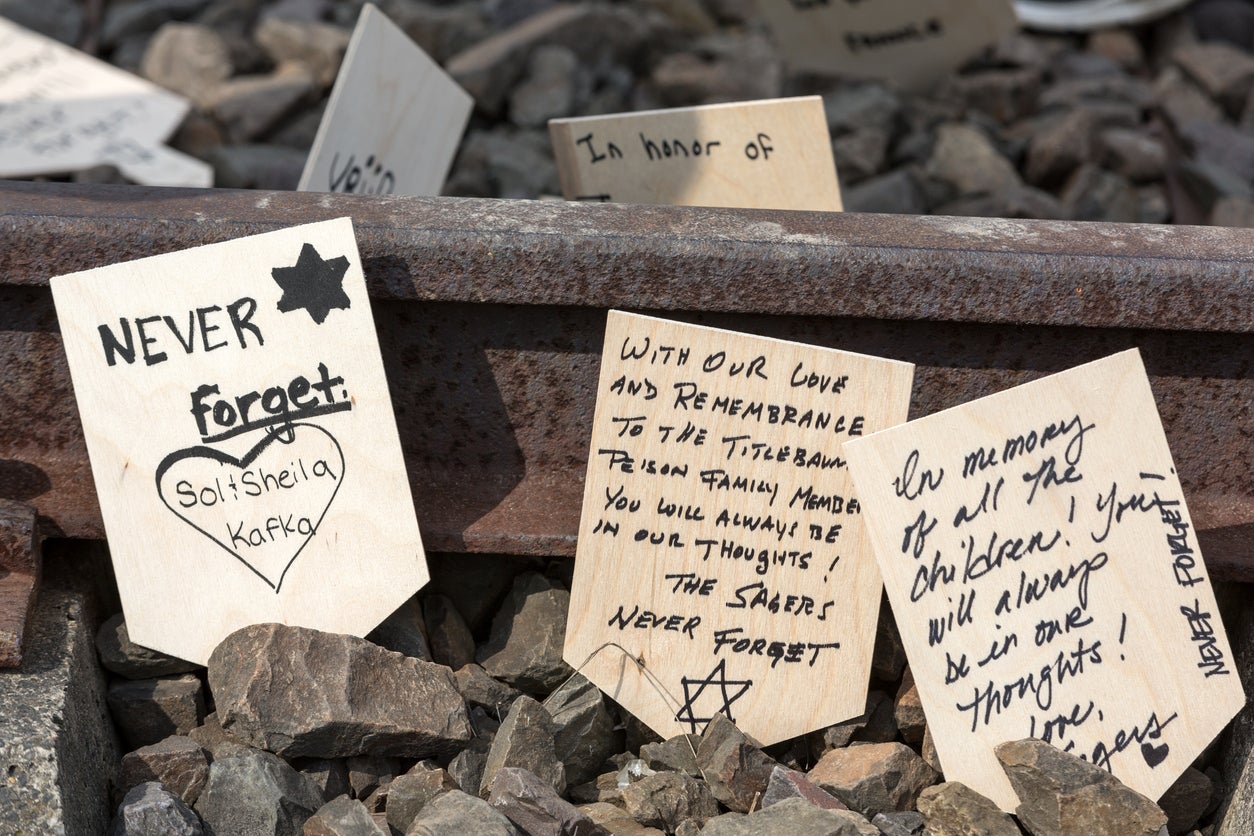

I stood in the middle of Birkenau with nearly 20,000 Jews. I was marching with Jews from all corners from the world alongside our survivors. I looked in front of me and then behind me. In either direction, I could not see the ending point. It seemed, for the first time in my life, I was totally surrounded by people who share the same vision as I do, who have everlasting, unconditional love and understanding of Israel and Judaism. While it’s impossible for 20,000 to hold exactly the same opinions, we all saw the piles of hair and shoes at Auschwitz, we all sang Hatikvah in cattle cars, and we all understood to keep teaching and never forget. At that moment, the ignorance of my classmates seemed unimportant. It seemed that all my frustration, anger, disappointment, and confusion melted away. There was a never-ending sea of Jews who understood and felt as I did. Reflecting back on this experience, however, I realize that although I may feel more at ease to speak my mind and engage my ignorant classmates in a discussion, I should never forget how I felt in those moments of difficulty.

Leaving these 20,000 Jews, whether I had individually met them or just celebrated in the streets of Jerusalem with them, had put me in a state of melancholy. It was difficult when no one would understand certain parts of my humor that my March friends had found hilarious. At first, I was more frustrated than I had been before I left because I found what I had been missing. Shortly after this initial stage of sadness, however, I felt empowered to take a new perspective.

Recalling the survivors’ stories and breaking down in tears overlooking the Dome of Ashes, I could not allow myself to stay silent for any longer. I had to combine my feelings of security and frustration to engage my classmates in conversation and challenge their opinions of Holocaust remembrance. Although it would be nice to feel comfortable in every classroom setting, I learned to overcome the initial feeling to withdraw myself from a conversation. I may not have been able to find the right words to say before, but eventually, I found the right way to speak from a place of experience and emotions. After all, life would be boring if I were always surrounded by like-minded people, and March of the Living helped me realize how strength can lie in differences as well as numbers.